How Highlands poverty created the blueprint for the NHS

- Published

For 70 years the NHS has provided a "cradle to grave" health service throughout the UK, but many of its principles were forged in Scotland more than three decades earlier.

The story began in 1911 with the establishment of the National Insurance (NI) scheme, a system of health insurance and forerunner of the welfare state.

Flora Ferguson, the first nurse in the Highlands to be given a motorbike by HIMS to help bring medical services to remote areas

It was based on contributions from employers, the government and workers themselves.

But in the crofting counties of Scotland it did not cover most people, who were not formally employed, so had no employer to pay a contribution.

Levels of poverty in the north of Scotland were high and health provision was patchy, says Colin Waller, retired archivist at the Highland Archive in Inverness.

"Many parishes were struggling to actually keep doctors. Assynt, for example, had five doctors in seven years up to 1910," he said.

"Diets were poor. Up to 25% of deaths were not certified, where the family had not been able to call a doctor because they couldn't afford one.

"When you think the cost for a doctor's call-out was something in the region of £2-£3 when actual monetary income for a year was around £20-£30."

The solution was the Highlands and Islands Medical Service (HIMS), a unique social experiment set up after the Dewar Committee report of 1912, which had shocked the government.

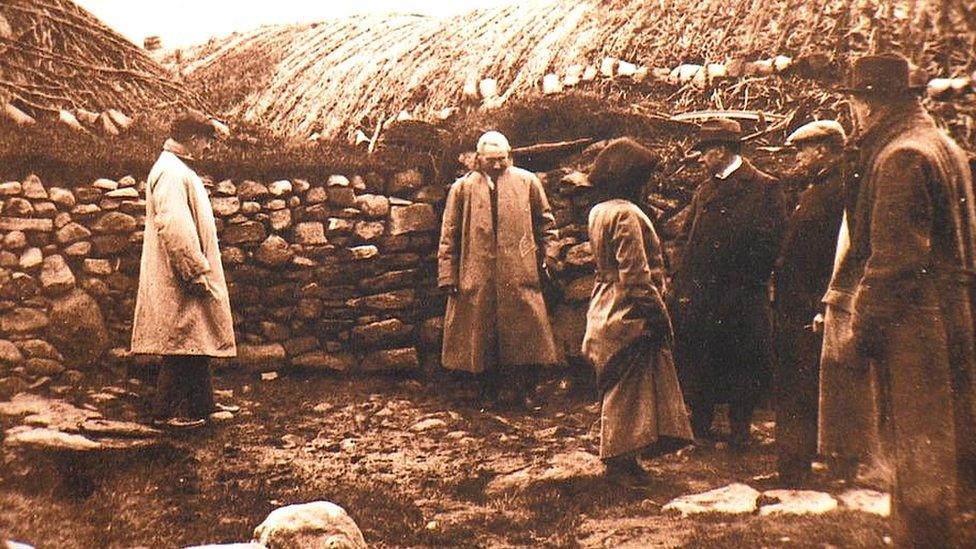

The Dewar Committee took evidence of living conditions and health care across the Highlands and Islands

Mr Waller said the report, which had gathered evidence from across the north, had been designed to shock.

"It completely destroyed the idyllic myth of the Highlands as being thatched cottages with peat smoke rising, chickens in the yard, hay ricks," he said.

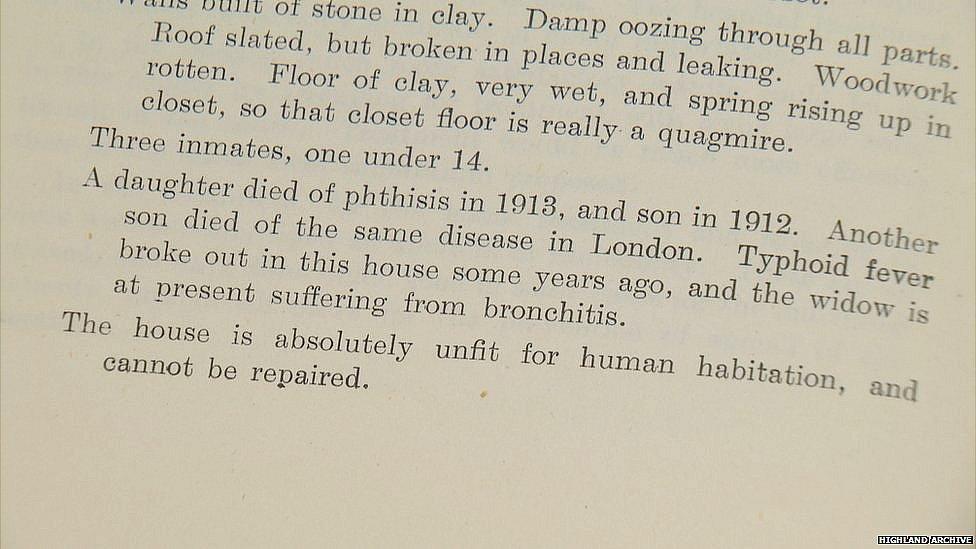

The Dewar Committee report highlighted shocking living conditions

"It showed the Highlands for what they really were: poor living conditions, poor housing and diet.

"A complete lack of doctors on the ground, lack of nurses even, an acute shortage of hospital provision."

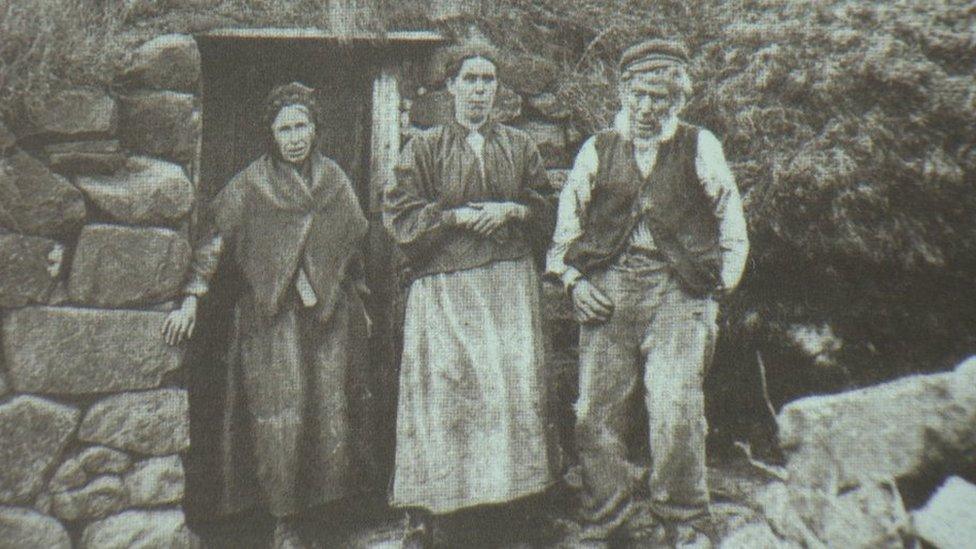

Highland houses where families and animals lived together were blamed for the spread of TB

The report highlighted concerns about a lack of preventive care and widespread tuberculosis (TB) caused by unhealthy black houses in which whole families lived in one room with a turf roof, no windows and often with animals housed at one end.

St Kilda nurse

Many in the north were unable to afford a GP's fee of between £2-£3, about a tenth of their annual income.

HIMS, which received Treasury funding of £42,000 a year - approximately equal to £4.5m today - provided a guaranteed minimum salary for GPs, who were then able to charge lower fees to patients, a maximum of 5/- (25p) irrespective of the distance covered.

Doctors were paid mileage for their cars and, later, houses were provided for them, and nurses equipped with motorbikes.

World War One delayed the introduction of the service, although a resident nurse was found for the island of St Kilda in 1914.

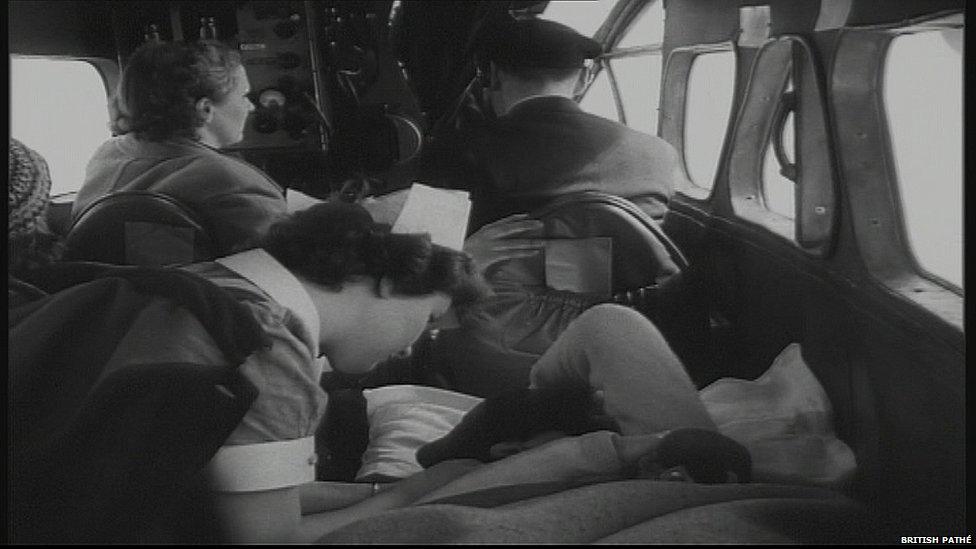

By 1948, Scotland's pioneering air ambulance service was carrying 275 passengers a year from remote locations

HIMS continued to develop, with an air ambulance service operating from 1935.

It had aircraft based at Renfrew Airport, bringing patients from the islands for emergency treatment in Glasgow.

By 1948 it was carrying 275 patients a year, the service paid for by HIMS and local councils.

A review of HIMS in 1936 - the Cathcart Committee - concluded it had been "an outstanding success" which was "universally approved".

The report said: "On the basis of the family doctor, there has been built up by flexible central administration a system of co-operative effort, embracing the central department, private general practitioners, nursing associations, voluntary hospitals, specialists, local authorities and others, to meet the medical needs of the people."

Dr Jacqueline Jenkinson, senior lecturer in history at Stirling University, said: "It was probably the most detailed investigation into health in Britain at the time.

"And they recommended a unified health service. But they thought it would be under local authority control.

"That's not what actually happened with the NHS, but that's what they recommended at the time with the GP at the heart of it."

Model for others

Even before the NHS was set up in 1948, the influence of HIMS was being felt as a model for health care in remote areas across the world.

The American nursing pioneer Mary Breckinridge visited Scotland in 1924 and on her return established the Frontier Nursing Service in Kentucky on the HIMS model.

She wrote: "The combination of doctor and nurse is extraordinarily impressive.

"Many of the doctors say that practice in their areas would be impossible without the services of the nurses, and everywhere we are told that co-operation between doctor and nurse leaves nothing to be desired."

Similar programmes have also been established in New Zealand and Canada.

HIMS revolutionised care for more than 300,000 people on half the land mass of Scotland.

Unlike other local medical schemes, it was directly funded by the state and administered centrally by the Scottish Office in Edinburgh working with local committees.

By 1948, HIMS had been providing comprehensive care for 300,000 people for 35 years, something the rest of Britain was about to experience.