Russell and Blackford: the SNP's good cop, bad cop?

- Published

MPs and MSPs have been debating Holyrood's powers and the devolution settlement

Same topic, different day - and the tone markedly less aggressive than in the parallel Westminster exchanges.

Which is not, in practice, setting the bar high. Or low. Or...OK you get the concept. I refer to the Mundell Mauling by Ian Blackford, the SNP's leader in the Commons.

Mr Blackford feels genuinely aggrieved with regard to the row over post Brexit powers in devolved areas, 24 of which Westminster wants to retain for up to seven years.

Further, he was undoubtedly goaded by sedentary and horizontal comments from Scots Tory MPs, one of whom appeared unaware that the SNP had campaigned for a Yes/Yes vote in the 1997 referendum.

Further, he sensed a vulnerability on the UK government benches. They know, they really know, that they messed up big time when they ended up only allowing 19 minutes for the Commons debate on Scottish powers - with each of those minutes taken up by the Cabinet Office minister David Lidington.

Still, Mr Blackford's attack on the Scottish Secretary David Mundell was quite something to witness. As Mr Mundell sat glumly silent, Mr Blackford roared at him to get up and defend Scotland. When Mr Mundell eventually rose, it was to say that the Blackford comments were unworthy of retort.

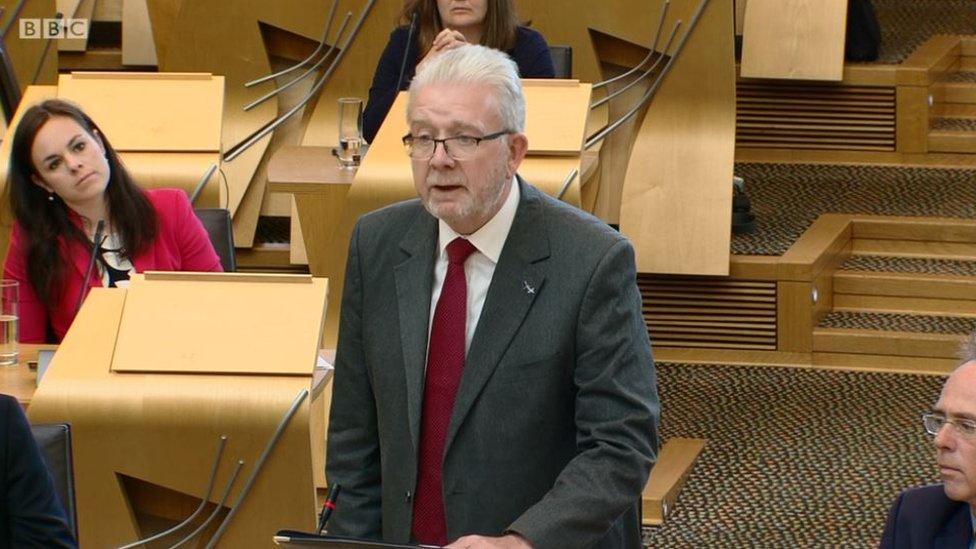

Today at Holyrood Mike Russell, the Minister for Mitigating Brexit, was more constrained - although equally acerbic on the stance adopted by the Tories, both in Westminster and Holyrood.

Was this bad cop, good cop? Was it, in short, a planned strategy? Think not, on balance. It seems to me more likely that Mr Blackford's anger and frustration spilled over in the confrontational atmosphere of an evening debate in the Commons.

Ian Blackford boiled over during Monday's debate on devolution

To be clear, Mr Russell did not miss. He said Westminster was "archaic", that it ignored Scotland on an institutional basis, that the Tories were guilty of "insularity and arrogance".

And he broadened the attack, warning that the "defence mechanism" of the Sewel convention was now being overturned by the UK government, notably Mr Mundell in his comments last Thursday to the effect that it was "implicit" in Sewel that the UK might have to act in the absence of agreement with Holyrood.

Mr Russell demanded that the provisions of Sewel must now be placed on a statutory footing. Something, do not forget, which was attempted previously only for the UK Supreme Court to remind us all that Westminster remains sovereign - and that a convention is just that.

International rescue

But there were emollient touches too. He remained open to talks with the Davids, Lidington and Mundell. He would meet other parties.

Prompted by Patrick Harvie, he was even moved to agree that the Scottish government might welcome international arbitration to resolve the dispute with Westminster.

To be clear, Mr Russell also acknowledged that it was unlikely the UK government would acquiesce in this suggestion. He's right. UK sources ridicule the idea.

Mike Russell updated MSPs on the Brexit row on Tuesday

We have here alternative interpretations of Sewel or, perhaps more precisely, of the power balance between Holyrood and Westminster.

Sewel provides that the UK government and parliament will not "normally" seek to legislate in devolved areas without the express consent of the devolved legislature involved.

That was, in itself, an effort to square the circle. Those who formed the cross-party convention which devised the devolution plan wanted to entrench the powers of Holyrood, to protect it from Westminster depredation.

At the same time, they recognised that Westminster remains a sovereign parliament. As I recollect, that endorsement of sovereignty was one of the red lines insisted upon by Tony Blair when he backed Donald Dewar in difficult discussions within his first cabinet.

Badly handled

Hence Sewel. Hence that word "normally". Hence, also, a system which has worked without breach in the near twenty years of devolution. Hence the row now that there is a breach, with Westminster voting for provisions which have been opposed not just by the SNP but by every party at Holyrood, except the Tories.

That breach, say Mike Russell and Ian Blackford and others, is a disgrace, an abomination, a democratic outrage.

Tories dissent. They accept privately that the matter has been miserably badly handled. But they say that the UK government could not back down on this when the objective was to offer what degree of certainty might be thought feasible to UK farmers and traders.

Scottish ministers insist that the problem could have been resolved by an inter-governmental agreement.

Adam Tomkins questioned whether these were "normal" times

Which is where one arrives at the fundamental point. UK ministers say, in effect, that they cannot rely upon such an agreement, particularly with Northern Ireland. In practice, they are saying that they must have power over matters which affect the whole UK. They alone, albeit in consultation.

Scottish ministers dissent from that. They say Scotland was told it was a partner in the UK. Now it has been reduced, again, to a part. Hence Mike Russell's talk of groundhog day.

There is another element which Adam Tomkins for the Scots Tories put rather better than his counterparts at Westminster.

Were these, he asked, "normal" times? He suggested that the Scottish minister had argued to the contrary when he was seeking Holyrood support for the continuity bill, designed to replicate provisions of the EU Withdrawal Bill.

There is another point which is perhaps too arcane to advance in turbulent debate. Is the EU Withdrawal Bill legislating in devolved areas such as farming - or is it rather coping with the consequences of a development in a reserved issue, relations with the European Union?

I have seen hints of that argument in UK papers. It probably influences the advice given to the Holyrood presiding officer that the continuity bill is ultra vires in that it presumes that a future consequence, with regard to devolved matters, has already happened.

Again, to be clear, the Scottish government dissents very strongly from this interpretation. It argues that the UK initiative is deliberately and directly designed to impact upon devolved powers - or, more precisely, powers currently held in Brussels which affect devolved issues.