Tracking Scotland's wildfires from space

- Published

- comments

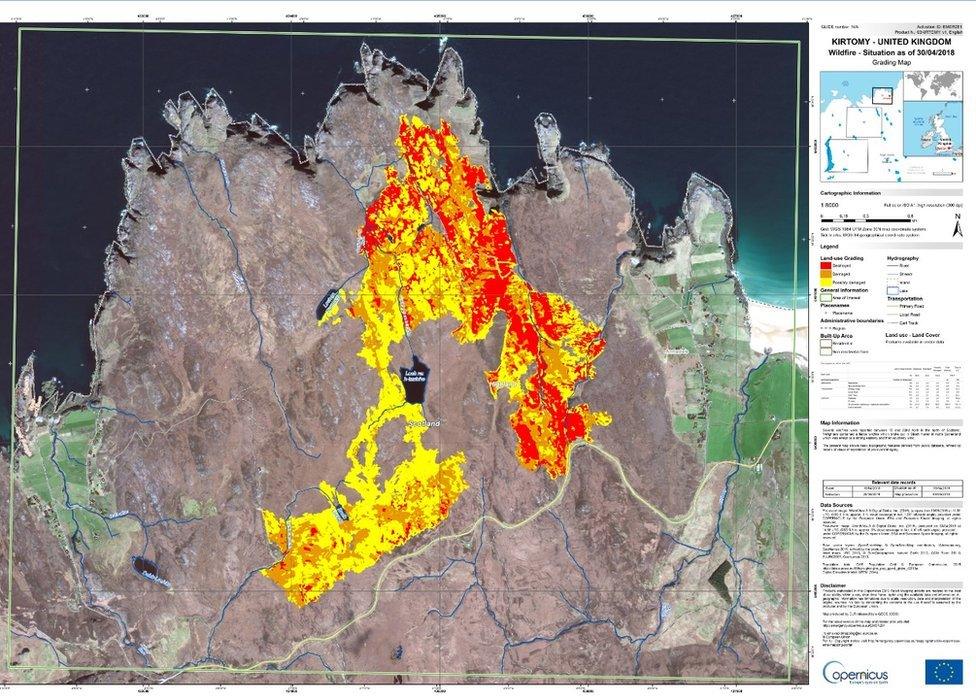

A satellite images show wildfires in north Sutherland

In this summer of wildfires across Europe, breakthroughs in satellite imaging are helping scientists in Scotland better understand them in real time.

Specialists from Scottish Natural Heritage are using data from orbit to assess damage from wildfires in Skye, Torridon, Rum and Sutherland.

A major wildfire broke out on the isle of Rum in April

They are using European Space Agency's Copernicus programme, the world's biggest Earth observation mission.

From the summit of Beinn a' Bhragaidh above Golspie in Sutherland, George Granville Leveson-Gower looks down disapprovingly. At least we must imagine he does as he's a statue.

The first Duke of Sutherland - for it is he - is overlooking a mess.

A wildfire has scarred the slopes nearby. It began in July and burned for several days before it could be brought under control.

The Duke of Sutherland's statue looks down on the wildfire scarred slopes near Golspie

It's ugly from afar and up close it is even less picturesque.

It is crunchy underfoot - crunchy and black.

The wildfire has left a crunchy mess under foot

Ash and a few charred roots are all that remain of the heather and gorse. Part of a plantation of trees has been burned, or scorched a dead brown.

In some patches the ash is not black but orange, a sign that the soil itself has burned.

Some green shoots poke through the charred moor grass

Nature is already fighting back. Some green shoots of moor grass are poking through the black. But heather could take more than a decade to recover - if other plant species don't establish themselves first.

Dr Graham Sullivan, uplands adviser with Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) surveys the scene.

Animal and plant habitats have been wrecked. And if peat bog burns it's especially bad news for the environment.

Dr Graham Sullivan is uplands adviser with Scottish Natural Heritage

"It burns off carbon that's been stored for decades and centuries and thousands of years," he says.

"But it also reduces the ability of the bog to actually sequester more carbon because it burns the plants that are incorporated into the peat and thus store carbon."

So while some wildfires occur in nature they are bad news. But just how bad?

If only there was vantage point from which we could see the full extent of the damage.

There is. Space.

As part of the Copernicus earth observation programme of the European Commission and European Space Agency (ESA), two satellites are constantly beaming back data about the state of the land below.

Sentinel-2A and -2B are part of a constellation of Earth observation missions. The pair orbit the Earth 180 degrees apart, so one is always looking at the sunlit face of the planet.

The data they send back means Lachlan Renwick, SNH's geographic information systems manager, can call up to his laptop images of fire damage here in Sutherland and across Scotland.

"The key thing for us is being able to get good quality imagery," he says,

"And in Scotland we have an issue getting cloud-free imagery.

Lachlan Renwick gets good quality imagery of the fire damage

"The Sentinel imagery is particularly good because we have two satellites and they're coming over on a regular basis.

"We get imagery every two to three days and that's really good. That's a big improvement on what we've had available to us before."

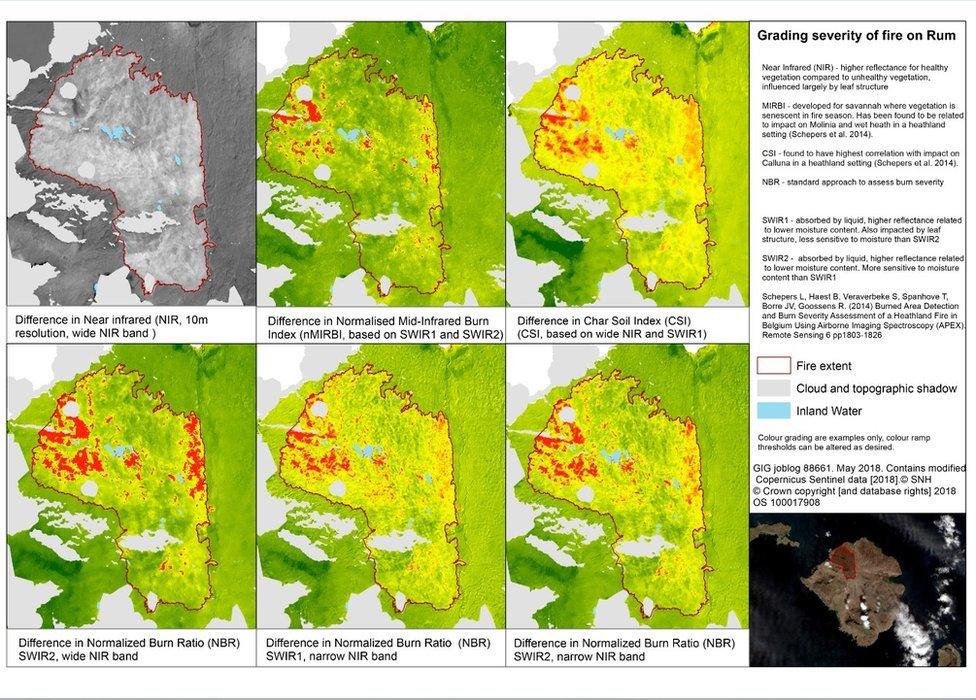

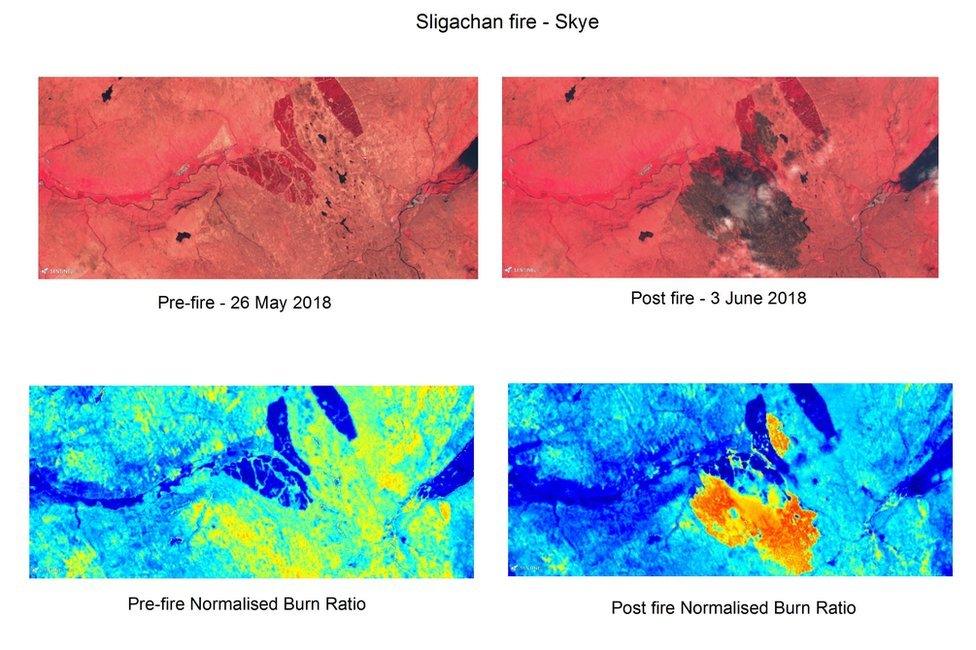

He looks at satellite images of fires on the islands of Skye and Rum.

The true colour shots show how far fires have spread. But he is able to learn more.

The data from orbit is processed to show how much light is reflected at different frequencies. That shows in detail how badly the fire has damaged plants and the soil beneath.

The information means Dr Sullivan and his colleagues can get to work to mitigate the worst of the damage:

"One of the first steps to understanding things is to quantify them.

"So from that point of view it's useful.

"But it also means that if we're thinking about how we can assist these habitats to recover, having information on severity enables us to target how we might carry out any actions that can help recovery of that vegetation."

Something as seemingly simple as deciding whether and when sheep are allowed to graze will dictate if heather recovers or purple moor grass takes over.

Taking pictures from space is nothing new. But the Copernicus programme offers speed. High quality information can be delivered to habitat specialists and local people within days.

When the clouds don't clear, and a Sentinel won't be back overhead in time, there is a fallback.

That happened when a big area of northern Sutherland burned. SNH needed information faster than the Sentinels could get it. So they called on the Copernicus emergency management service.

That commissioned a Spanish commercial satellite to take a look, the first time that system had been used for Scotland. The result was information that would otherwise have remained invisible until it was too late.

SNH are still in the early stages of using the system.

Lachlan Renwick says it's a game-changer because the Copernicus system can monitor more than just fire damage. The data could be put to other uses they are just beginning to imagine.

And while satellites can't put out fires, it is the first step towards safeguarding the land down here - from up there.