Parkinson's patients help in the lab

- Published

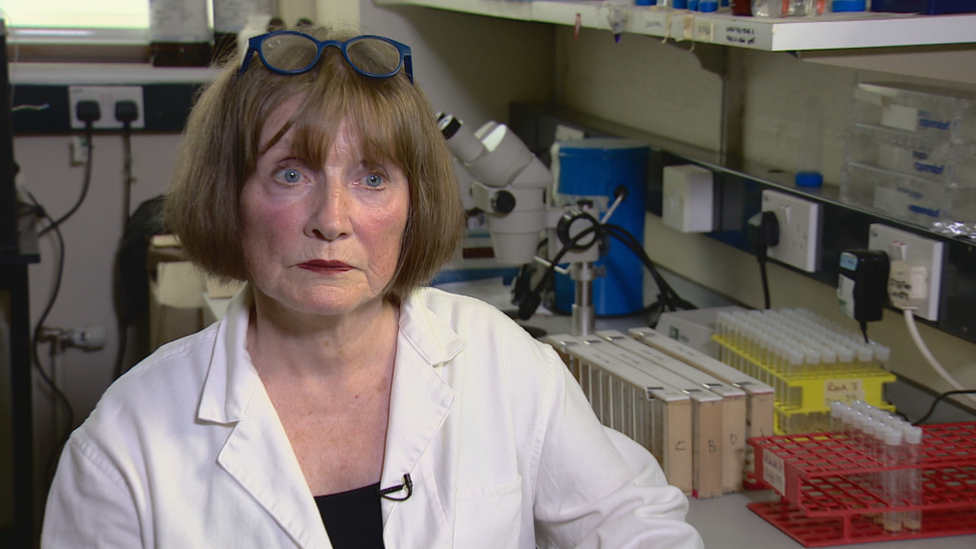

Frances Taylor was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease 17 months ago

People with Parkinson's are conducting laboratory experiments in a bid to help researchers find a cure.

The neurodegenerative disorder affects about 12,000 people in Scotland but scientists say efforts to develop treatments have "stagnated".

An Edinburgh University pilot project is encouraging patients and other volunteers to assist in simple lab experiments at a pre-clinical level.

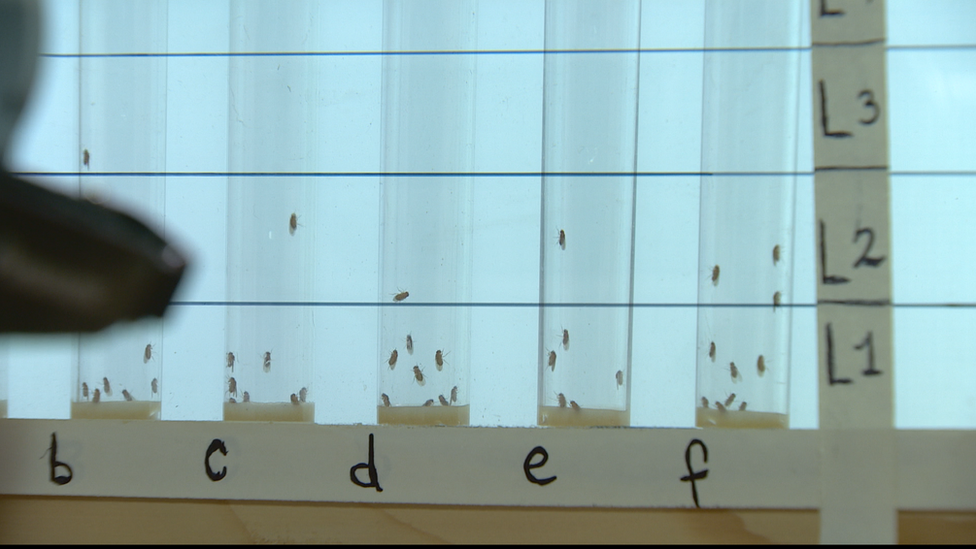

The experiments involve screening drug treatments on fruit flies.

Lack of investment

There is no cure for Parkinson's and there has been no new treatment developed since L - Dopa was introduced in 1967.

It is a complex condition and scientists say the difficulty getting drugs successfully through clinical trials has led to a lack of investment by pharmaceutical companies in further research.

Earlier this year, drugs giant Pfizer announced it was pulling out of early stage research into Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

Scientists said it was more important than ever that those with a vested interest in successful treatments had a voice in research.

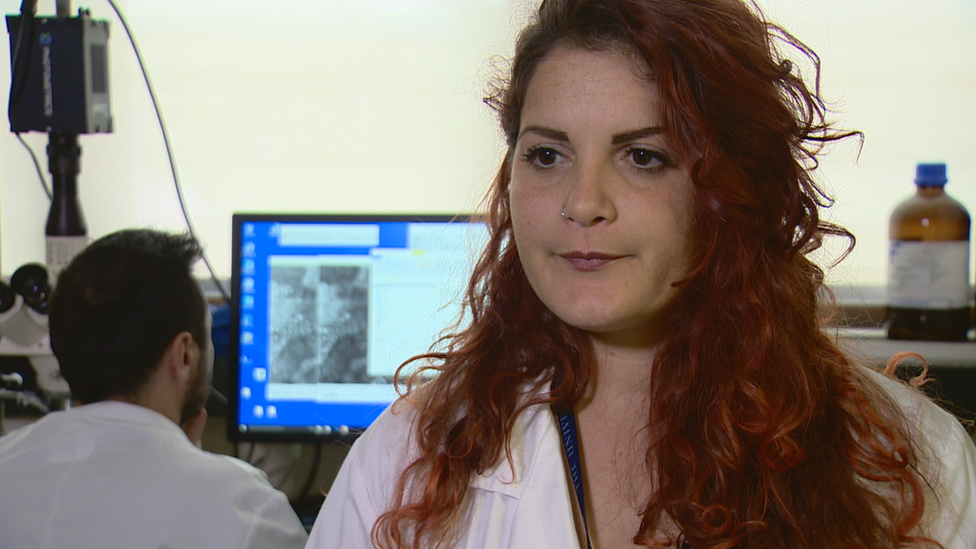

Dr Valentina Ferlito is leading the Crowdlabbing project

Dr Valentina Ferlito, who is leading the Crowdlabbing project at Edinburgh University, said the scientists had developed a method of early stage drug discovery that used fruit flies to test hundreds of compounds of different origin.

The common fruit fly - Drosophila melanogaster - and humans share almost 75% of the genes that are related to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

Dr Ferlito said the flies provided a good model for early stage drug screening as they were cheap and easy to breed in the lab.

Her team has developed protocols that allow non-scientists to help with monitoring the results of the screening experiments.

Fruit flies are used in the screening process

One of the Crowdlabbing volunteers is 71-year-old Frances Taylor, who was diagnosed with Parkinson's Disease 17 months ago.

She said: "It's very heavy when you are given a diagnosis.

"It's painful. It's like a body blow. You are scared. You don't know at which rate it could progress."

Ms Taylor said taking part in the research was interesting and rewarding.

"It's valuable because you do feel you are doing something in your own small way," she said.

"It is not an ego thing. It is a desire to be helpful and to assist."