On the trail of the live calf export lorries

- Published

'Some mothers will bawl for days'

Investigating the controversial world of the calf export trade was never going to be easy.

I knew I would have to try to examine every part of the entire supply chain, from source right the way through to sale.

Part of that supply chain is the incredible journeys the cattle are taken on.

For me to fully understand the trade, I wanted to try to see for myself what those journeys are like.

After speaking to contacts, it became clear that shipments of calves were being transported from Scotland to Spain and Italy.

Last year more than 5,000 were shipped abroad, up from just a few hundred the year before.

But where exactly were they going? And why?

I was passed some journey logs which had been logged and approved by a government department which dealt with livestock export.

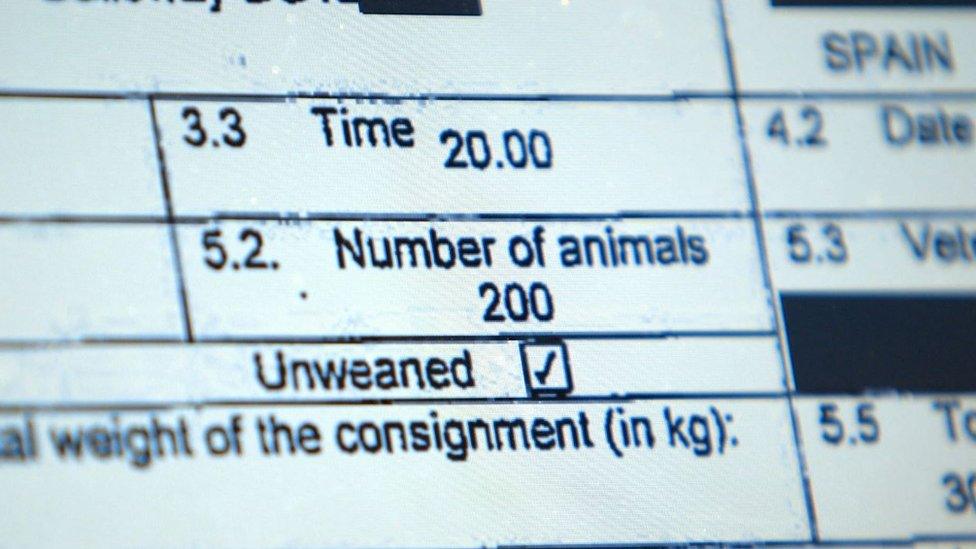

Most of the information was redacted. But there was enough for me to see that up to 200 calves were being shipped out of Scotland every fortnight, all of them unweaned.

Documents showed that the animals were unweaned

They left the same farm in Scotland aboard a livestock truck and were driven to Cairnryan where the truck would board the midnight boat for Northern Ireland.

Every week I sat and watched as livestock truck after livestock truck made the journey along the A75 to Cairnryan to board the boat.

One truck soon stood out. It matched the exact timings given on the paperwork. And sure enough, on closer inspection, it was filled with calves.

I decided that the next time the truck was in Scotland collecting calves, I would be with it. And I wouldn't let it out of my sight until it got to its final destination.

Two weeks later I found the truck on the main road to Cairnryan. It was filled with calves. It boarded its usual midnight crossing to Northern Ireland and the port of Larne.

Sam watches the port as she tracks the lorry full of calves

Immediately on arriving, the truck pulled into an inspection centre.

Larne Port is currently the only approved port of entry for livestock imports in to Northern Ireland.

I watched and filmed as a man with a torch spent more than half an hour inspecting what seemed like every animal on the truck.

I am no expert, but the inspection appeared incredibly thorough and highlighted to me what an incredibly well-oiled machine the export trade is.

By three that morning, the truck was back on the road.

On the trail of the cattle in Northern Ireland

You would think that following a huge articulated livestock truck which was limited to how fast it can travel would be easy.

It's not. I had to film, I had to ensure that I was capturing the true face of the export trade, and yet to be spotted or noticed would mean my trail was over.

The truck headed into the quiet rural backroads of Northern Ireland. And so began my first challenge.

One which I failed in. I lost the truck.

The dark and small roads proved too much in my attempts to keep a safe distance from being spotted and eventually I had to pull back. The truck - and its calves - disappeared into the darkness.

I knew they were heading to one of two licensed control points in Northern Ireland.

Was I at the right port?

There, the cattle would be unloaded, fed and rested for 24 hours. But which control point? And in the unfamiliar rural landscape, it would be too hard to see whether our cattle were at either address.

I had to make my next move carefully and that meant going back to the paperwork.

The journey logs showed me that Cherbourg in France was the most popular port for livestock trucks from Ireland and so I knew that if I had any chance at all of finding the truck, I had to get to France in time for the arrival of the overnight boat.

Several hours to Dublin, one flight to Paris and a long drive later, I arrived at Cherbourg port.

I had less than half an hour before the boat was due in.

Was it the right one? Was I at the right port? Was I even in the right country?

All I could do was set my camera up and hope for the best.

Waiting for the truck to drive off the ferry

Eventually the boat came in and truck after truck came off.

Some loaded with calves, others sheep. Just as I was losing all hope, there it was. The last one off. My trail of the cattle truck was back on.

I followed the truck for what seemed like an age.

Four hours after leaving Cherbourg, the truck came to a stop at a service station.

Export chain

By law the driver has to stop for a rest every four hours for at least 45 minutes. While he took a break and got some food at the café, I got my first chance to see the calves up close.

And that was when I was in for a surprise.

The calves I had seen on the truck earlier in Scotland and Northern Ireland weren't there.

These cattle were older. Yet it was exactly the same truck and clearly a key link in the export chain.

So I decide to carry on with the trail to see where they end up.

The driver produced a stick from the truck

When the driver returned, he checked the animals.

He appeared to notice a problem with one of them and, reaching down into a small cabin in the side of the trailer, he pulled out a long stick.

I watched as he pushed it several times through the slats of the truck into where the cattle were.

Once satisfied all was well with the cattle, the driver set off again.

Later that night, near the Swiss border, the truck pulled off the autoroute and into an anonymous facility in an industrial estate.

Control point

It was a control point, like the ones I didn't get the chance to see in Northern Ireland. I watched as the cattle were unloaded, presumably fed, and then rested.

The next 24 hours were tough. I had been on the road for four days and was exhausted.

Yet having lost the truck once, I wasn't going to lose it again and so I sat outside the control point and kept watch.

The following evening, the driver moved the truck into the loading bay and began to load the cattle.

The stick was out again, but this time it was clear to see.

I watched as the driver repeatedly hit the cattle, forcing them back into the truck they had spent the majority of the last few days in. And again we were back on the road.

It was now my fifth night following the cattle truck. As dawn broke, we were as far east as Milan.

Just as we neared Venice, the truck pulled off the main road and drove down a dusty track.

Previous journey logs have shown calves and other cattle being transported to Northern Italy from Scotland, those journeys taking six days.

I knew I was nearing the final destination.

Finally, six days after first starting out, our truck came to a stop.

I filmed, hands shaking and utterly exhausted, as the driver reversed back into a barn and began to unload the cattle.

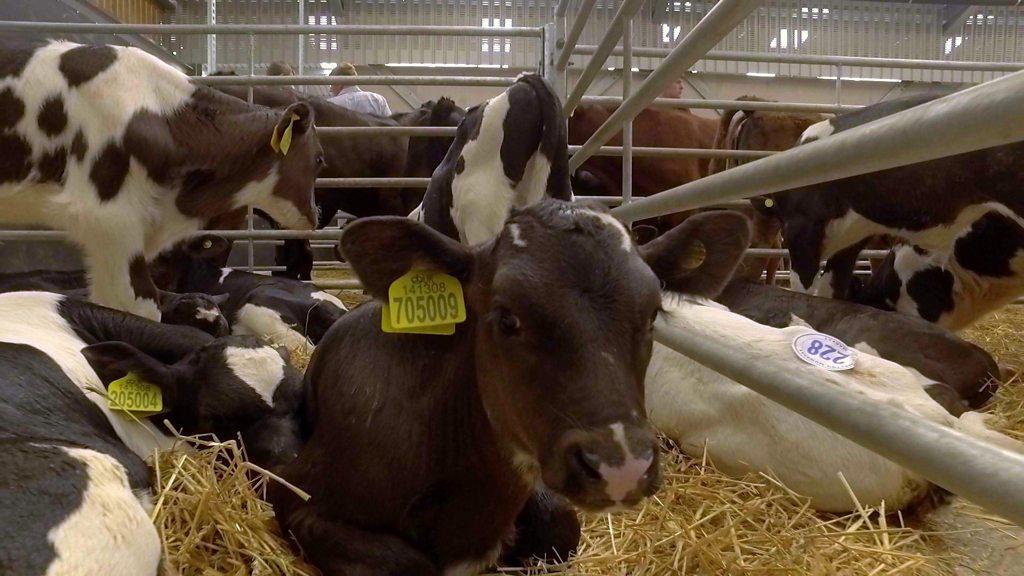

The calves are taken on long journeys to Spain and Italy at just three weeks old

My trail was over.

In the hours that followed, I did my research.

The area the cattle were taken to was in the heart of the "fattening" world.

It's where young cattle are brought to be fattened as quickly as possible before slaughter.

When I contact the hauliers, they don't want to be interviewed.

But they confirm that when the truck left Scotland, it was carrying calves.

They were dropped off somewhere in Northern Ireland to be shipped on to Spain.

The animals I saw from Cherbourg onwards were picked up in southern Ireland and taken to Italy - some for breeding, others for fattening and then slaughter.

The company said the truck was specially adapted to keep the animals cool.

With regards the stick, the company said the driver used the stick both to ensure the cattle were standing and fit for the journey - and to protect himself when moving large animals.

If you want to speak to BBC Scotland Disclosure about this investigation, or another story, follow the team on Twitter @BBCDislosure, external. And remember, you can watch this Disclosure investigation on demand on BBC iPlayer.

- Published10 September 2018

- Published10 September 2018

- Published10 September 2018