Turning down the volume: Tackling the problem of 'noisy' electricity

- Published

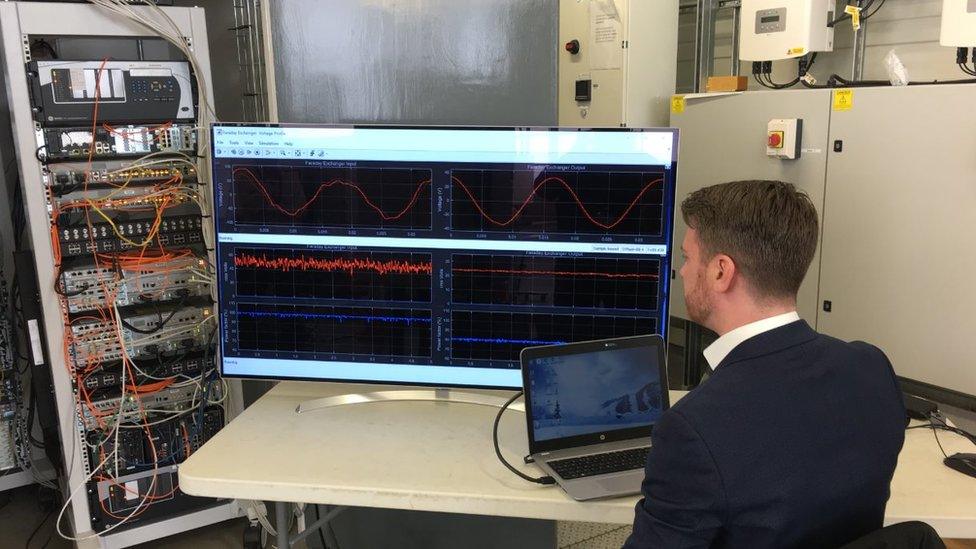

Edinburgh firm Faraday Grid is aiming to make the electricity system "more robust and flexible"

The drive to reduce our carbon emissions has produced an unintended consequence: poorer quality electricity.

An Edinburgh company has created a new approach which it says will transform the way electric power is delivered.

It will still come down the same transmission lines but is predicted to be cheaper and more efficient than before.

Whether it's a hot shower or cold milk, we tend not to think too much about the power behind it.

But the rise of renewable energy is creating new problems for the electricity grid.

In the 20th Century our electricity supply was straightforward: a relative handful of big power stations drove big generators. The power came from the top down from them to us.

That has changed. Many big power stations still exist, the flywheels of their huge generators creating electricity at a relatively steady frequency of fifty cycles a second (50 Hz).

But increasingly there are smaller power producers at the other end of the chain. Solar panels on our roofs and wind turbines power individual homes or communities.

The rise of renewable energy is creating new problems for the electricity grid

They can also feed the surplus back into the grid, sending electrons in the opposite direction to the one for which it was designed. The system has become top-down and bottom-up at the same time.

The issue of what's called intermittency is well understood: you can't generate solar power if it's dark, wind power in calm weather.

But these new sources carry with them another problem: the electricity they produce can be far from the smooth 50 Hz which is the system's ideal.

Instead there are harmonics and distortions. The electricity is "noisy".

Prof Campbell Booth heads the department of electronic and electrical engineering at Strathclyde University. He says poor quality electricity has serious implications for the suppliers.

"Our power is provided via what they call a three phase system - so there are actually three wires carrying an equal amount of power," he says.

"Some of our renewable energy sources connect to just one of these phases. That can result in 'unbalance' and that can cause heating in the power transformers that transform high voltage to low voltage.

"It can also cause heating in the neutral cables which are part of the supply system."

The way our electricity is supplied has been changing

A lot of thought and work is going into dealing with a much more volatile energy supply across the industry.

One response is coming from the Edinburgh company Faraday Grid.

The firm's founder and chief technology officer Matthew Williams says their aim is nothing less than to change the architecture of the electricity system.

"It's based on an entirely new device called a Faraday Exchanger," he says.

It is a large grey cabinet run from a computer display.

"The Faraday Exchanger is able to control voltage, frequency, power factor and balance across phases.

"Which is all very technical, but what it ends up meaning is that the electricity system is much more robust and flexible."

He likens the new approach to the switch from the copper wires of the old telephone system to the fibre optics of the internet.

"We have an electromagnetic device and a control system that allows us to control the power flow through the device without using electronic circuits, which is very expensive at higher power levels and introduces noise into the system."

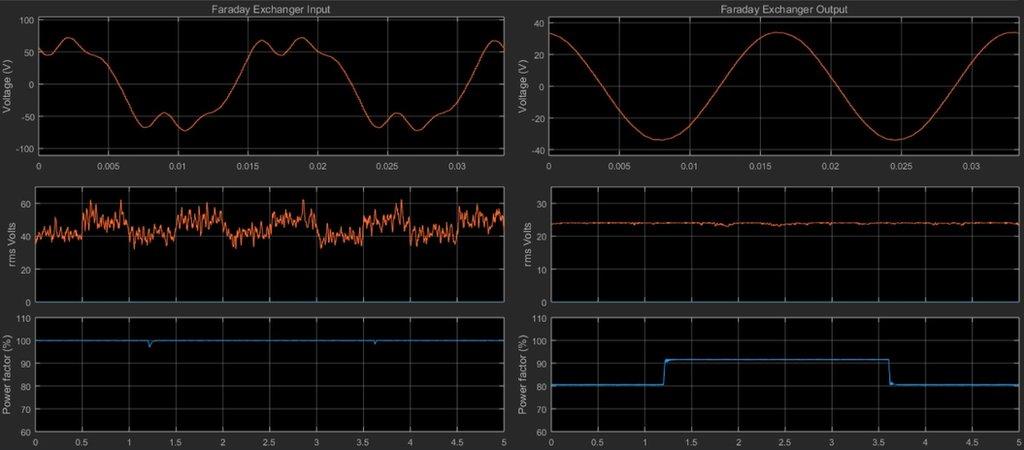

The Faraday Exchanger can control the voltage, frequency, power factor and balance

The monitor shows a split screen. The ragged traces on one side show poor quality electricity being fed into the device. On the other side the output graphs show altogether cleaner, less noisy power.

This is still a young company but it has already grown from just four employees to almost 100.

Its ambition seems daunting: to replace existing transformers and substations with Faraday Exchangers in every locality.

The first is expected to be installed in the UK's electricity transmission system early in 2019. Installations on continental Europe and the US are also planned.

The company say electricity suppliers could carry out the swaps within existing budgets as old transformers come to the end of their lives.

Its chief economist Richard Dowling says consumers stand to benefit from a decentralised grid: "The sun's free and the wind's free but that's not translating to lower power bills for households because the cost of transporting that type of power is really expensive.

"What we're actually doing is trying to improve the efficiency of the grid so we can transport the power from the generation source to the home at the lowest possible cost."