WW1 leader Field Marshal Haig was not a 'pantomime villain'

- Published

Statue of Field Marshal Haig at Edinburgh Castle

The reputation of Scottish World War One leader Douglas Haig has been controversial but it is finally being recovered from the ruins by historians.

Field Marshal Haig was a national hero and was rewarded with the title of earl for leading Britain to victory.

From the end of the war 100 years ago, until his death of a heart attack in 1928, Edinburgh-born Haig remained a popular figure.

Field Marshal Douglas Haig was British senior officer during World War One

For his funeral at Westminster Abbey - one of the earliest state occasions broadcast live by the BBC - a million people are estimated to have lined the streets of London.

This was more than for Princess Diana's funeral almost 70 years later.

But as the memory of the conflict faded, Haig's reputation changed dramatically.

He came to symbolise everything that was wrong with the war and was blamed for sending thousands of soldiers to needless deaths in the bloody battles of the Somme and Aras.

The funeral procession of Earl Haig

Haig's charger in the funeral procession, with the Field Marshal's boots reversed in the stirrups

As pacifism and appeasement grew through the 1930s, he was derided as one of the "donkeys" who sent so many "lions" to their deaths on the Western Front, a popular phrase used for decades to complain about perceived military incompetence.

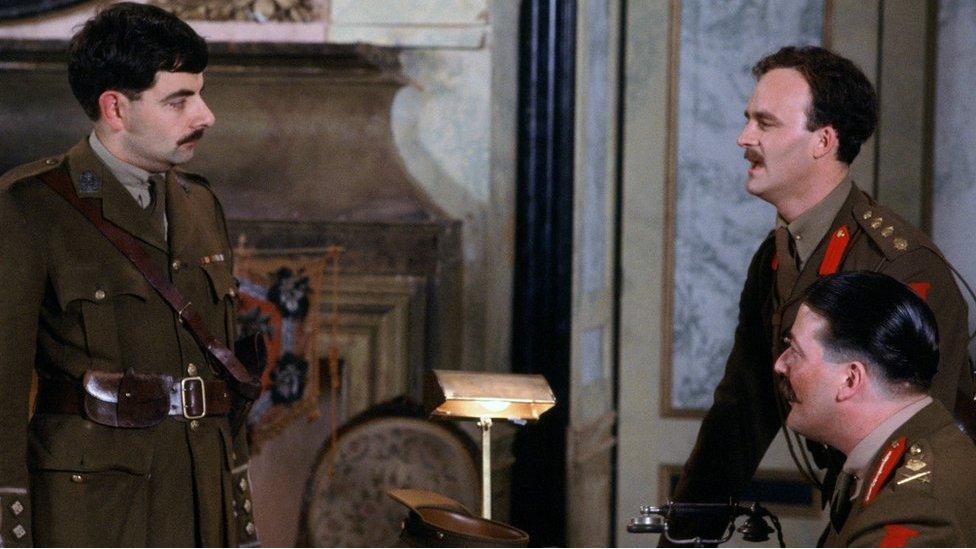

It was an image which persisted with the 1963 musical "Oh! What a Lovely War" and the BBC series "Blackadder Goes Forth", which satirised the tactic of sending large numbers of men out of the trenches to advance towards the enemy guns.

It claimed the aim of every military effort on the Western Front was to move Haig's drinks cabinet six inches closer to Berlin.

The BBC's Blackadder Goes Forth lampooned Field Marshal Haig's tactics

However Prof Gary Sheffield, of the department of war studies at Wolverhampton University, said Haig deserves better than to be regarded as a "pantomime villain".

He said the field marshal's record should not be viewed through the prism of hindsight.

Prof Sheffield said Haig, who was born in Edinburgh in 1861 into a life of privilege, was very much a late 19th-Century figure.

A childhood portrait of Douglas Haig in Edinburgh from about 1870

The historian said it was not right to judge him, either in personality or approach, by 21st Century standards.

Having presided over the horrific slaughter of the Somme offensive in 1916 and the equally bloody battle of Aras the following year, Haig had undoubtedly learned valuable lessons, Prof Sheffield said.

These paved the way to ultimate victory in 1918, with a series of victories unmatched in Britain's military history, he claimed.

"It makes little sense to compare him to any other previous general because actually warfare changed so profoundly during the First World War," Prof Sheffield said.

"He was a war manager as much as anything else, managing this vast army, helping it to train, equip, as well as being a general on the battlefield."

The Field Marshal's interest in the welfare of injured servicemen led to the establishment of the Earl Haig Fund

The historian also said that Haig's role as an advocate for veterans reflected well on him.

He said that even before the Armistice, Haig had worked to help servicemen left disabled by war wounds.

The Earl Haig fund he established still provides support for those wounded or widowed by conflict.

Earl Haig watches the stamping of poppies by ex-servicemen during a visit to the British Legion poppy factory at Richmond in 1926

The poppy factory in Edinburgh, established by Earl Haig's wife, is at the forefront of the immense fundraising effort and is her husband's legacy today, according to its manager Major Charlie Pelling.

He said: "Haig was a Scot. He was born and educated in Edinburgh.

"I think he thought it was extraordinarily important to set up a fund here in Scotland to help provide benefit for all the Scottish ex-servicemen and their families that had been killed, maimed or left widowed during the First World War.

"So yes, I think he regarded the fund in Scotland as extremely important."

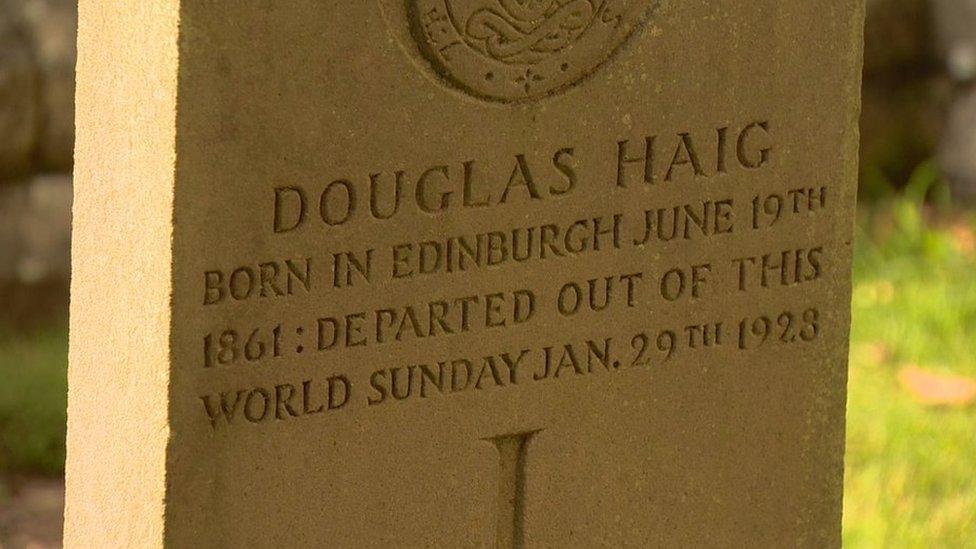

Earl Haig is buried at Dryburgh Abbey in the Borders, close to his family home

After his death, Field Marshal Haig was buried at Dryburgh Abbey where a simple stone marks the grave of the general who led one of the biggest armies Britain had ever sent to war.