The day the German navy surrendered in the Forth

- Published

The German fleet was escorted into the Firth of Forth

Ten days after the Armistice ended the fighting in World War One, the British navy celebrated a decisive victory without a shot being fired when the entire German fleet surrendered in the Firth of Forth.

It was the greatest gathering of warships the world had ever witnessed.

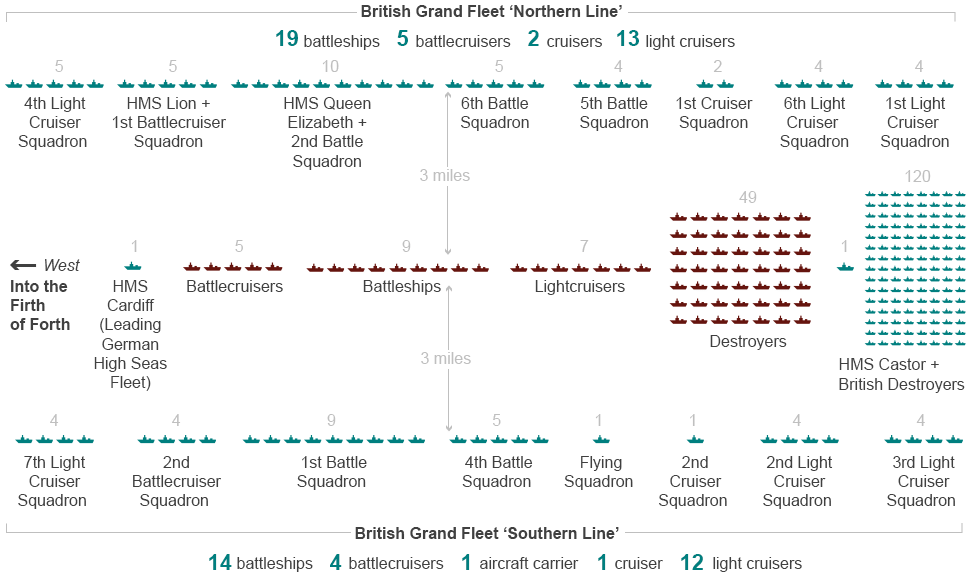

Nine German battleships, five battlecruisers, seven light cruisers and 49 destroyers - the most modern ships of the German High Seas Fleet - were handed over to the Allied forces off the east of Scotland.

The 70 German ships were escorted into the sheltered estuary north of Edinburgh by hundreds of Allied ships and aircraft.

A photograph of the ships in the Forth taken by Charles Wright who was a photographer at East Fortune

"It must have been some sight in the Firth of Forth that day," says Ian Brown from the National Museums of Scotland.

"It was a sight that had never been seen before and will never be seen again," he says.

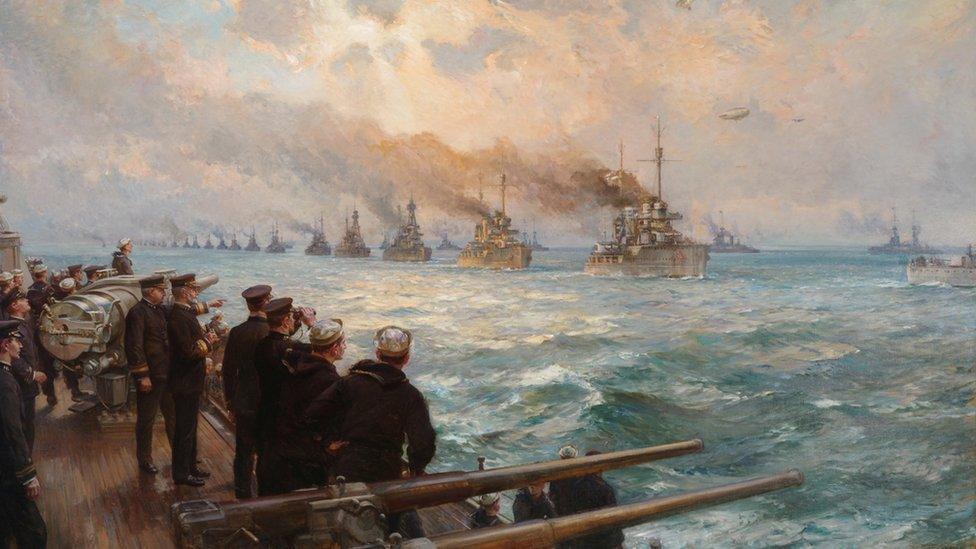

The surrender of the High Seas Fleet observed from the battleship USS New York. The painting is by Bernard Gribble.

Operation ZZ saw the mightiest gathering of warships in one place on one day in naval history.

The man in charge was the Royal Navy's commander-in-chief Admiral Sir David Beatty.

Under his command, in the early hours of 21 November 1918, the Grand Fleet began to raise steam and ease out of its moorings.

More than 40 battleships and battlecruisers set a course due east through the fog for the open water of the North Sea, about 50 miles beyond the Isle of May.

They were joined by more than 150 cruisers and destroyers heading for a final rendezvous with its mortal enemy - the German High Seas Fleet.

Arrangements had been made in advance for the surrender but the British navy was still ready for action and on a war footing.

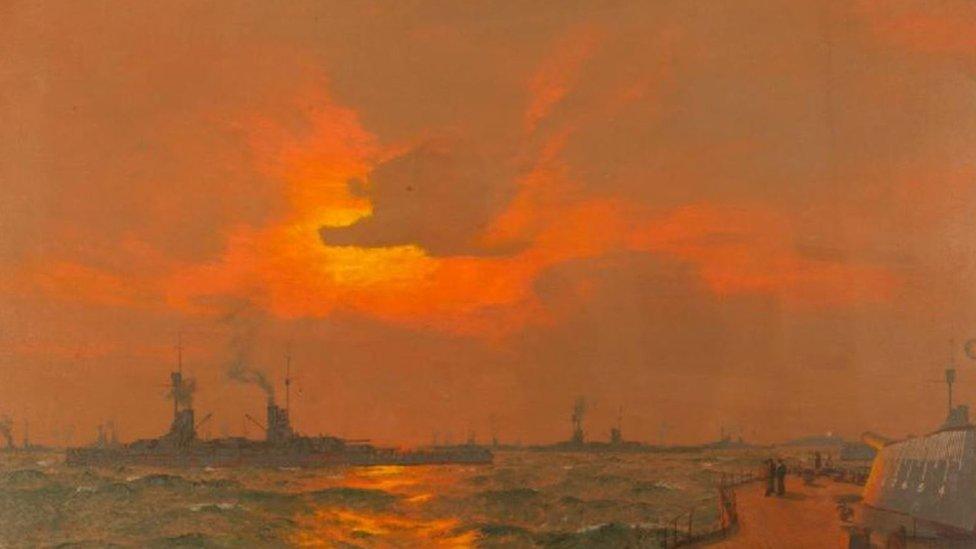

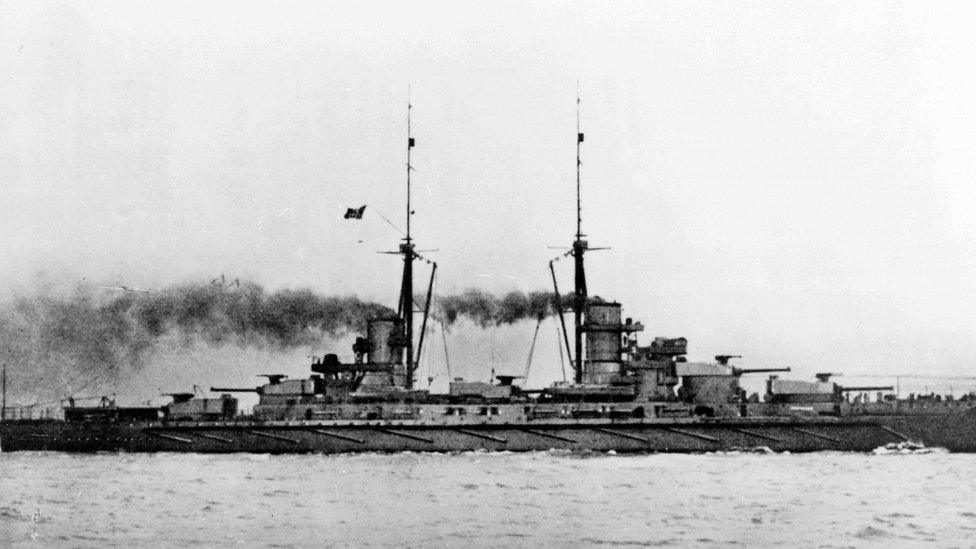

The German fleet at anchor off Inchkeith after the surrender

The Royal Navy was keen not to give the German fleet - the second biggest in the world - the chance to change its mind.

The Germans had been instructed beforehand their guns were not to be loaded and everyone but the engine crew were to be on deck.

In contrast, Admiral Beatty gave orders that his ships were to be ready for action with guns ready to be loaded at a moment's notice.

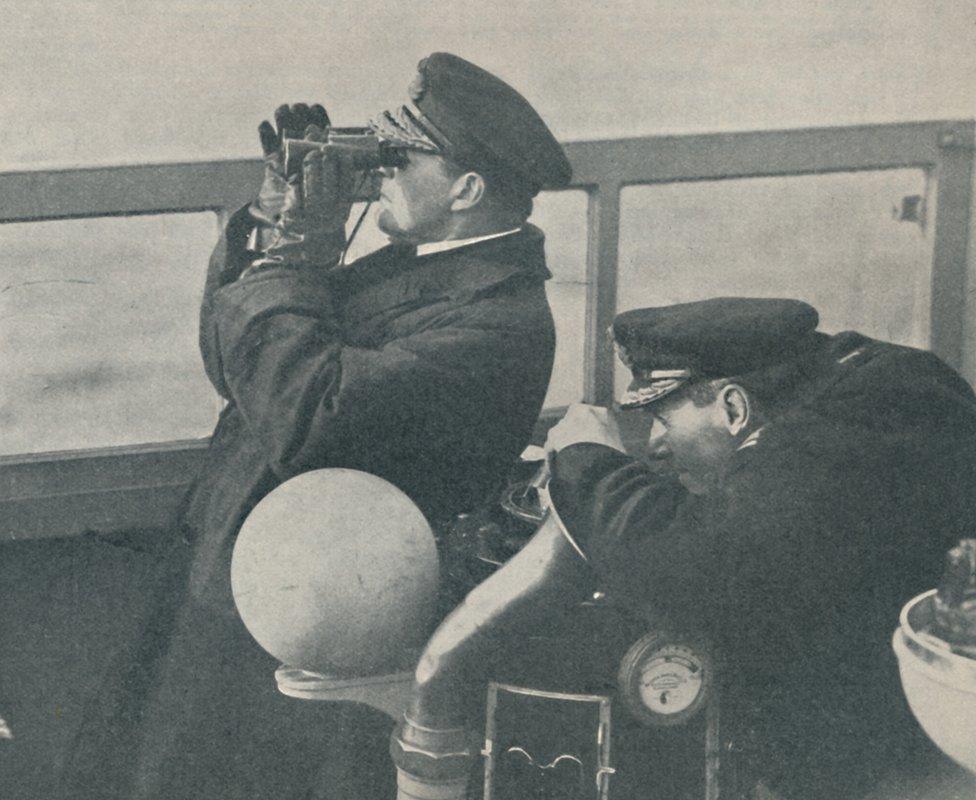

Admiral Sir David Beatty watching the German High Seas Fleet heading for the Firth of Forth

About 90,000 men of the British, American and French navies were aboard the ships.

As the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet sailed into the North Sea, it formed two massive columns six miles apart.

Just before 10:00 it met the Germans and their hulking crafts were led to their surrender by the British light cruiser HMS Cardiff.

"It was like a tiny little dog escorting in all these young bulls," says Mr Brown of the National Museums Scotland, which has a collection of photographs from the day.

Royal Navy light cruiser HMS Cardiff leading the German battle cruisers into the Firth of Forth

After sailing out beyond the Isle of May, the two Allied columns swung around 180 degrees and formed an overwhelming escort on either side of the Germans as they led them back into the Firth of Forth.

"It was a wonderfully choreographed manoeuvre," says Andrew Kerr, an Edinburgh lawyer and local historian who has studied the handover.

By early afternoon, the German ships were anchored under guard east of Inchkeith.

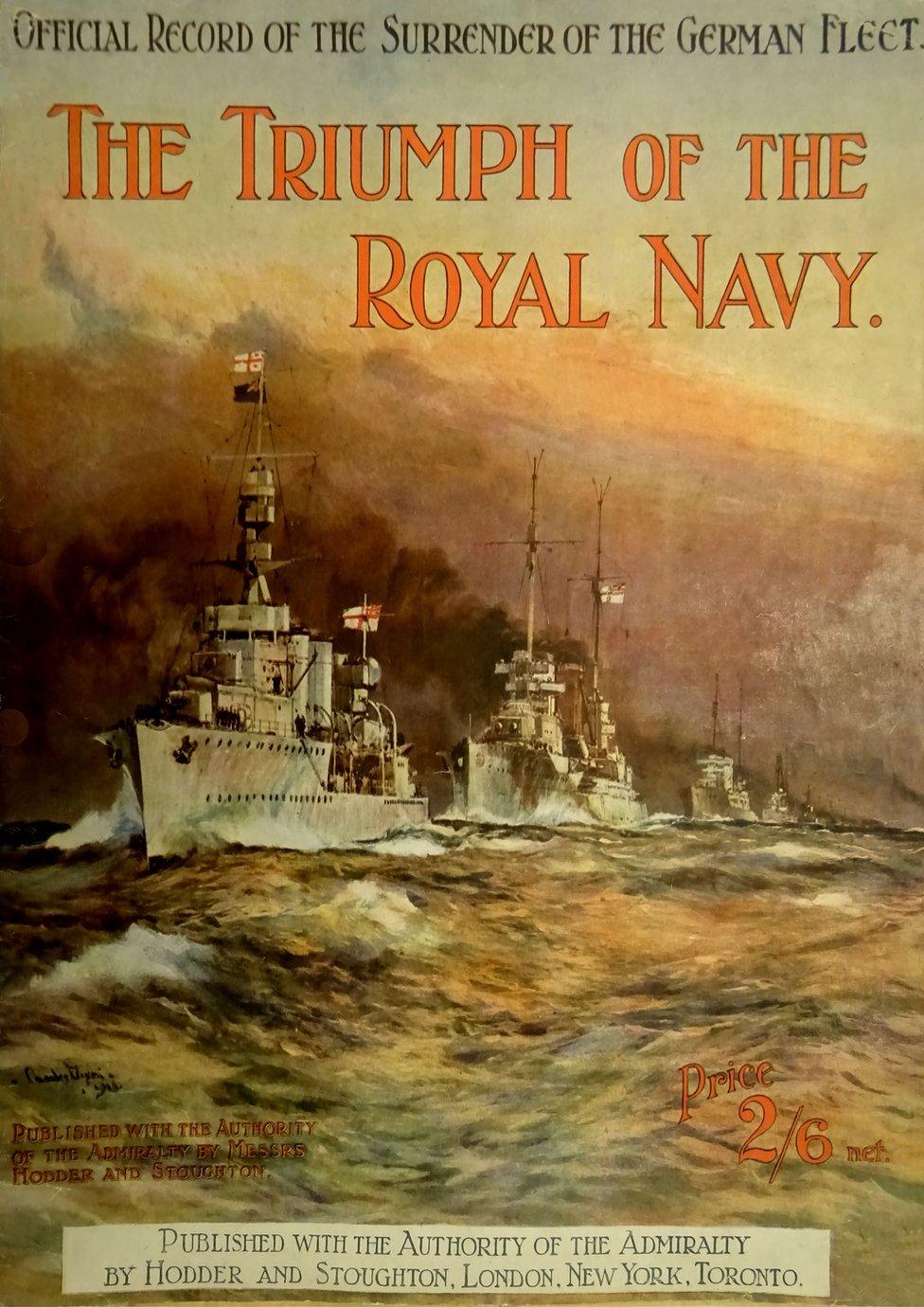

An image from the Official Record showing the three flagships - Queen Elizabeth, New York and Friedrich der Grosse

The rest of the British and allied fleet returned to its anchorage above and below the Forth Bridge, says Mr Kerr.

He says recently-rediscovered anchorage plans for the surrender show the German ships boxed in by British battleships and cruisers, with the destroyer lines extending eastwards into Aberlady Bay.

According to Mr Kerr, Rosyth in the Firth of Forth was the base for the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet.

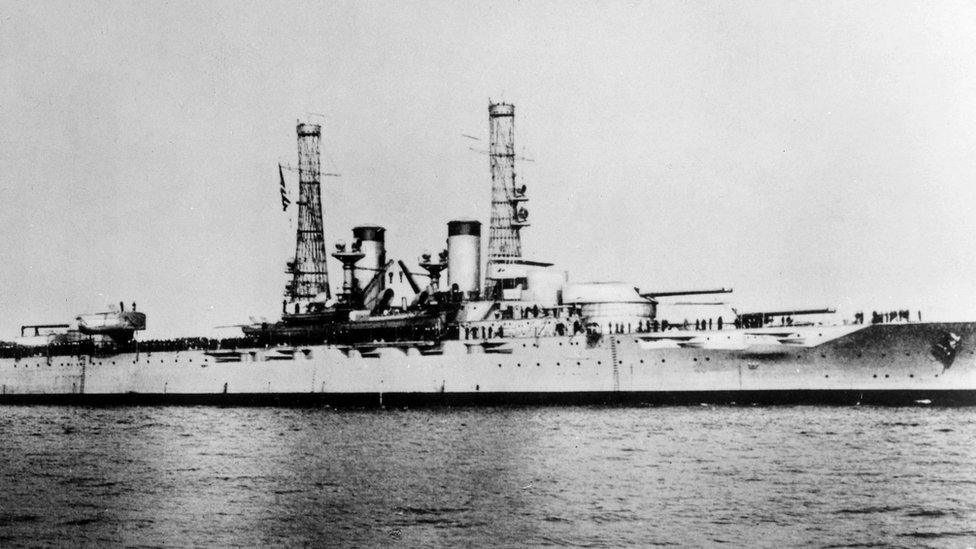

Italian liner "Giulio Cesare" was an escort vessel during the internment of the German fleet

The fleet had been based at Scapa Flow in Orkney from the beginning of the war until the Forth was made safe enough to defend in early 1918.

"It had taken all that time to make the estuary here safe enough for the ships," he says.

Liner "Texas" as an escort ship during the internment of the German fleet at Firth of Forth- 1918

In a mark of the final surrender of the former enemy, Admiral Beatty issued the order for the German ensign to be taken down at sunset and not hoisted again without permission.

"That was it," says Mr Brown.

"'You have surrendered. You are now our prisoners'."

Mr Brown says the two largest naval fleets in the world had been incredibly important in WW1.

As an island nation which was dependent on imports to feed itself, Britain had to rule the waves.

Defeat at sea by Germany could have led to blockade, possible starvation and surrender.

The superpower fleets had met at the Battle of Jutland in 1916 and it was "debateable who won", Mr Brown says.

"The Germans say they won because they sank more British ships but the British say we won because the German navy never ventured out of port again," he says.

The Royal Navy's superiority in numbers was designed to make defeat in battle impossible and bottle up the Germans on the other side of the North Sea.

According to Mr Kerr: "Without the navy, the blockade of Germany would not have been possible.

"It was the blockade that led finally to the collapse of the German nation and the seeking of Armistice terms."

The blockade of Germany meant that by 1918 it was the Germans who were hungry, not the British.

'Ultimate humiliation'

Mr Brown says: "Just before the Armistice, the German navy had been planning to come out but there was a mass mutiny, basically the sailors refused to leave port.

"Then you have the Armistice and 10 days later you have the humiliation of having to come to one of the home ports of the Royal Navy."

"It is the ultimate humiliation for the German High Seas fleet."

Within a week the German fleet were escorted to Scapa Flow where they were interned until June 1919.

Having learned of the possible terms of the Treaty of Versailles, which would have shared the ships among the Allies, the caretaker German crew on board the ships scuttled them by opening flood valves and watertight doors and smashing water pipes.

A senior German officer declared at the time that this act had wiped away the "stain of surrender" from the German fleet.

- Published20 November 2014