Call to reduce number of children in care in Scotland

- Published

Parents and academics have called for greater support for families to try to reduce the number of children in care.

They also want a less punitive approach to child protection.

Research seen by the BBC shows the proportion of children in care away from home in Scotland has risen by 75% since 2004.

The Scottish government said the number of looked-after children had actually reduced over the past five years if you included those in their own home.

The official statistics for the rest of the UK do not include children looked-after at home, with regular supervision from social workers.

They are those who are placed by the local authority in "kinship care" with a friend or relative, in foster care or in a residential home.

'Culture of rescue'

Statistics gathered by Prof Andy Bilson, from the University of Central Lancashire, showed there was a steady rise in the numbers of children looked-after away from their home in Scotland, with a small decrease last year.

The rise was mainly in those cared-for by a relative or a foster carer.

Children cared-for in residential homes in Scotland has remained largely steady.

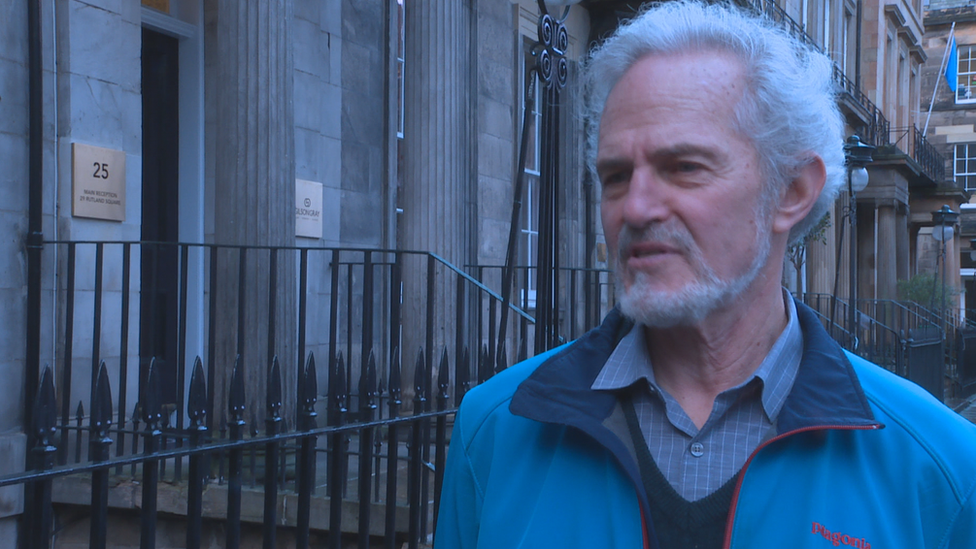

Prof Andy Bilson said parents felt blamed by investigations

More than 11,000 children were in care away from home in Scotland last year.

Prof Bilson, whose research focuses on the overemphasis on risk in the child protection system, said there was a "significant increase" and it was much bigger than other parts of the UK.

The professor said some statistical differences meant it was hard to compare Scotland with England "but even when you compare it with itself a few years earlier, many fewer children were taken into care".

He said he was concerned about a "culture of rescue", which saw too many children being taken away from their home.

'Investigation stigmatises parents'

Prof Bilson also found large differences in the way child protection was dealt with across Scotland's local authorities.

In some council areas, one in 10 children were investigated before their fourth birthday compared with one in 100 in neighbouring areas.

The average across Scotland was 4.4%, or one in 23 children investigated by the time they were four.

He said three-quarters of children on the child protection register had never had concerns about sexual or physical abuse.

The main areas of concern were neglect and emotional abuse.

He said the concerns were often caused by parents' lifestyles or the way they deal with their children.

The professor said the system had become much more aggressive towards parents and much more keen to blame them rather than help them.

"Investigation is not a good way to help parents," he said

"It stigmatises them. They feel blamed."

He said this made parents more defensive and it was much harder to get to the truth and help children.

Campaigners are calling for Scotland to adopt a model used in New York which sees parents trained to work alongside families and professionals.

The US model

David Tobis says the New York scheme could work in Scotland

David Tobis set up a scheme in New York that trains parents to become advocates for other parents and help them access the support and services they need.

It has seen the number of children in care in New York fall significantly.

Mr Tobis has been in Scotland looking at how parents could set up a similar system here.

"When we started working in New York in the 1990s, it had one of the worst child welfare systems in the US," he told the BBC.

"Almost 50,000 children had been removed from their families. There were also many other problems.

"Kids stayed in care too long, there were lawsuits against the city for failing to help families."

Mr Tobis said the idea was to get parents, who had a voice in the welfare system, to work alongside professionals - either on their own cases or in shaping what policies were put in place.

"We got parents at the table working with other parents and professionals and that contributed to a significant reduction in the numbers of kids in care," he said.

"There are a number of elements of that which could be applied here in Scotland."

Getting the children back

Heather Cantamessa thought she would never get her children back

Heather Cantamessa, from Seattle in the US, had her children removed when she was struggling with substance misuse and mental health problems.

She now has them back and works as a parent advocate to support others.

"I needed help but was scared to ask for it because I heard that if you asked for help you would get your children taken away and then once they were taken away you would never get them back," she says.

"We have spent over six years in the system."

She says the professionals gave up on her and said she would never get her children back.

"After I had given up hope some other parents told me they had been able to get their kids back," she says.

"I found a professional who would work with me and helped me be a better mum.

"Against all odds I got my children back in my care and I realised how important it was for parents to hear a different story of hope and working with people who treat you like you're part of the solution not just the problem.

"We just need to empower parents instead of treating them as if they're less than human."

Families in Scotland

"Karen" is training to be a parent advocate in Scotland so she can help other families going through the system.

We can't use her real name.

She had both her children removed when they were five and six years old.

She says it was "like a death in the family with no body to mourn".

Karen believes if the right level of support had been available at the right time, she would not have lost her children.

She says: "I was battling to get my kids back and battling to keep myself together.

"I asked for support but feel like it wasn't given. They just came and whipped away my kids."

Last week, Karen, her mother and her children had their first Christmas meal at home in more than 10 years.

She says it was "amazing".

"They need to start listening to parents," she says.

"They say it's all about the kids but don't consider that we might know what our kids need and that they could put resources into supporting families to stay together rather than ripping them apart."

Reaction to figures

Dr Louise Hill, of the Centre for Excellence for Looked After Children in Scotland (CELCIS), said there could be many reasons for geographical variations in the culture and practice of those responding to the needs of children.

"It may be about what level and type of support there is on the ground and that there are different levels of investment in family support, that can have a significant impact," she said.

"Also, where there are lower levels of support in the community, we know struggling families are more likely to reach a point of crisis."

Dr Hill said some local authorities could become "risk averse" if a tragic event happened in their local authority.

Minister for children and young people Maree Todd, said she "suspected" the geographical variations in how many investigations local authorities carried out was a "data collection issue".

"We are working very hard on that in the Child Protection Improvement programme and we are keen to set a minimum dataset that is standardised throughout Scotland and we'd like to improve on that data collection.

"We recognise that's an issue."

The minister said she welcomed examples of good practice from around the world.

"While our data shows that things are going well in Scotland, we are determined to learn lessons from ourselves, from our neighbours and from anywhere in the world," she said.

"This is absolutely a key priority for us in this government. We want Scotland to be the best place in the world to grow up."