Pan Am flight 103: Finding words to describe Lockerbie tragedy

- Published

Thirty years ago, on the night Pan Am flight 103 was blown out of the sky, I drove down from Glasgow with Eddie Mair, who was then a BBC Radio Scotland presenter.

We tagged onto the back of a police convoy travelling the wrong way down the northbound carriageway of the A74 because it was blocked by debris from the crash.

Nothing could prepare you for the horror that awaited us.

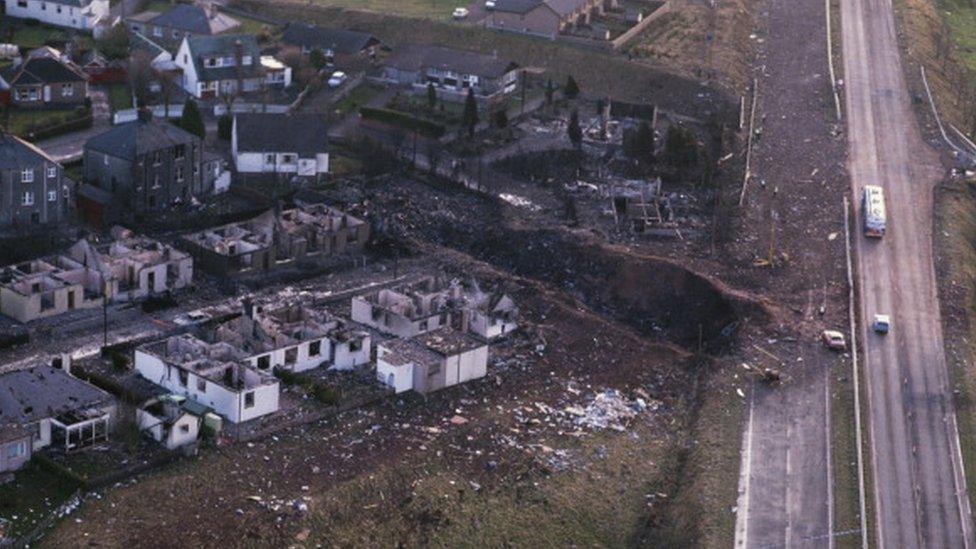

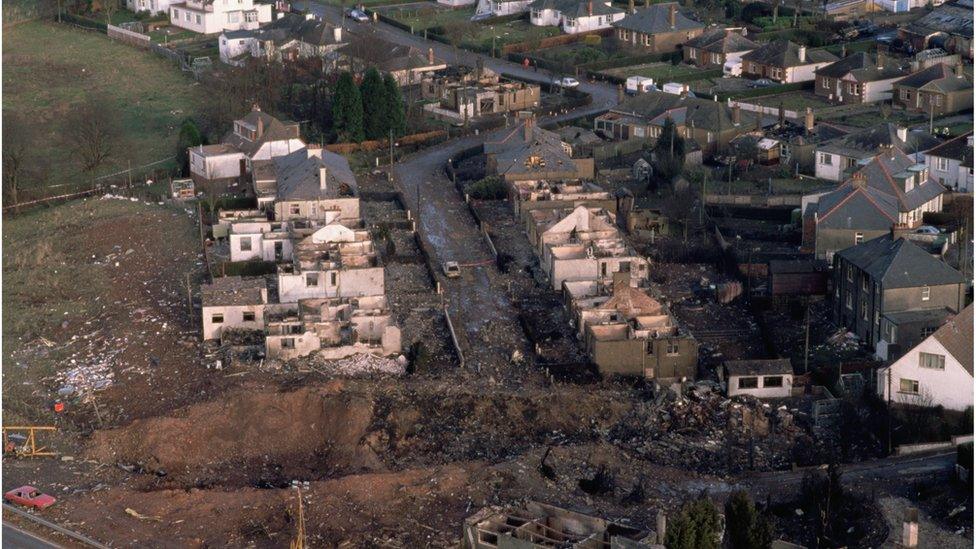

Mud and debris from a huge crater at Sherwood Crescent, caused by the fuel-laden wings of the jumbo jet, covered the southbound carriageway.

Debris from the crash covered the A74 dual carriageway

The smell of aviation fuel was heavy in the air, fire still burned, and we saw things no-one should ever have to see.

A number of burned-out houses suggested there would be fatalities on the ground as well as from the aircraft.

In the end, 11 people from Lockerbie plus the passengers and crew made a total of 270 deaths.

Ambulances began arriving but it soon became apparent there was nothing for them to do.

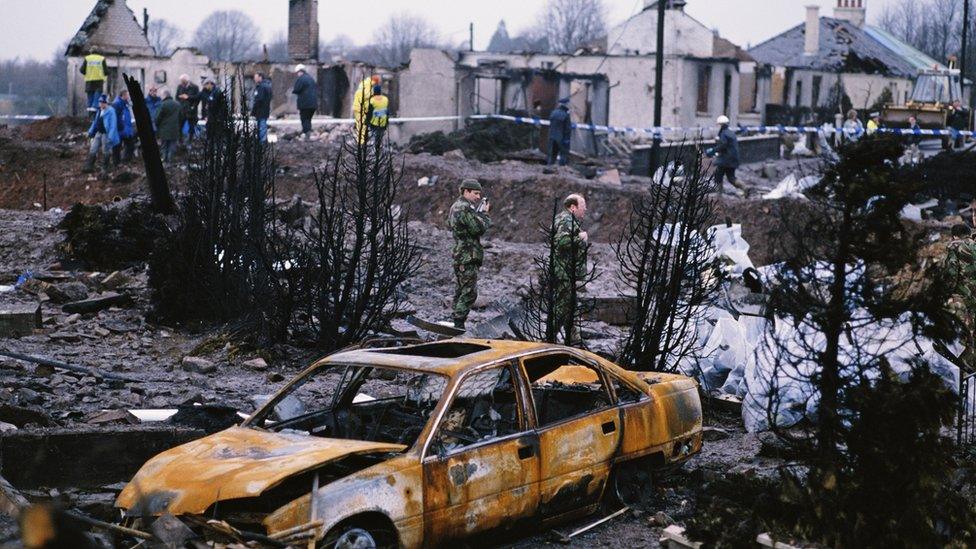

Aircraft debris and destroyed houses in Sherwood Crescent

People had either lived or died.

The next morning the cold light of day exposed the sheer scale of what had happened.

We saw the torn-off nose section by Tundergarth church.

The jet's nose came down in a field near Lockerbie

Then the enormous crater and destroyed houses at Sherwood Crescent, the demolished house on Rosebank Crescent and Sydney Place on the northern outskirts of Lockerbie.

Here a detached jet engine had fallen backwards into the tarmac feet away from some houses.

It smashed into the ground with such force it made an almost perfect circle.

What followed was a learning curve for the media.

It was about how to balance the need to report and the need for people to be left alone.

The less local the media the less understanding or concern they seemed to have in this regard.

And there was a need to learn more about Middle Eastern politics, which appeared to have been the reason for the bombing.

In those days we didn't expect it to literally explode overhead.

But one way or another, with the likes of al-Qaeda and 9/11 and Isis-inspired terror across Europe's streets, we've been living with it ever since.

Reporting terror without adding to it remains a difficult circle to square.

'Finding the words'

A few days later, the BBC's main news reader at the time, Michael Buerk, wrote a piece for the BBC in-house newspaper Ariel.

It was headlined: "Finding The Words".

And 30 years on, the bulk of a career in journalism later, finding the right words for what happened here remains a challenge.

It is also a challenge for those more directly affected.

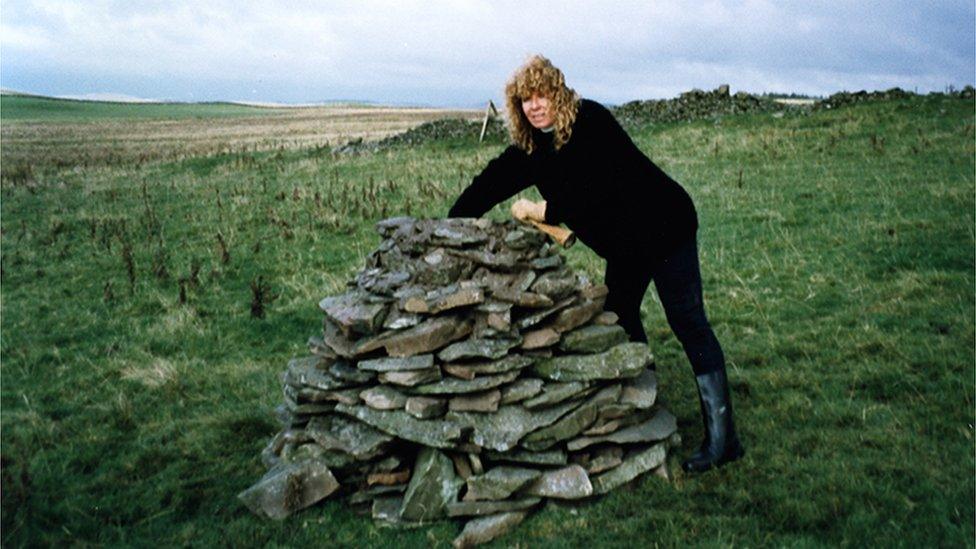

Suse Lowenstein with the cairn she built to remember her son

There are Lockerbie memorials that are well-known and others that are less so.

On one of the back fields at Tundergarth Mains Farm, about three or four miles south east of Lockerbie, there is one particular memorial.

It was built by Suse and Peter Lowenstein, from Montauk on Long Island, to mark the place where their son Alexander fell from the sky on 21 December 1988.

He was one of the 35 Syracuse University students who were on the plane and died that night.

The Lowensteins built a traditional stone cairn to mark the spot.

The wind and the elements have knocked down some of the stone cairn

It is a beautiful, peaceful setting, near Burnswark Hillfort, with just the very distant rumble of the M74 in the background.

Normally there are sheep and other animals grazing around the cairn.

The wind and the elements have knocked down some of the stone so it is slightly flattened from how it was, but it is still a noticeable reminder of something terrible which happened here.

Mrs Lowenstein wanted me to place a stone or two while I was there. So I did.

She also had one last request while I was there.

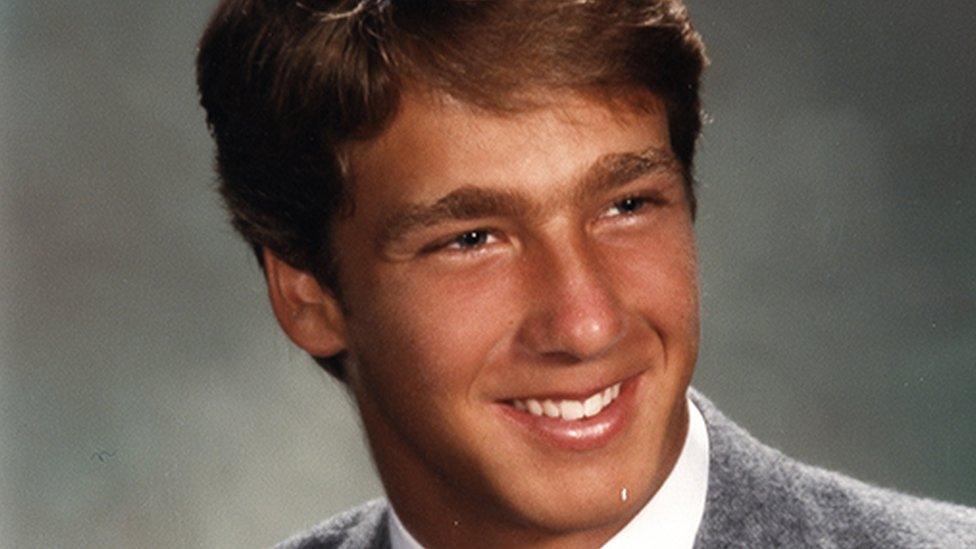

Alexander would have been 51 years old but of course his life was cut short at just 21.

Alex Lowenstein was just 21 when he died in the Lockerbie bombing

She lost her husband Peter earlier this year so this is an especially difficult anniversary as well as it being 30 years since the bombing.

She wanted me, while I was at the cairn, to tell Alexander he was a good boy.

So I did.