The 'kindness' judges turning courts inside out

- Published

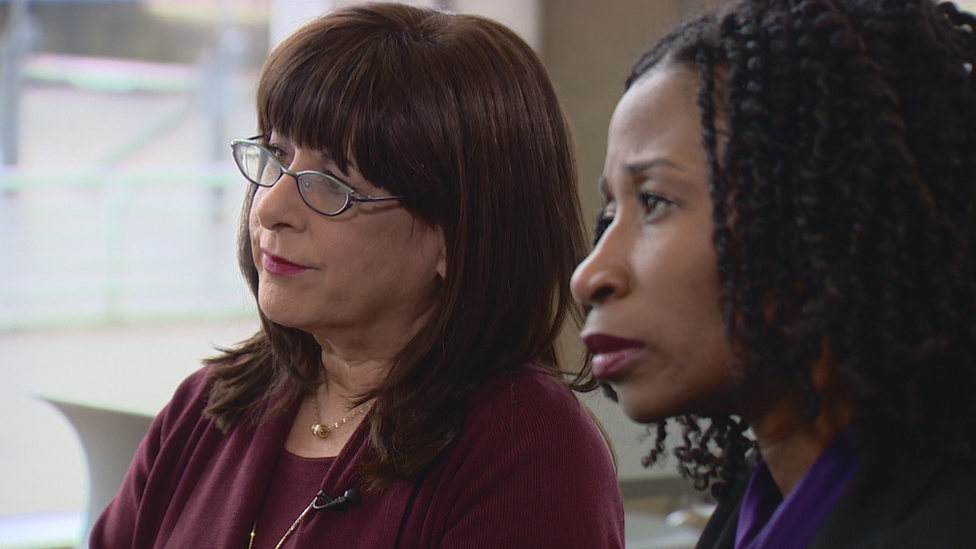

The American judges started their visit at Polmont and will meet the justice secretary

Two American judges who argue that people who come before criminal courts should be treated with more compassion and kindness have arrived in Scotland for a week-long visit.

Judge Victoria Pratt and Judge Ginger Lerner-Wren will meet hundreds of people involved in Scotland's criminal justice system.

Judge Pratt reduced re-offending in Newark by using "procedural justice".

Judge Lerner-Wren pioneered America's mental health courts.

In Florida, she set up the first mental health court in the United States, focusing on treatment rather than punishment. There are now 400 such courts worldwide.

Judge Victoria Pratt believes in procedural justice, where everyone in the system is treated with respect

They have been invited by Community Justice Scotland, a public agency which is trying to reduce offending.

The American judges visited Polmont young offenders institution and the State Hospital at Carstairs. Later this week they will meet high court judges and Scotland's Justice Secretary.

'Dignity and respect'

The concept of procedural justice is that if people before the courts perceive they are being treated fairly and with dignity and respect, they'll come to respect the courts, complete their sentences and be more likely to obey the law.

Judge Pratt said a court in New York known for its use of the approach has witnessed a 20% reduction in youth reoffending, and a 10% reduction in reoffending by adults.

"Not only does it increase the public's trust in the system, it increases compliance with orders and most importantly it increases compliance with the law," she said.

Judge Lerner-Wren set up the first mental health court in the US

Judge Lerner-Wren said her mental health court forgoes the customary formality of the courtroom.

"It's welcoming," she said. "It's like: 'I'm so happy to have you, welcome, welcome to mental health court. How can we help you? We are here to serve you'."

"It's literally taking a criminal court and turning it inside out, and instead of looking to punish, looking to help. That's the innovation of problem solving courts and the application of procedural justice.

Karyn McCluskey, chief executive of Community Justice Scotland wants judges in Scotland to know there are different ways of doing things

"It's using the authority of the judge to build that human connection and that is having a revolutionary impact on criminal justice and court process."

Karyn McCluskey, chief executive of Community Justice Scotland, said: "We've already got loads of sheriffs who're doing spectacular work in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen, and other places around this country. I just want more people to be exposed to it and realise that we can things in a different way."

One of the agency's advisors is Kathrine Mackie, who retired last year after 18 years as a sheriff, mainly in Edinburgh. She says the principles of procedural justice are already used in Scottish courts.

On her last day on the bench, she faced a repeat offender who she'd dealt with many times over the years - a single mother who was trying to overcome addiction.

Former Sheriff Kathrine Mackie showed her softer side to a woman who was trying but kept finding herself back in her courtroom

"I went and gave her a hug," she said. "I just wanted to convey to her, that I felt for her. I wanted to emphasise my confidence in her, and let her know that I felt all that for her. She burst into tears. So did my clerk."

Scottish lawyer Iain Smith is accompanying the American judges. He has written of a "degradation ceremony" in Scottish courts, "characterised by frustrated judges shouting at and humiliating broken people." He argues that "presiding with kindness" will garner respect for the judge, the courts and the law.

'Problem-solving'

Later this week Judge Pratt and Judge Lerner-Wren will attend an event hosted by Scotland's second most senior judge, the Lord Justice Clerk Lady Dorrian.

Lady Dorrian, chair of the Scottish Sentencing Council, said: "It's a concept that we are familiar with in Scotland. The difference I think is in developing particular problem-solving courts, which we have been doing also, but that's what the Americans have been doing with mental health courts, and that's what we're interested to hear from them about."