How Dutch football has tackled fan trouble

- Published

How Dutch football has tackled fan trouble

Scottish football has been engulfed in off-field controversy for what seems like most of the season, prompting calls for the governing bodies to get tough on unacceptable conduct.

Coins and bottles have been thrown at players and managers, supporters have confronted players on the touchline and sectarian singing has been highlighted once again.

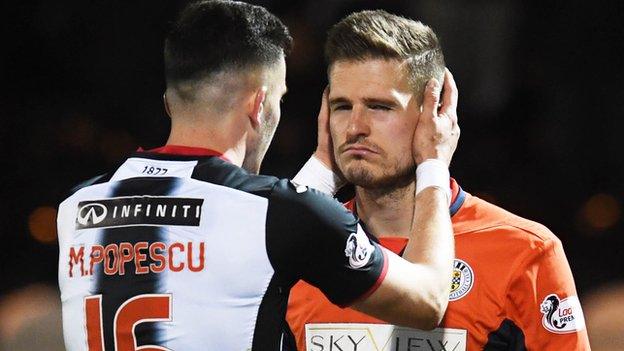

Pyrotechnics have also become a problem as an incident involving Celtic fans at St Mirren on Wednesday illustrated.

The Paisley club's goalkeeper Vaclav Hladky had to be attended to after a missile landed with a loud bang on the pitch near him.

Some believe strict liability is the answer.

This would see clubs held accountable for the behaviour of fans inside stadiums and could lead to fines, banning orders and even stadium closures - but how much of a difference would it actually make?

Dutch football has adopted its own form of strict liability for some time. It's a country with a history of fan violence and in recent years politicians there have worked closely with the Dutch FA, the KNVB, to tackle issues similar to those in Scotland.

Dutch football has introduced strict liability rules for its clubs

"They are tough. The fines are really high and I think it works," said Mike Verweij from the Dutch Telegraph.

"When Ajax played against Utrecht away there were anti-Semitic chants on the stands. Utrecht had to close the stand where it was for the next game against Ajax. Then you punish the real guys who did it, and it doesn't happen anymore."

The anti-Semitic chanting has similarities to sectarian chanting in Scotland - socially it's completely frowned upon but some fans think it's harmless for 90 minutes.

Partial stadium closures are fairly common in the Netherlands but the police believe the behaviour of fans is improving - they put that down to better intelligence and better CCTV cameras.

Stadiums in the Netherlands can be partially closed if fans misbehave

"Everything that happens in the stadium you can see on camera," said match commander Chris Koers.

"The clubs and the KNVB are very quick with fines and stadium closures. In the Johan Cruyff Arena you can see everything, you can even see the beard of someone, so you can see when they do something they are not allowed and they get fines, so it doesn't happen a lot anymore."

But if it doesn't happen much, why are fines and banning orders still issued regularly?

The SPFL is currently conducting a review of CCTV systems inside all top flight Scottish football stadia - they are also pushing for more control over football banning orders but after the failed Offensive Behaviour at Football act, politicians here seem reluctant to get involved again.

Fan behaviour is said to have improved since the rules were introduced

In 2015 the KNVB, in conjunction with the Dutch government, introduced a new improved version of something they call the Football Law. It gives greater powers to the Dutch FA, and local mayors, to ban trouble makers - not only from the grounds, but even towns where matches are taking place.

Not everyone is convinced that, or strict liability, actually works.

Criminal lawyer Christian Visser represented a number of Celtic fans who were charged following clashes with the police ahead of a game in Amsterdam in 2013. He thinks the policing and the current laws are poor.

"I think it's a bad idea," he said.

Sanction club, not supporters

He is also critical of a rule that allows clubs to pursue individual fans for the fines handed out to them by the KNVB.

"I think it could be good to sanction the club, but you shouldn't sanction the supporters via the club.

"First of all, most of the supporters who are there didn't light fireworks, didn't sing songs that shouldn't be sang. You punish people that are not involved."

It's clear that strict liability is not the panacea that some believe it could be, but some might argue that some punishment is better than nothing.

- Attribution

- Published3 April 2019

- Attribution

- Published2 April 2019

- Attribution

- Published26 March 2019