How we became part of a kidney swap chain

- Published

The Edinburgh couple who are part of a kidney transplant chain

When Mandy Murray found out she needed a new kidney her husband Graham volunteered to be a donor but was told he was not a match. Instead the couple became part of a kidney swap chain, which is allowing more people to find live donors.

Mandy first needed a kidney transplant about 19 years ago.

Because her husband was not compatible, Mandy had to wait until a suitable donation became available from a deceased donor.

She considers herself lucky to have got a phone call in the middle of the night and been rushed to hospital to receive the donor kidney.

Many people are not so fortunate. Last year, 26 people in Scotland died while waiting for a kidney transplant.

Mandy Graham had a kidney transplant from a deceased donor 19 years ago

When a person needs a new kidney they first turn to family and friends to find a living donor.

Doctors says patients who have a living kidney transplant tend to live longer and feel better than those who receive kidneys from a deceased donor.

Mandy's new kidney allowed her to function for 18 years but it has recently started to decline and she was told she would need another transplant.

Her husband Graham was tested again but was still not a match.

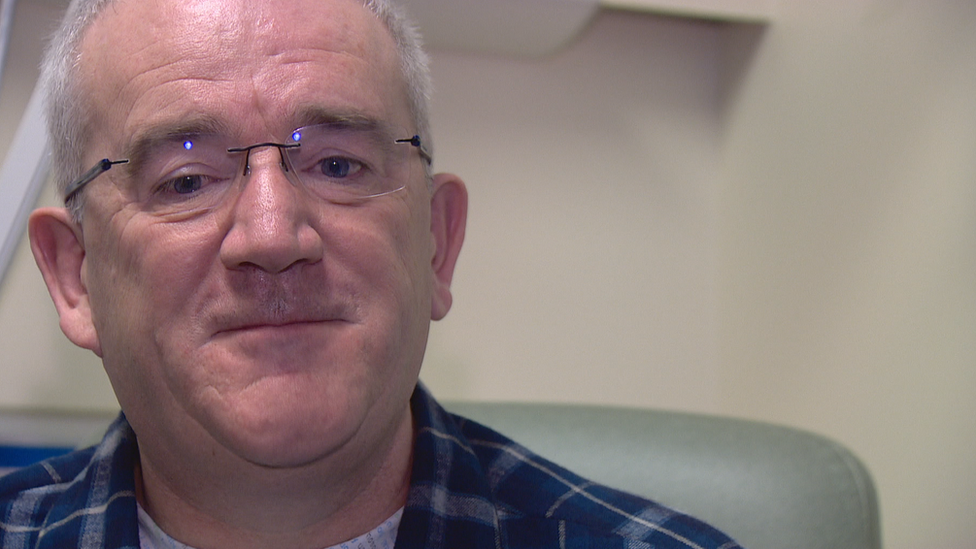

Mandy's husband Graham was not a potential donor match for his wife

However, Mandy's consultant told her about the UK Living Kidney Sharing Scheme,, external which has been running for more than a decade.

"It is where couples like us can be paired up and help each other out," says Mandy.

"My brilliant husband didn't hesitate for a moment.

"I tried desperately to talk him out of it but he was having none of it."

Computer programme

The kidney sharing scheme uses an algorithm designed at Glasgow University.

It goes through everyone who has volunteered and tries to find better matches and maximise the number of possible transplants.

The computer programme is run four times a year and the transplants are then scheduled by a dedicated coordinator.

Sarah Lundie is one of the donor scheme coordinators

It is a logistical challenge, according to Sarah Lundie, the coordinator at Edinburgh's Royal Infirmary.

In order for even the simplest kidney swap to go ahead you need two healthy donors and two recipients who are also not suffering from any illnesses.

If any one of them gets so much as a cold, the whole carefully arranged schedule must be cancelled.

Ms Lundie must also make sure that there are operating theatres booked at both locations and four surgeons must be available to carry out the procedures, not to mention their extensive back-up teams.

There is also a great deal of liaison going on to ensure that the organs are transported from the donors to the recipients at the same time.

Graham and Mandy said it was a relief to get to the day of the operation

As he sat in Edinburgh waiting to donate his kidney, Graham Murray, 53, was aware that there was someone in Belfast, who must remain anonymous, waiting to give up a kidney so that it could be donated to Mandy.

Graham says: "Getting to this morning with everyone fit and healthy and ready to go is a great relief."

His wife Mandy, 57, says they have felt the "responsibility" of keeping well in the weeks before the operations so that the donor sharing chain would not be broken.

She says: "Graham and I decided to sequester ourselves in our house, get our shopping delivered and really try not to catch anything so we could make sure that bond could be maintained."

Graham and his counterpart in Belfast are the first part of the surgical equation.

Both donor kidneys are removed simultaneously in the two locations.

In Edinburgh, consultant transplant surgeon John Terrace scrubs up for an operation he says usually takes about three hours.

Mr John Terrace, consultant transplant surgeon, RIE

"I'm thinking about the donor rather than the recipient," he says.

"The focus with donors is operating safely and meticulously. The risk to donors is actually very small."

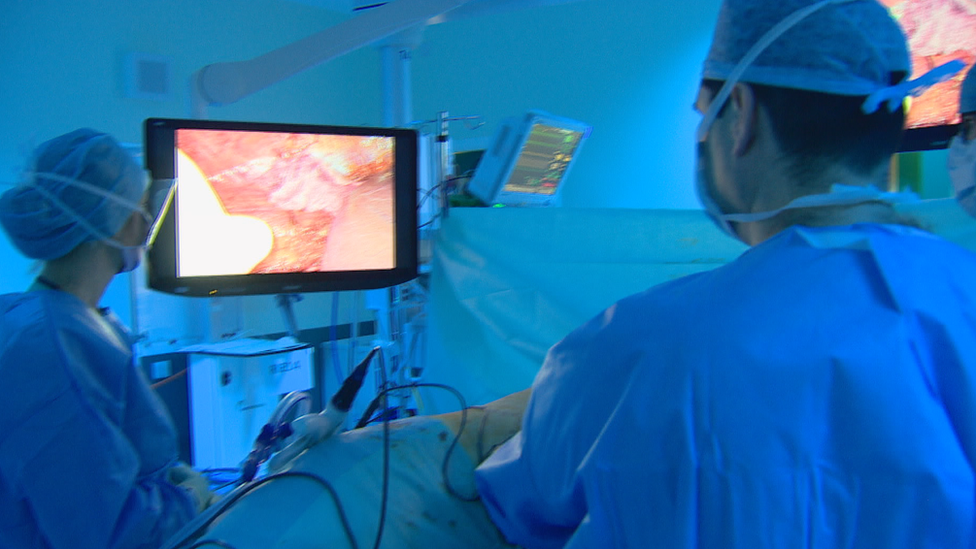

Mr Terrace says he uses a modified form of keyhole surgery to remove the kidney.

Mr Terrace uses a modified form of keyhole surgery

He uses laparoscopy to see but also has his hand inside the patient.

"That offers an extra element of control and safety," Mr Terrace says.

"The first 80% is moving things out of the way, moving the liver and the bowel and identifying the kidney and the structures that go into it and come out - the vein, the artery and ureter."

He says these are then prepared so the kidney can be removed quickly but still be suitable for "reimplantation" into the recipient.

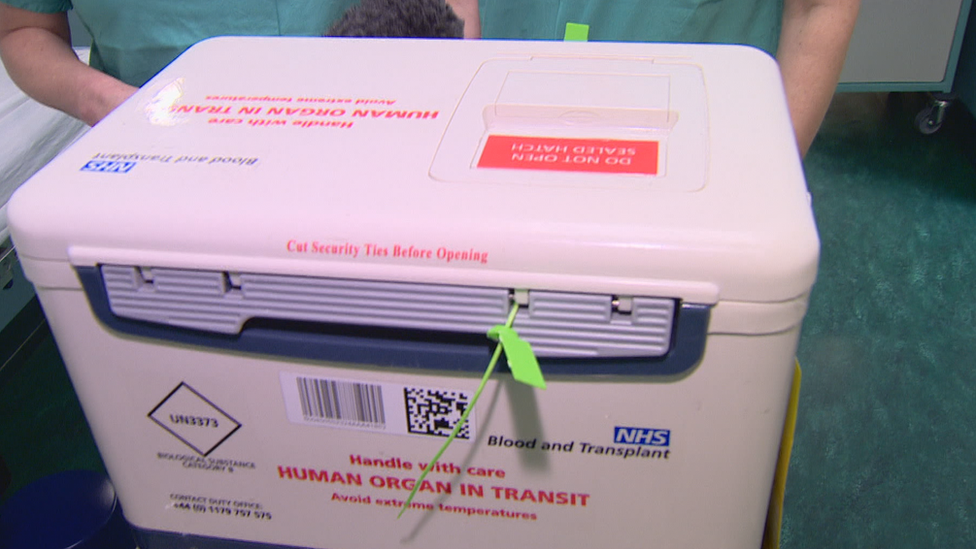

Once the kidney is removed it is quickly on its way.

In this case, the organs leave Edinburgh and Belfast on chartered flights, arriving in time for the donation surgery to happen in the afternoon.

Consultant transplant surgeon Sorina Cornateanu performed Mandy's operation

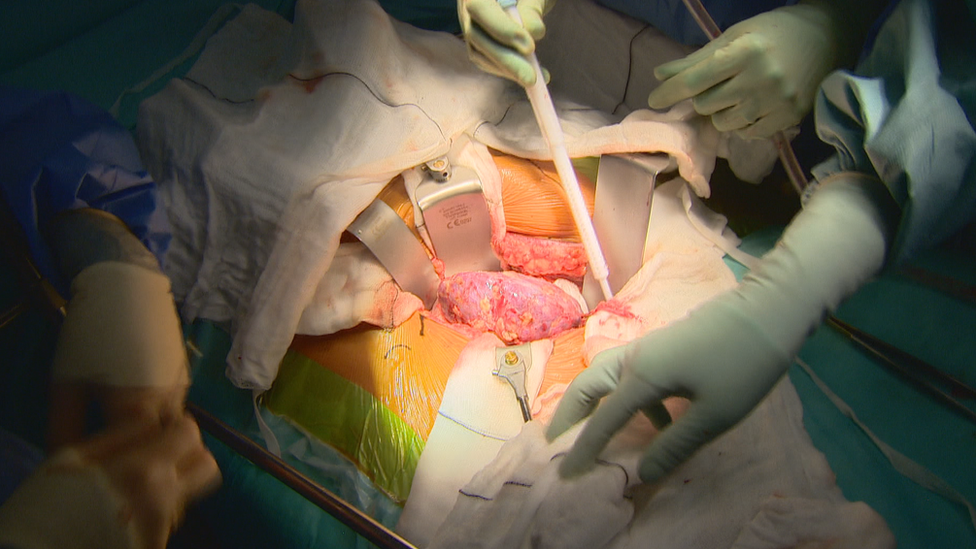

Mandy's kidney surgery is performed by consultant Sorina Cornateanu.

She uses blood vessels going to the leg to help attach the new kidney.

Then the blood supply is returned and the kidney turns pink and perfused.

Often the kidney passes urine on the operating table.

Ms Cornateanu said the shared donor scheme had been a big success

The surgery takes about three hours and the patient is immediately started on anti-rejection drugs and goes into a high-dependency unit.

After successfully operating on Mandy, Ms Cornateanu describes her team as the "vehicles" between the donor and the recipient.

"That's our role. It is fulfilling, rewarding, humbling and it is a big relief at this stage."

Ms Cornateanu said the shared donor scheme had been a big success and even in the past year the number of live donor transplants had risen in Edinburgh by half to 14.

"It has been a big team effort from all of us and we need to sustain that. That's the challenge."

Living donors

Across Scotland, 50 kidney sharing scheme transplants have taken place in the past five years.

It is more common for living donor transplants to involve a relative or friend who is a close match but this is not always possible.

Another form of living donation is "altruistic". Over the past 10 years, 78 people in Scotland have donated a kidney to a stranger.

The day after their operations, Mandy and Graham were told the other donor and recipient in the chain were doing well.

Graham said: "That's fantastic. We never expected to know."

"I'm so pleased," said Mandy.

The pair hope they will soon be recovered enough to fulfil all the plans they have had to put on hold until now.