Scotland's role in the D-Day landings

- Published

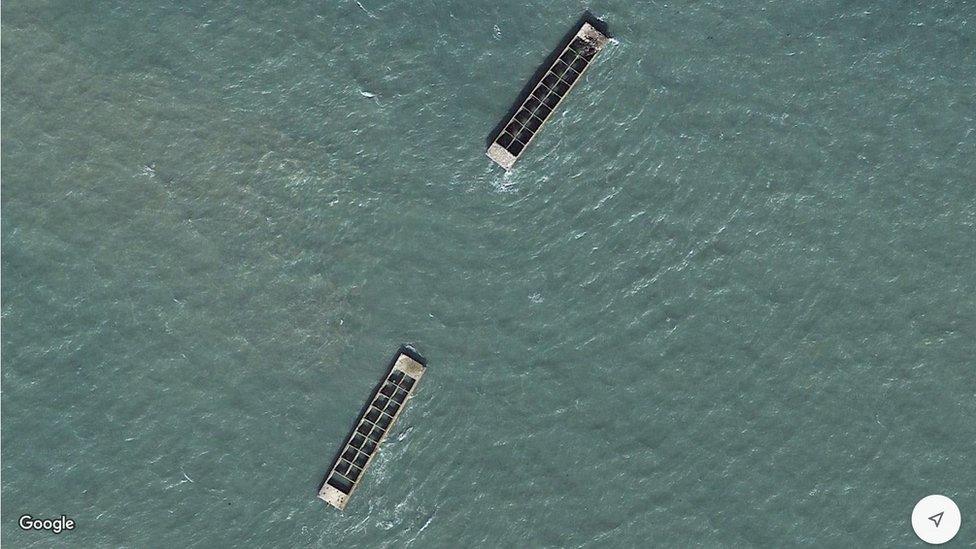

Pontoons from the Mulberry Harbour can still be seen at Arromanches in Normandy

In Garlieston village hall there is a small exhibition telling how it played an important role in the run-up to the D-Day landings 75 years ago.

On 6 June 1944, Allied forces began to land thousands of troops on the beaches of Normandy in France, laying the foundations for victory in World War Two.

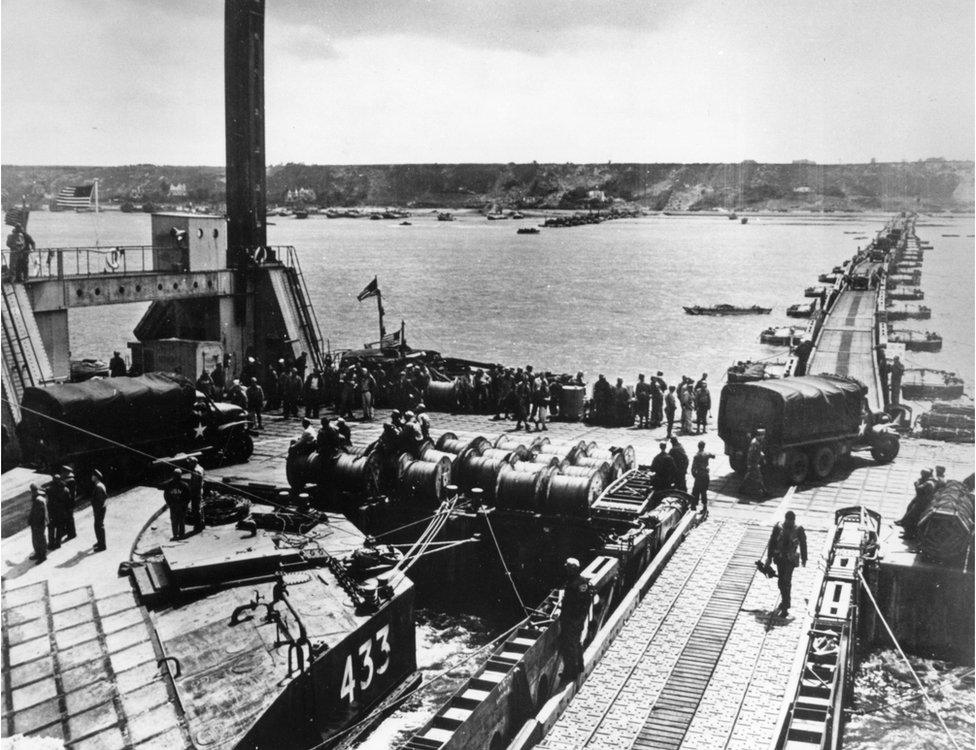

In order to be able to get supplies and other materials ashore after the landings the military had been secretly planning, testing and developing a system of temporary portable harbours.

The American Mulberry Harbour was destroyed by storms

In the months before D-Day, Garlieston, in south west Scotland, was chosen as the perfect place to carry out the tests.

It tried out three prototypes: one called the Hippo, one called the Swiss Roll, and prototype 3, the Spud pier and Whale roadway - which was to become the Mulberry Harbour.

The bays around Garlieston were chosen to test the harbour systems

During the first phase of the D-Day landings, the flat sandy beaches of Normandy were perfect for troop-carrying landing craft.

But the Allies needed a port to hold the beachhead after the initial invasion and allow the unloading of larger troopships and supply vessels.

Because the Germans would strongly defend any conventional harbour, such as Le Havre, the Allies decided to take their own.

Consisting of concrete docks and roadways floating on pontoons to the shore, Mulberry Harbours were simple but revolutionary, creating a port the size of Dover.

Beetle pontoon at Portyerrock bay near Garlieston

Local historian Roy Walter feels Garlieston's role in the Normandy invasion has been rather overlooked.

He has put together an exhibition for the 75th anniversary of D-Day to help people find out about a largely forgotten part of Scotland's wartime history.

Mr Walter says: "There were three prototypes tested here and two of them were quickly discounted.

"That left the one that was finally worked up to production.

Mr Walter says the 400 harbour sections were produced all over the UK from Glasgow down to the south coast of England.

They were then towed over to Arromanches in the days after D-Day and assembled on the French side of the channel.

Willie Drynan lived in the town and worked on the project

Willie Drynan worked at a local saw mill in Garlieston when he got his call up papers in 1943.

But instead of heading south for training and possible deployment in the front line he was told to stay put and was assigned to the top secret Mulberry Harbour project.

Willie, who will be 100 years old later this year, remembers it all well.

When did he realise what he was working on?

"Well, with a bit of common sense you could see the pontoons and bridge section between them.

"They took them out into the bay every day for a measured mile to get the speed and how fast they could pull them between here and France."

The remnants of the concrete breakwaters to protect the Mulberry Harbour at Arromanches are still there, visible on Google satellite images.

Willie Drynan says he can hardly believe it.

Retired farmer Tom McCreath remembers seeing the harbours being tried out

Retired farmer Tom McCreath, who has co-authored a book about the time, remembers seeing the harbours being tried out when he was a teenager.

"The first thing I remember was a huge amount of military activity and things floating all around Garlieston harbour," he says.

"Locally people saw it but the military made it quite plain it wasn't to be talked about."

Mr McCreath said it was after the landings in Normandy that he discovered what the harbour had actually been used for.

On Rigg Beach in Garlieston, time and tide have taken their toll so not a lot still remains of the secret wartime project.

But you can see the bits called beetles that supported the floating roadways.

And there is also something that looks like a bit of a castle but is actually a 5-metre-high structure designed to replicate a cliff.

Local historian Roy Walter at the remains of a "cliff" that was part of the tests

It was part of the experiment which didn't work.

They are listed as national monuments by Historic Scotland.

Local historian Roy Walter says: "This type of archaeology is very much at risk from the sea. It means, being listed, that they actually get some attention from the national bodies that preserve these things."

A couple of miles down the coast is Cairnhead Bay, where the Mulberry Harbour eventually used at Arromanches was tested - and it proved the most crucial of the two such harbours deployed around D-Day.

Because of the worst Atlantic storm for 40 years, the American Mulberry Harbour was destroyed and only the British one survived for any length of time.

In the 10 months after D-Day, it landed more than 2.5 million soldiers, half a million vehicles, and four million tonnes of supplies.

Garlieston on the Solway Firth might be a small place but it played a big role in winning the war.