Laser drones protect Scottish forests

- Published

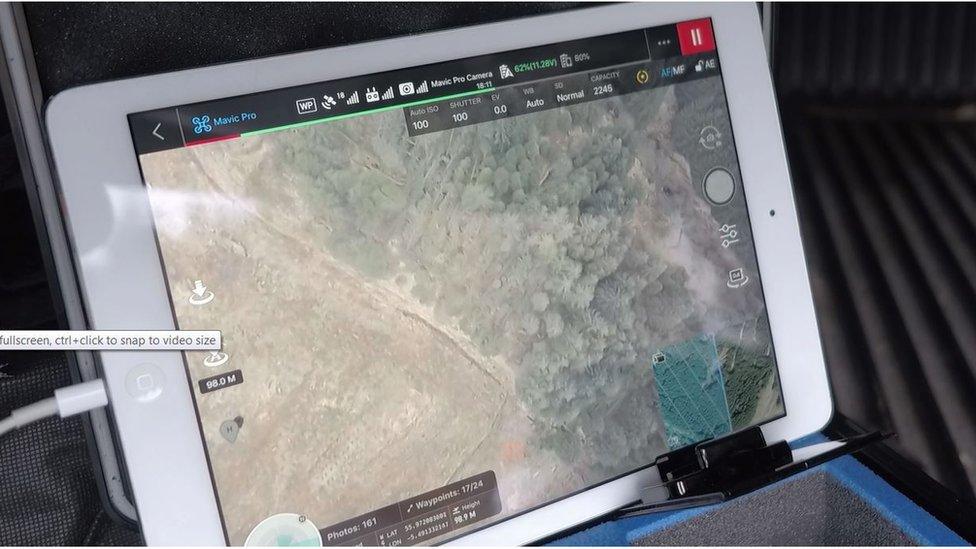

Information from the drones can be used to see the vegetation beneath the forest canopy

Laser-carrying drones that can see through the forest canopy are being used to protect native Scottish plants threatened by invasive species.

The drones use Lidar (light detection and ranging), which works like radar but uses light instead of radio waves.

Laser pulses are fired at the trees below and the time it takes for wavelengths to bounce back is used to create a 3D picture of what lies beneath.

The data is combined with information from satellites to give an accurate "fix" of the drone's position.

It all builds up an accurate map of the health of the forest floor.

The drones use Lidar (light detection and ranging)

The programme is led by the Edinburgh-based company Ecometrica.

Its funding partners are the Forestry Commission Scotland, Scottish Orienteering, Woodland Trust and Edinburgh University.

Support has also come from the UK's Science and Technology Facilities Council.

Once it is in the air, the four-rotor drone is easier to hear than see. It is a speck in the sky but packed with sensors.

It has been surveying forests in the west of Scotland: Lochgilphead, Ardfern, Auchterawe, Arisaig, Achdalieu and Mandally.

The drone has been used to survey forests in the west of Scotland

Lidar has been used from the air before but typically this has been from larger aircraft with humans on board.

An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), usually known as a drone, holds out the prospect of reduced cost.

The point of the project is to monitor and map how land use is changing and how climate change is affecting Scotland's forests.

Conventional photos taken in natural light will only show the tree canopy.

And as much of the tree cover is evergreen and there all year round, there's no point waiting for autumn to have a look beneath it.

Better resolution

Ecometrica's executive chairman Richard Tipper says the technique offers "centimetre-scale detail".

"It enables you to pick out features that a satellite doesn't allow you to do," he says.

Large-scale global deforestation is being monitored from the International Space Station by the GEDI Lidar system.

Dr Tipper says a Lidar drone covers a much smaller area with each sweep but the resolution is "an order of magnitude better".

One key emphasis is on protecting native species - and fighting one non-native threat in particular.

Rhododendron bushes like Scotland a bit too much

Back in the 1700s it seemed like a good idea to introduce the flowering shrub rhododendron ponticum, a native of southern Europe and western Asia, to the British Isles.

After all, their purple blooms look lovely in early summer.

The problem is, the rhododendron bushes like Scottish forests rather too much.

The acid soil means they have spread like a smothering evergreen carpet beneath the cover of the tree canopy.

You could say it is a case of having too much of a good thing except they're actually a bad thing.

They carry a fungal disease that harms trees and their leaf litter is toxic to native plants.

Without Lidar the bushes can spread undetected.

The drone data is analysed using a system called Ecometrica Platform

The drone data is analysed using a system called Ecometrica Platform. It creates the detailed maps that show changes to the ecosystem.

Each partner in the project has a different use for the information.

The Forestry Commission is concerned with rhododendrons but The Woodland Trust wants to map the remains of native forests.

Edinburgh University will feed it into new research, and Scottish Orienteering need digital models of the terrain as Scotland prepares to host the World Orienteering Championships in 2022.

More depth

Mat Williams, professor of global change ecology at Edinburgh University, says the system can play an important role in assessing the effects of climate change.

He says it can detect the effects of human land use, deforestation, soil degradation, forest fires and drought.

And Scotland is a testbed for technology that could be used worldwide.

Ecometrica are also leading Forests 2020, a UK Space Agency-funded programme to map threats to tropical forests.

Prof Williams says his team are exploring the data gathered in Scotland to see how the techniques could be used there.

"For a long time we've only been able to look at the surface of tropical forests," he says.

"We're hoping Lidar can look in more depth."

Taste for chocolate

Among the answers they are seeking is how many - or how few - Lidar pulses bouncing back from the forest can provide useful information.

They intend to begin flying Lidar drones in West Africa soon.

Among the threats there are illegal logging, charcoal burning and our apparently insatiable taste for chocolate.

Ecometrica's space programme manager Sarah Middlemiss says the project is working with the forestry authorities in Ghana to map the felling of trees in national parks to make way for cocoa.

She says cocoa plants can encroach on the forests even if they are not completely cut down.

"It's a shade-loving crop," she says. "That's where Lidar is very useful."

Cocoa crops can grow beneath the forest canopy but the technology will be able to reveal them through the foliage.

"You can't map everything from satellites," Sarah says.

"We need other data sources and Lidar is about the richest you can get."

- Published10 May 2019