Atlantic Ocean 'running out of breath'

- Published

'Safe havens' for marine life will be identified in the ecosystem of the Atlantic Ocean

A huge international research programme has been launched to assess the health of the Atlantic Ocean.

The iAtlantic project is the biggest ever mounted in the planet's second largest ocean.

It involves more than 30 partners, funded by the EU, and is being co-ordinated by Edinburgh University.

The scientists will use an array of hi-tech devices, including robot submarines, to scan the deep ocean from the Arctic to South America.

They want to assess the effects of climate change on plants and animals.

They will use genomics, physics, machine learning and other specialisms, and spend four years creating a digital map of the ocean's ecosystems.

A remotely-operated underwater vehicle is used to gather footage of the coral mounds of the Mingulay reef off the west coast of Scotland

The project will look at all aspects of life in the Atlantic Ocean

The results will help governments decide which developments of the Atlantic are sustainable and responsible.

They will also highlight "refuges" where threatened species may have a chance to survive.

The Atlantic is suffering from a three-pronged attack, according to iAtlantic programme co-ordinator, Prof Murray Roberts of Edinburgh University.

By way of illustration, he opens a sample bucket and pulls out a deep-sea red crab about a foot across.

He's a beauty. He's also quite dead, sampled in 2012 and submerged in preservative ever since.

"It's just to give you an idea of how big and beautiful the life of the deep sea is out there," the professor says.

The world's oceans have absorbed most of the effects of global warming and researchers want to understand the impact this is having on plants and animals

From other buckets he pulls specimens of black coral and a deep sea skate's egg case, a large version of what we landlubbers sometimes refer to as a mermaid's purse.

So far, so diverse. So what's the problem?

"What will happen to these animals in the future as the Atlantic changes?" Prof Roberts says.

"As it gets warmer, as it gets more acidic and also - in some areas - as it runs out of breath.

"Because the Atlantic, like many ocean basins in the world, is being deoxygenated - it's losing the oxygen that is vital to life."

The cause is climate change, 90% of the world's global warming has been absorbed by the oceans.

All forms of ocean life, from whales to plankton, will be assessed by the scientists working on the project

The team will be focusing on the ecosystems of 12 areas, including the Mid-Atlantic Ridge off Iceland, the Sargasso Sea, the cold deep from Angola to the Congo Lobe and the Vitória-Trindade Seamount Chain off Brazil.

Plus, much closer to home, a coral reef just off the Western Isles.

In the lab in Edinburgh, Dr Laurence De Clippele shows us underwater camera footage of the coral mounds of the Mingulay reef.

The images are remarkable but technology allows her to do more.

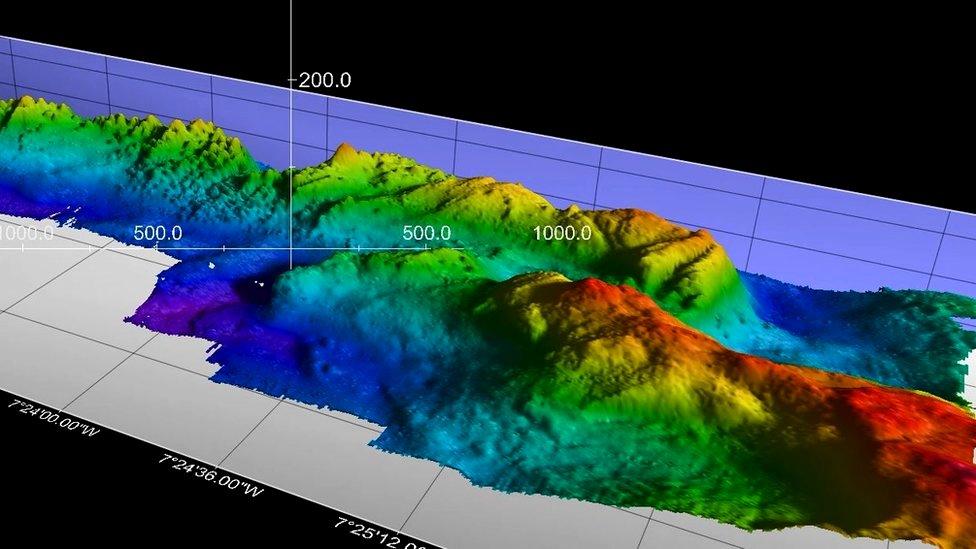

The mounds have been mapped in unprecedented detail by a remote-controlled submersible equipped with sonar.

The coral mounds are shown in a 3D map

Dr De Clippele has transformed the data into strikingly-coloured 3D maps.

It is one of the technologies the iAtlantic team hopes to apply to the whole ocean.

"You can see all these little lumps here. They are live coral," she says.

"The mounds consist of both dead skeletons - calcium carbonate - and live."

Typically, we onshore encounter calcium carbonate as chalk. But it also makes up the shells of marine organisms.

If the acidity of the ocean reaches a high enough level, it will be extremely bad news as the shells may soften or dissolve completely.

What's more, if a coral does not respond well to rising sea temperatures it is not in a position to up sticks and move somewhere else.

Scotland's only inshore coral reef, the Mingulay, in the Western Isles will be part of the study

"These reefs are very important because they provide a home for many animals," Dr De Clippele says.

"They can shelter there, feed there, reproduce there."

"And some of them are economically important because they might end up on our plate."

Another of the partners is the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS), based at Dunstaffnage near Oban.

There, on the shore, physicist Prof Stuart Cunningham shows me an autonomous glider.

The impact of warmer sea temperatures and greater acidification will be the focus of the study

Looking for all the world like a torpedo with wings, it can vary its buoyancy to glide a kilometre below the surface of the ocean to take measurements, then "fly" back to the surface to send the data home via satellite.

It does it unassisted for up to six months at a time.

"We can measure properties like temperature, salinity, currents and oxygen," Prof Cunningham says.

"As well as other parameters like how much of the sunlight is penetrating into the ocean."

'Real problem'

The project will last four years, with the European Union's Horizon 2020 programme putting in more than €10m.

Another €30m will be coming from partners in the form of research cruises and other technologies.

Prof Roberts says they will examine all aspects of life in the ocean column.

"We'll be looking at humpbacks, we'll be looking at plankton, we'll be looking at corals," he says.

"And then we'll be working in terms of how the physics of the ocean is changing.

"We can then understand where the ecosystems are tipping from one state into another, where we're going to have a real problem in the future.

"If we can identify those areas then we can then work with governments to back off the pressure."