Smart sensors listen to healing wounds

- Published

The new technique means a patient's bandages do not have to be removed to see what is happening with the wound

A new technique is being developed to help heal wounds by listening to them.

Researchers at Heriot-Watt University are creating tiny electronic sensors that can hear what is going on below the bandages.

Wound care costs the UK's health services billions of pounds a year.

While some types of specialist wound dressings are available, the principal method of finding out how well a wound is healing has been to remove the bandages and take a look.

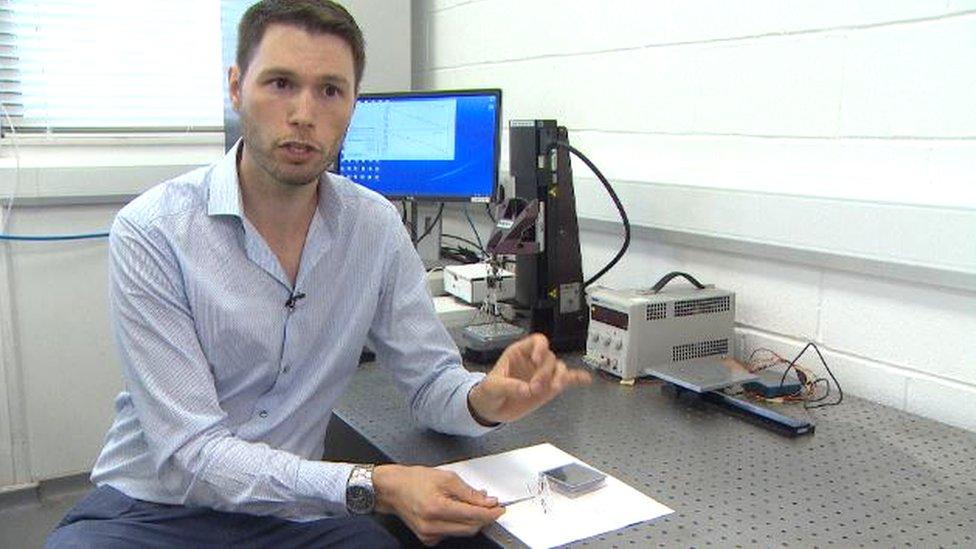

The team is led by Dr Michael Crichton, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Heriot-Watt.

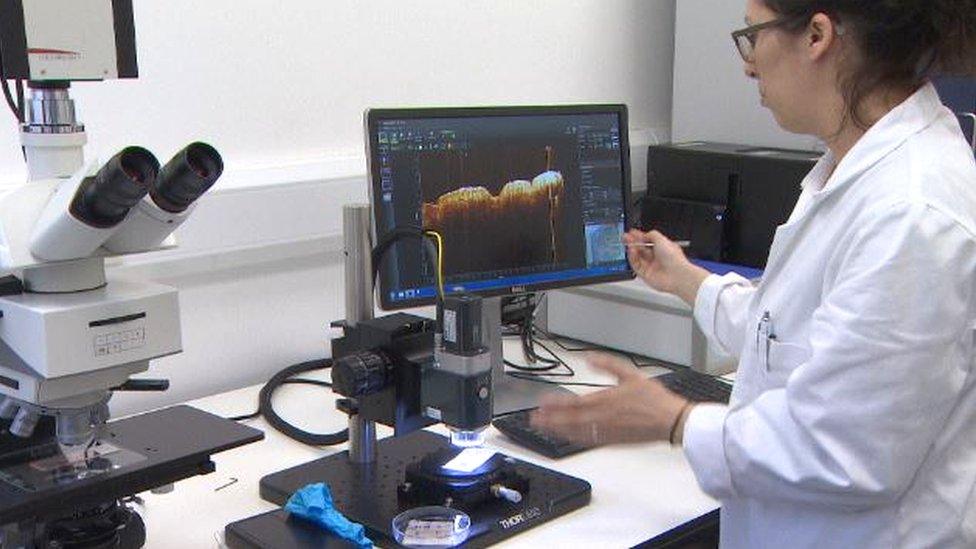

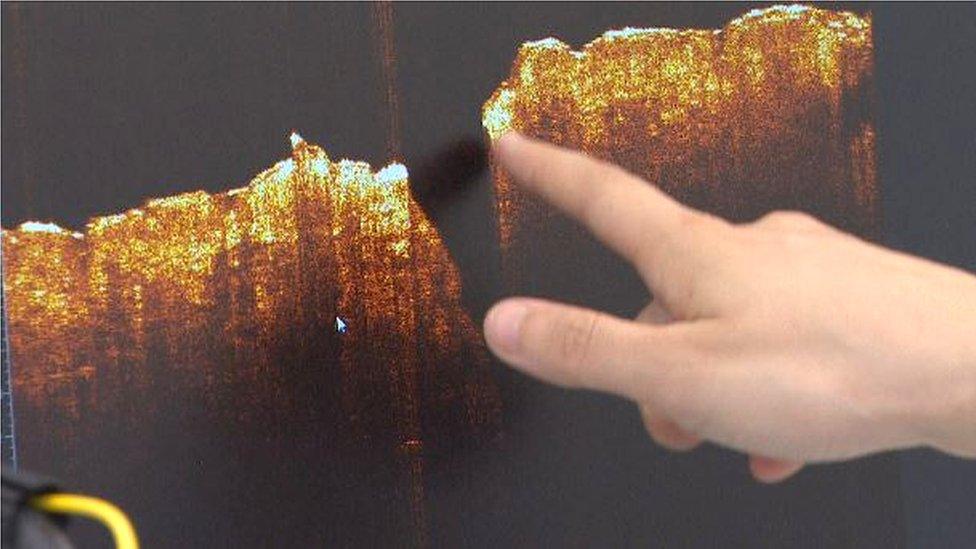

3D images of the injury can be created

He says he wants to bring data into the process. "If we can put a sensor on the surface of the tissue, around a wound or across a wound, can we actually measure what's happening?

"If we can do that, that will tell us if a wound is likely to be going in one way or another.

"And if we can measure it over time, then we don't need to keep on opening up a wound and saying, 'is it getting better or is it getting worse?'."

But what does a healthy wound sound like? Before they can know that, the researchers must investigate how skin behaves when it is cut.

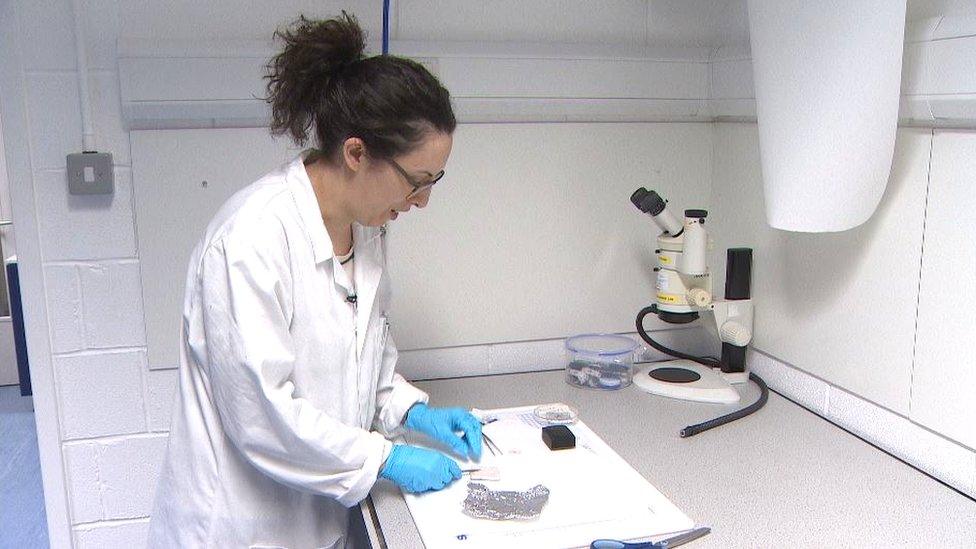

Which is why doctoral student Sara Medina Lombardero is carefully shaving a layer of fat from a skin sample.

Studying tiny shavings of skin shows how the tissues are reacting

It is freshly-sourced pigskin, a suitable analogue for human tissue.

"My part of the project...is to know how each layer of skin contributes to its mechanical properties," she says.

She cuts the skin into carefully measured strips, then makes a tiny incision in one of them.

She places the sample under the gaze of a sophisticated imaging device - an optical coherence tomography system - which produces detailed 3D images of the skin's structure below the surface.

The research team has been able to see how a wound is healing

Will we be able to see the tiny cut?

"There it is," she says.

"I can tell from this image that it is actually going through all the layers."

There are so many different kinds of wounds to be healed.

Accidents, surgery, bedsores all present different challenges. Some wounds become chronic.

Even a tiny cut on the fragile skin of an older person can become infected and in some cases can require a limb to be amputated.

Listening to the body's tissues on a microscopic level could yield new approaches. But that requires sensors operating on the same scale.

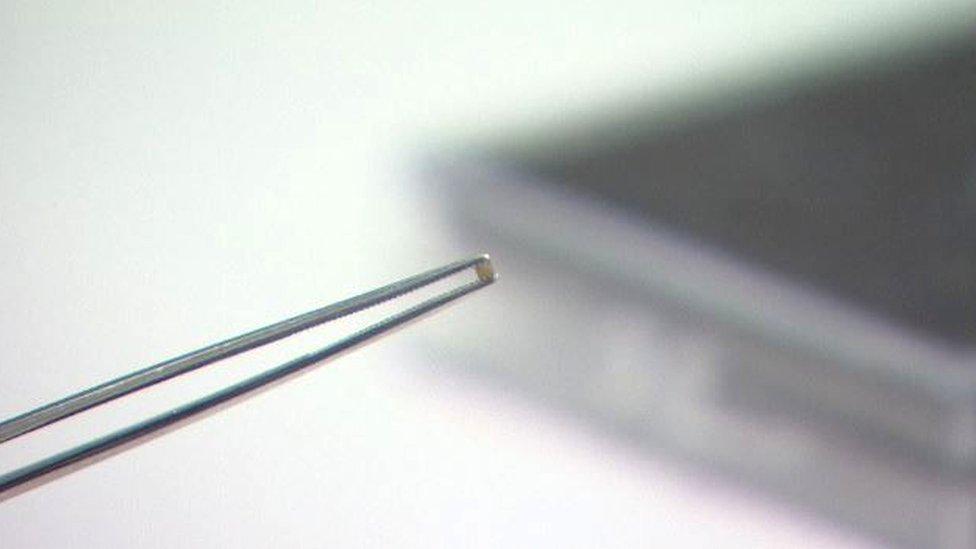

To give us an idea, Dr Crichton uses tweezers to hold up a speck not much larger than a grain of sugar.

The tiny sensor tracks how sound moves through the tissue

A sensor this size must be able to transmit sound as well as receive it.

"What we want to do is basically take little components that are going to vibrate and transmit little waves," he says.

"Ultimately it's a case of...allowing that sound to transfer through the tissue.

"We'll get an indication of how quickly the sound is transmitted, and that will give us an idea of the strength of the tissue underneath."

The two-year project is being supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

Dr Crichton wants to bring data into the healing process

The team's multidisciplinary approach involves Dr Jenna Cash, a specialist in wound healing immunology at Edinburgh University.

"Our work on the immunological response during healing is reflected in mechanical changes," she says.

"Anything that combines these has the potential for new therapies."

This may be true of more than wounds.

The treatment of damaged organs and cancers may one day also be helped by science's ability to eavesdrop on our bodies.