What Spain can teach Scotland about organ donation

- Published

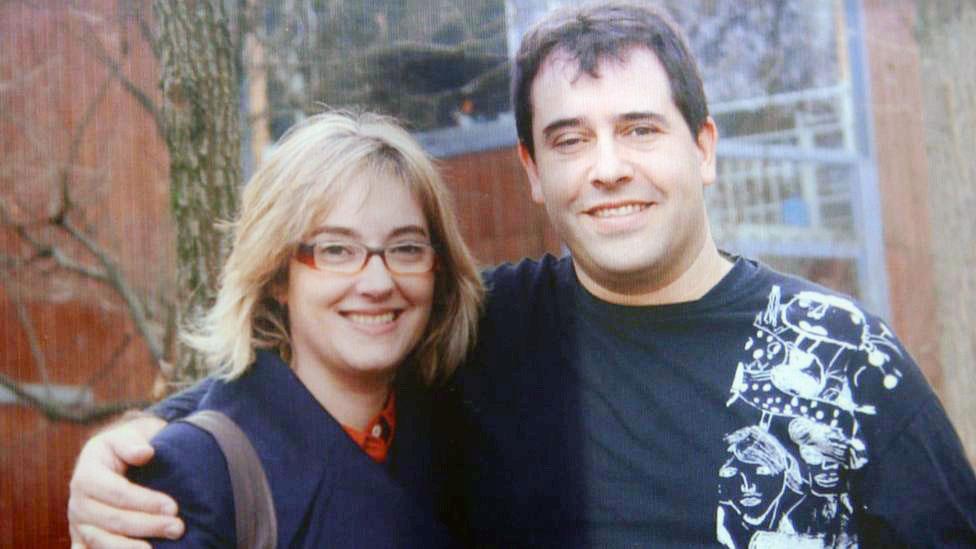

The organs of Gemma Catalá's late husband, Jordi, have been given to three other patients

From next year the organ donation system in Scotland is changing. Under the new "opt-out" regime, it will be assumed that people want to donate their organs for transplants after they die, unless they have stated otherwise. BBC Scotland's The Nine has been to see how a similar scheme in Spain works.

The doctors and nurses in the gleaming new intensive care unit at Vall d'Hebron hospital are focused on their duties, but they are happy for us to film them at work.

They're rightly proud of the care they give some of the most seriously ill patients in Barcelona.

But while we're there the relaxed mood suddenly changes and we are ushered out of the area quickly.

Along the corridor a young woman breaks down in tears as the doctors explain her mother will never wake up after suffering a stroke.

It is a reminder that every story of a life saved by organ transplant must begin with a heartbreaking moment.

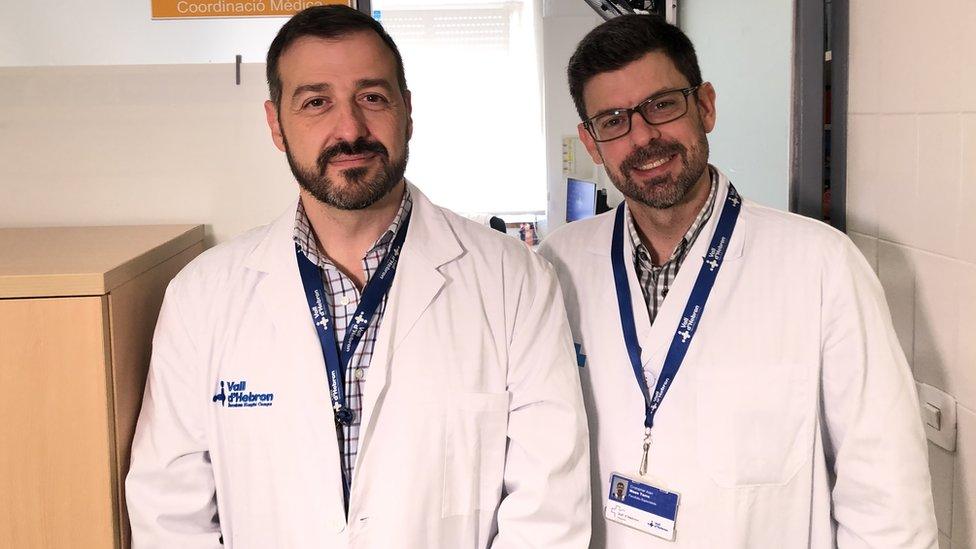

Dr Alberto Sandiumenge and Dr Cristopher Mazo work at Vall d'Hebron hospital

In 1979 Spain moved to a "soft opt-out" organ donor register, similar to the one that will come into effect in Scotland and England from 2020.

It means that when someone dies, it is presumed they want to donate their organs - unless they have actively opted out of the system. But the approval of their family is also required.

In the UK, it is hoped this will increase the number of organs available for life-saving transplants but in Spain there was no significant increase in donations for a decade after the law changed.

Thirty years on the country's organ donation rates are the highest in the world and the number of donors per million of population is about 48.

This is double the UK figure and compares with 18 in Scotland last year.

Dr Ernest Hidalgo is a liver transplant surgeon who was based in Edinburgh for several years

Vall d'Hebron has pioneered the role of specialist doctors in promoting high levels of organ donation.

In the corridors of the intensive care unit, as the woman's family is learning of her death, Dr Alberto Sandiumenge talks to the doctor who treated her about her suitability as a donor.

Organ donation in the UK is largely co-ordinated by specialist nurses but Dr Sandiumenge is a fully qualified intensive care physician, as well as a transplant co-ordinator.

He told BBC Scotland's The Nine: "Being a doctor allows me to talk as an equal with the treating physician."

They call it "active detection" - moving from the trauma ward, to accident and emergency, to intensive care, constantly monitoring which patients might become potential donors.

Staff are trained to monitor which patients might become potential donors

Gemma Catalá was returning to the hospital for the first time since her husband, Jordi, died suddenly from a brain haemorrhage. He was 50.

She believes he would have wanted to be a donor.

She said: "My husband always said we should help other people. He was a very generous person.

"He used to tell me that when you die you disappear, so why don't we help other people?"

She says it helped her and her teenage sons to know that Jordi's death had allowed others to live.

"That's the first thing I thought - let's learn something from this misfortune, and that's what I told my kids.

"In that moment if I could have done something for my husband, and we had got an organ [from a donor], I would have accepted it.

"That's why I told my kids, in this moment, your dad is going to make some other families happy."

Jordi's organs went on to be given to three other patients.

Dr Teresa Pont said nearly 350 transplants were performed at the hospital last year

For Dr Christopher Mazo, Dr Sandiumenge and their colleagues, the underlying principle of an opt-out system changes the nature of each conversation with a bereaved family member.

Dr Sandiumenge said: "We ask the family if they have any knowledge of their relative opposing to donation.

"More often, when we talk about organ donation, in the worst possible situation when their relative has just died, they actually approach the subject in a completely spontaneous way.

"They say, do you think he could be a donor? Do you think he can help others? So they approach the subject before we do."

But doctors involved in the so-called Spanish model seem convinced that a change in the law is not enough alone.

'Trust in the system'

Dr Teresa Pont has been working at Vall d'Hebron since the national system in Spain was set up.

Thirty years ago, the annual number of transplants performed at the hospital was around 80 or 90. Last year it was nearly 350.

Dr Pont, who is now the director of the transplant team, said there are many factors in the success of the Spanish model, from the opt-out system to continuous training of the doctors and nurses in every hospital.

She added: "It is all of these factors together. But the important thing is that it starts in the hospital; that the transplant co-ordinator is in the hospital and knows the position of the different patients.

"The law is a cover but it's not enough, because it's a soft opt-out system. We interview every family to know the will of the specific patients. And then the important thing is that the family has trust in the system and trust in the doctors."

Francesc Sala received a liver transplant at Vall d'Hebron in 2018. He said: "When I die, I am going to be a donor as well."

One of Spain's achievements is translating a greater number of patients who meet initial organ donation criteria into actual donors.

But that's a complex task. Last year in Scotland, 420 patients could have been considered eligible. Of those, 228 of their families were approached for consent, and ultimately only 98 became actual donors.

A Scottish government spokeswoman said: "Organ and tissue donation can be a life-changing gift and the introduction of an opt-out system in autumn 2020 provides further opportunities to save and improve lives.

"The new system will add to the package of measures already in place that have led to significant increases in donation and transplantation over the last decade."

'Proud and relieved'

Following up with the families of donors is the final piece of the jigsaw for Dr Sandiumenge and the team at Vall d'Hebron.

He said: "We call them one month after the transplantation process has passed, to tell them how the recipients are.

"They are so proud and relieved, and I'm sure it helps them with the grieving process."

Gemma Catalá agrees that thinking of Jordi's gift to others has helped her to believe that he lives on.

She said: "It's a way I use to imagine my husband, part of him, is still alive in other people."

- Published1 February 2019

- Published1 August 2018

- Published11 June 2018

- Published10 September 2017