Football star Rose Reilly among women donating brains for study

- Published

Rose Reilly has been inducted into the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame

Trailblazing footballer Rose Reilly has pledged to donate her brain after her death so more research can be done into female concussion.

Rose, who was crowned the world's best female footballer in 1984, said she knew former players who had died of degenerative brain conditions.

The 64-year-old, from Stewarton in Ayrshire, said: "We have to have more information about these things for the future generations."

Experts at Glasgow University are at the forefront of work to try to learn more about the effects of brain injuries on women.

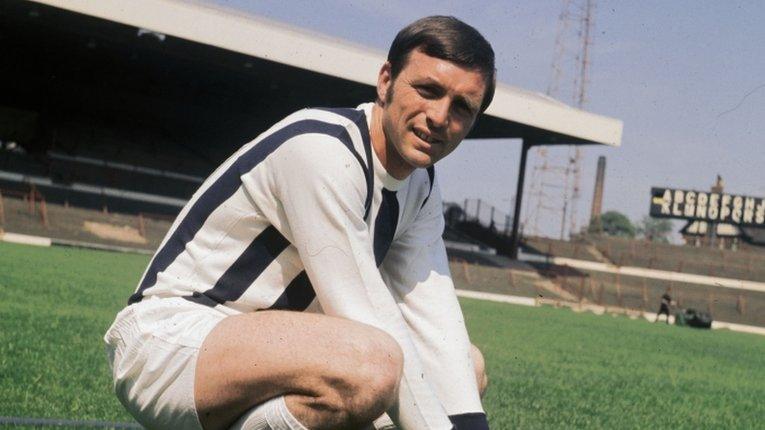

Rose Reilly jumps for the ball during a game in France in 1974

Commonwealth Games bronze medal-winning judo star Connie Ramsay and former rugby international Lee Cockburn have also pledged to donate their brains to the Glasgow Brain Injury Research Group, external, run by internationally renowned researcher Dr Willie Stewart.

He recently published a landmark study showing that former professional footballers were 3.5 times more likely to die with neurodegenerative disease than other people.

His research concentrated on male athletes. There is far less study of the effect on female brains of trauma to the head.

Dr Stewart said: "Despite the many advances in understanding outcomes from brain injury we and others have reported, we must recognise that sex differences have not been adequately explored."

It is believed women experience higher rates of concussion than men when comparing like-for-like sports and there is also evidence that girls may take longer than boys to recover.

Katherine Snedaker wants to raise awareness of the risks to women

The Glasgow Brain Injury Research Group has announced a partnership with US-based charity Pink Concussions in a bid to bring attention to female brain injury research.

Katherine Snedaker, from Pink Concussions,, external told BBC Scotland's The Nine: "Overall there is more male brain injury than female because men take more risks - or, informally, do more stupid things."

She said male brain injury had been studied more but there was evidence that women were twice as likely to suffer concussion in similar situations.

Ms Snedaker said some work had shown that biological differences such as neck strength and head circumference could make a difference.

"There was a paper out last year that shows that the nanotubular axons in women's brains are narrower and less complex than men and have a vulnerability," she said.

Connie Ramsay (right) with Stephanie Inglis at the Glasgow 2014 Commonwealth Games

These structural differences place women at greater risk during trauma.

There is also a belief that hormonal or menstrual changes can make a difference.

Ms Snedaker said this did not mean women should be held back in sport or other areas where they wanted to advance but they needed to be aware of the risks and get immediate care.

She said her Pink Brain Pledge hoped to get women in the UK to donate their brains after death.

As well as sports concussion, she is interested in how other traumatic incidents can affect women's brains such as domestic violence, accidents or military service.

Ms Snedaker said: "I pledged my brain in 2011 and I felt like I joined the team.

"When I found out I had cancer in 2013 I called the lab and said 'Are you still gonna take my brain?' and they said 'We think you're a little crazy that's important to you'. But it was important to me."

Access to post-mortem human brain tissue has been crucial in helping researchers recognise the link between a brain injury and degenerative brain disease.

Ms Snedaker said: "It's really hard to study the brain when someone's alive so post-mortem tissues are essential and we do not have enough female brains."

- Published15 January 2018

- Attribution

- Published21 October 2019

- Attribution

- Published6 June 2019