General Election 2019: Do firms have purpose beyond profit?

- Published

Nationalised companies are on the way back, in Scotland and in the rail sector.

One of the reasons is that the British model of the firm is so tarnished and unresponsive to the needs of the age.

Radical reform is being urged that would force firms to consider responsibilities beyond their shareholders.

The election campaign has brought back a big debate about the reach of the state into the economy and ownership of companies.

Labour wants to nationalise rail, mail, energy supply, English water companies and broadband. It wants the state to become a manufacturer of medicines.

Rivals see this as a retro reach into the seventies, when public ownership got a bad name.

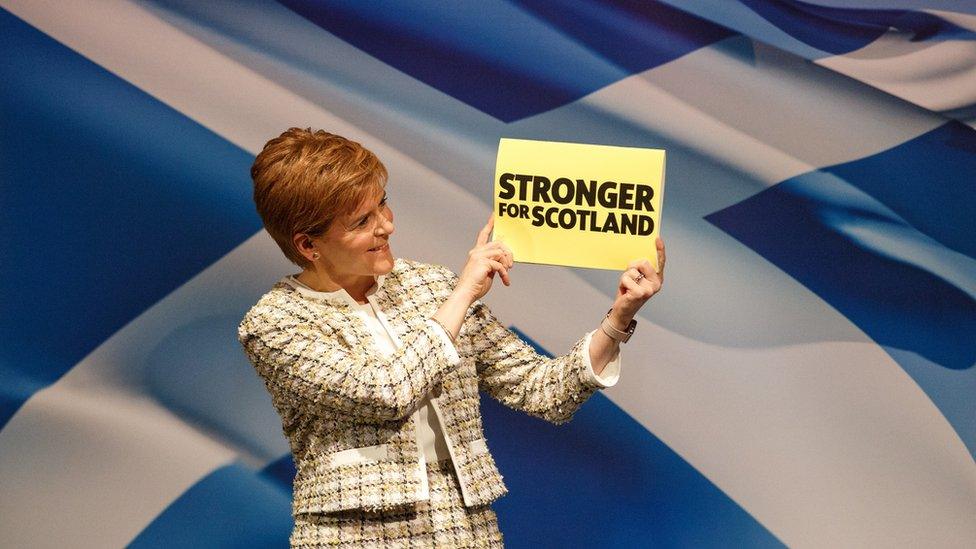

The SNP hasn't had much to say about that part of Labour's plan.

The Scottish government started a long road towards nationalising the Ferguson Marine shipyard in Inverclyde (still not completed),

I have looked at the case for public ownership more widely and it's a particularly lively debate in the rail industry, where even Tory ministers were on the verge of ripping up the franchise system, had Brexit and this election not got in the way.

LNER operates services on the East Coast Main Line and is currently being run by the UK government after a string of private franchise operators could not make a go of the route

British franchise tenders are usually won by train operators owned by foreign governments, now including Germany, France, the Netherlands, Italy, Belgium and Hong Kong.

And with the repeated failure of private firms to keep the East Coast main line on financial tracks, the UK government is back as an operator.

A third way

But there's another side to this debate, which questions the future of the private sector and whether the Great British company is fit for purpose.

One of country's leading business thinkers, professor Colin Mayer of Oxford University, said this week that we have a particularly toxic form of capitalism in the UK - and it needs radical change.

Where these two arguments meet in the middle has the potential to create a dynamic for a very different type of economy.

Instead of, or in addition to, nationalising companies, there is the potential to change the way companies operate, directing them at a wider range of outcomes than profit.

Remember the Third Way , external- the Tony Blair and Bill Clinton project in the late 1990s to find a new type of mixed economy? It never alighted on a compelling answer. But perhaps there's the start of one in such a radical rethink of the company.

Leave us kids alone

What has changed to make that possible? Trust in business has been in short supply since the financial crash. It's recovered a bit, according to the Edelman trust tracker, and is now stronger than trust in government or the media.

There remains pressure over pay inequality within firms, and for the top 1%. As shareholders, they are taking the benefits of both globalisation and of a skewing of the benefits of corporate growth, while less goes to workers.

The financial district of London contributes billions of pounds to the UK economy every year but the way the firms located in the 'Square Mile' operate is coming under greater scrutiny

Big technology corporations are causing concern over their immense power over personal data.

There is pressure over climate change, with corporate responsibility for that being highlighted by protesters globally.

And there's a younger generation, which seems to adhere to different values, preferring to work for companies with values they support - not just to make money. In a tight labour market, millennials are better placed to name their price, and it's not just financial.

In summer, a round table of the top 100 American chief executives signed a letter saying the business model for the firm needs change, to remove the primacy of shareholder interest. It should, instead align the firm with the interests of customers, workers, wider society the the environment.

The shifting capitalist plates

One of those who signed the letter was a Scot, Kevin Sneader, the most senior partner for McKinsey management consultancy. I interviewed him soon after, and he argued that we'd reached the end of a belief that '"the business of business is business".

There's a belief that business is the provider of the prosperity that can solve social problems and put food on the table, but it has to play a part in the communities within which it operates.

If it doesn't provide ways through the challenge of automation for its own workers, he says business will reap the consequences. In many countries, notably the USA, if it can't find solutions to the challenge of ever-rising healthcare costs, it will suffer from the payroll costs of insurance.

Labour wants to take the National Grid, and the retail arms of the big energy firms, into public ownership in a move which has sparked some of those affected to move their registered offices overseas

Into the debate comes the British Academy, with a project led by Professor Mayer.

Last year, it pointed out that corporate Britain doesn't have to be this way. It is only in the past 60 years that it has become focused on profit maximisation. Down the centuries, corporations developed as "purveyors of education, civic administration, public works, philanthropy and spiritual enlightenment".

Mayer now wants to make it the norm rather than the exception for a firm to have a purpose other than maximising shareholder returns. Firms can vary their purpose, under the Companies Act, but tend not to do so.

Social enterprises have been growing in number and reach, but mainstream firms stick to shareholders as top priority.

In turn, shareholders tend not to see responsibility or obligation to a firm long-term, or to society.

And Prof Mayer points out that British law is more relaxed than even American ones in allowing investors to pressure firms into short term gains at long term costs to workers, customers, society and the environment.

Go outdoors

Many companies can point to social engagement by their staff, at least as an add-on rather than a core purpose. But it could be so much deeper.

In the US, where Black Friday became a thing to tap into consumer time to browse and splurge the day after Thanksgiving, one company has gone in the opposite direction.

REI, a big chain selling outdoor sport and adventure gear, closed stores on Black Friday, and told its staff and customers to go out and enjoy the outdoors for the day. That included a series of environmental clean-up projects.

The cynical might see that as itself a marketing ploy. But it demonstrates how longer term profit can be linked to alternative corporate goals, as well as engagement with consumers and a little generosity to staff.

CONFUSED? Our simple election guide, external

POLICY GUIDE: Who should I vote for?, external

REGISTER: What you need to do to vote

- Published27 November 2019