'Huntington's has affected everyone I ever loved'

- Published

Sandy Patience, who is married to Laura, says many people, not just him, are hoping to benefit from the clinical trial

Sandy Patience's mother died of Huntington's, his sister is in a care home because of it and now he knows that he has also got the degenerative condition.

Sandy, who was diagnosed three years ago, says the disease has had a massive effect on his family.

"Everyone I have ever loved has been affected by this illness," he says.

The 57-year-old is one of the first people in Scotland to take part in a clinical trial which aims to find out if a new gene-blocking compound can slow the progression of the disease.

Sandy, originally from Avoch on the Black Isle and now living in Inverness, is among only nine people in Scotland and 801 globally to be taking part in the Generation-HD1 study, being led in Aberdeen by Professor Zosia Miedzybrodzka.

Huntington's disease - often known as HD - is a rare inherited condition that damages nerve cells and stops parts of the brain working properly over time.

Huntington's disease

Sandy undergoes tests as part of the trial

About 8,500 people in the UK have Huntington's disease and a further 25,000 will develop it when they are older

Huntington's generally affects people in their prime - in their 30s and 40s - and patients die about 10 to 20 years after symptoms start

Some patients describe it as having Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and motor neurone disease rolled into one

There is currently no effective treatment to halt or slow its progression.

HD is caused by a faulty gene. Each child of a parent with Huntington's has a 50% chance of developing the condition.

'It eats people up'

Sandy's mother died almost 40 years ago at the age of 59

Sandy says his mum was 59 when she died but had been ill for a long time.

"I had a very difficult childhood - instead of going to play football, my life was going to the hospital to visit relatives struck down by this horrible illness," he says.

The disease has cast a shadow over his life, he says, with his grandmother and aunts also being affected.

His older sister Helen was diagnosed about 30 years ago but over the past decade she has deteriorated severely and is now in a care home.

"Huntington's has robbed her of everything apart from her wonderful wit and a determination to keep going," he says.

"I look at her in the bed and it's just like when mum was there."

Sandy says Huntington's "eats people up".

"Seeing family members suffer and understanding that might also be your future is a very difficult thing to deal with."

In 2017, Sandy decided to undergo a genetic test to see if he had the condition and was "absolutely devastated" to find out he had tested positive.

Sandy told his wife Laura to leave him when he got his diagnosis

"I even asked my dear wife Laura to find someone else because of my understanding of my diagnosis, because I loved her so much. Her response was the same back 'but I love you too much to leave you'," Sandy says.

A few weeks later he was watching BBC news when he found out about the first phase trial for the study.

He says he emailed everyone on the TV report to get a place on the trial.

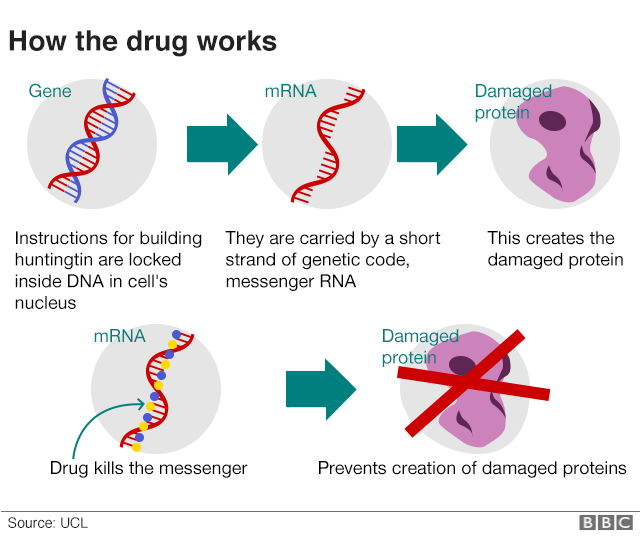

The trial drug is a short strand of genetic code that will bind to the mutant Huntington gene product.

It is hoped this process will slow the progression of HD and lead to a much-improved quality of life.

Aberdeen is one of 11 sites across the UK participating in the worldwide trial which takes in 15 different countries.

Sandy travels every two months from his home in Inverness to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary where a sample of his brain fluid is taken for analysis, after which, a trial drug (RG6042) or a placebo is administered.

He does not know whether he is on the trial drug or the placebo but he says taking part in the trial has had a positive effect on his life.

"It feels like I'm doing something positive for the first time to fight this horrible illness and make a difference to people's lives in the future," he says.

Sandy's daughter is negative for the Huntington's gene so his grandchildren will not be affected

Sandy says his daughter Kimberley tested negative for the gene, meaning she and her children will not be affected.

"I can't put into words what that means," he says.

The first phase of the drug trial appeared to show it was safe and reduced levels of the toxic protein that builds up in patients' brain cells and is believed to trigger the disease.

However scientists still have to show that RG6042 actually delays or halts the progression of the disease once it has taken hold of patients' brain cells.

Prof Miedzybrodzka said: "Obviously, there is a long way to go yet, but the trial does at least offer real hope to Huntington's families.

"Those volunteers who meet the criteria to take part are playing an important role for the entire Huntington's disease community."

- Published11 December 2017

- Published18 November 2019

- Published23 January 2018