New law to protect children giving evidence in court

- Published

In many cases, children will not have to attend court

Child witnesses in the most serious crimes are no longer to be asked to give evidence in court.

Instead they will be questioned in dedicated witness suites and their testimony will be pre-recorded to be played later to a jury.

The Vulnerable Witnesses Act which came into force on Monday, draws on the Scandanavian system of Barnahus - or children's house.

Charities said the new system will help ensure witnesses are not retraumatised.

The change, which will apply to cases in the High Court, will spare under 18s from giving evidence during a trial.

It will allow child witnesses in cases heard before a jury to record their evidence in advance of a trial for crimes including murder, sexual offences, human trafficking and domestic abuse.

As a result they will not have to face the accused in court.

Justice secretary Humza Yousaf hailed the significance of the new legislation

Justice secretary Humza Yousaf said the act marked a significant milestone in Scotland's journey to protect children as they interact with the justice system.

He said: "Children who have witnessed the most traumatic crimes must be able to start on the path to recovery at the earliest possible stage and these changes will allow that, improving the experiences of the most vulnerable child witnesses, as far fewer will have to give evidence in front of a jury.

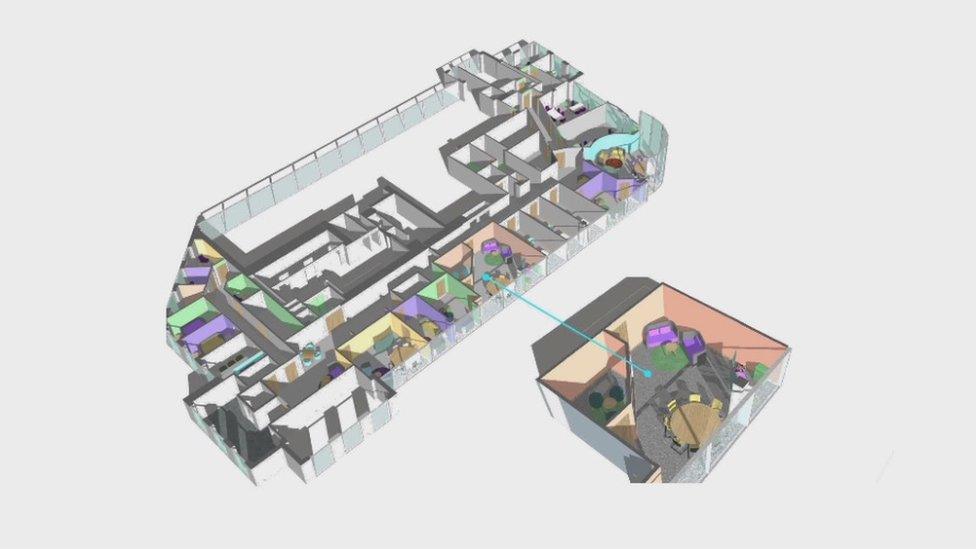

"Legislation is only one part of the jigsaw, backed by the development of modern, progressive and technologically advanced facilities to ensure children are supported to give their best evidence."

The new system draws on the Scandinavian experience of reducing the amount of interviews a child has to go through if they are a witness or victim.

Ideally this would be a single forensic interview, taken in as child-friendly a setting as possible.

This includes not only the décor and surroundings, but also providing support from different agencies on-site to help a child deal with any linked traumas or health issues that also need attention.

The one-to-one interviews are recorded and can be watched remotely

What is the Barnahus system?

The literal translation of Barnahus means "Children's House".

It was first developed in the United States before being adopted in Iceland in the late 1990s.

It later became the model for other Scandinavian countries - Sweden, Norway, Greenland, Denmark and a pilot in Finland.

It places a wide range of support services for child abuse cases under one roof, putting the care and welfare of the child at the centre of all decision making.

In particular it recognises the harm and trauma that multiple interviews in different locations and with a number of different agencies can have on a child and their families.

Forensic interviews, medical examinations and access to therapeutic services can all take place in one place.

The charity Barnardo's said in Iceland, its introduction had a significant influence on the number of children finding the confidence to come forward to seek help and make disclosures.

It had also led to a notable increase in conviction rates.

The legislative changes were proposed by the Scottish government in late 2018.

But Holyrood's justice committee called on ministers to go further, external and fully adopt the Scandinavian Barnahus principles into Scots law, adapting them to the Scottish context.

MSPs had visited the Barnahus in Oslo to gather evidence on how it worked.

A new suite, modelled on the Scandinavian system has already opened in Glasgow and aims to provide a less daunting setting than a court for vulnerable witnesses and complainers to give evidence in.

Similar facilities are planned in Edinburgh, Inverness and Aberdeen.

The aim of this Barnahus in Norway is to make the environment secure and welcoming

A diagram of the witness centre in Glasgow

Justice committee convener Margaret Mitchell said: "We recognise the potential stress caused by giving evidence, and we want to ensure steps are taken to avoid children being re-traumatised by the court processes.

"On our visit to Oslo, we were struck by how the Barnahus provided wrap-around support. Members therefore welcome the Scottish government's ongoing work to introduce a similar approach for child victims and witnesses in Scotland."

Mary Glasgow, chief executive of the charity Children 1st, said: "Children have told us that they found giving evidence in court almost as traumatic as the abuse itself.

"This act means more children will now be able to give pre-recorded evidence in an environment more suitable to their needs.

"It also reduces the time children wait to give evidence and means they will not have to face the accused."

Ms Glasgow added that pre-recording would enable experts to bring all the different services a child might need together under one roof.

- Published24 January 2019

- Published13 June 2018

- Published2 May 2018

- Published1 May 2018