Genetic scorecard finds under-threat Scots species

- Published

Heather is one of the species that makes up Scottish national identity

Scottish scientists have developed what they say is a "world-first" method of understanding and conserving wildlife.

The red squirrel, golden eagle, harebells and heather are among the species which make up a big part of our national identity.

Now a report coordinated by Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) has detailed a new method to measure the genetic diversity of our wild things.

It is not a spiffy new piece of laboratory kit. Instead it's a "scorecard" that assesses the genetic diversity of, and risks being faced by, target species.

The red squirrel is a Scottish species that needs to maintain its biodiversity

Genetic diversity is a measure of how genetically varied individuals are within a species.

Biodiversity matters because it makes living things more resilient. Organisms that are too similar genetically could leave a whole population at risk from an outbreak of a single disease.

David O'Brien, SNH's biodiversity evidence and reporting manager, says the study is part of Scotland's response to the UN's Aichi programme to promote biodiversity.

"Aichi is very much focused on species of socioeconomic importance, areas like agriculture, horticulture and forestry," he says. "We thought, what about wild species?"

As well as wildlife, plants such as the harebell are on the list

So the team selected 26 wild species, most of which had been nominated in an earlier poll of Scots as important parts of our national identity.

Each has conservation or cultural value or is important for food and medicine.

It is not just wild creatures. Plant-life like the harebell (or Scottish bluebell, to give it its Sunday name) and Scots pine are on the list too.

Also studied was one organism that is both widespread and almost unnoticed: papillose bog-moss. It's common wherever it is damp.

Given that our nation can sometimes seem like one giant rain-soaked sponge, that's a lot of moss.

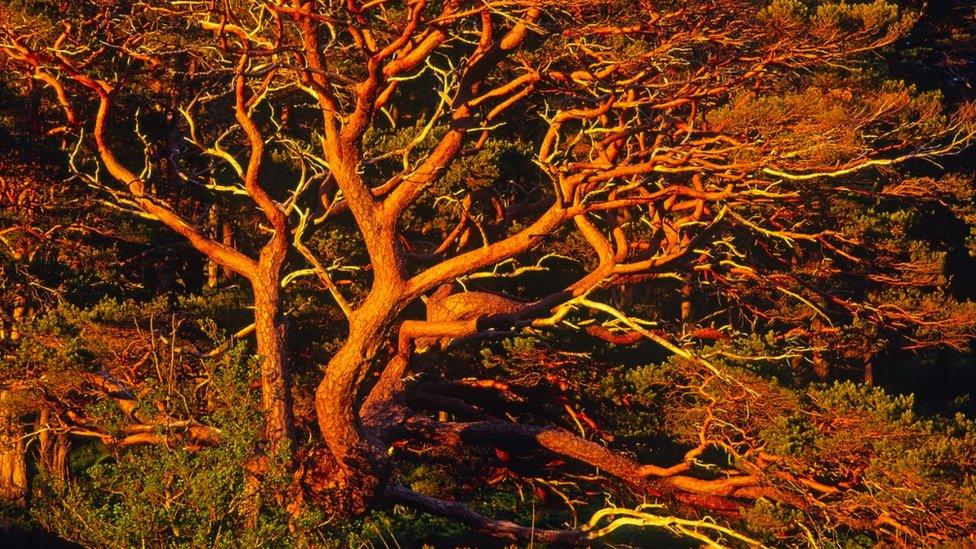

Scots pine is also on the list

Mr O'Brien says it has an environmental and economic importance we might not fully grasp.

He says: "It removes carbon from the atmosphere. It cleans our water. And it creates peat. Without peat, no whisky."

The researchers found four of the species they assessed - wildcat, ash, the great yellow bumblebee and freshwater pearl mussel - were at risk of severe genetic problems.

The threats include non-native species, disease, habitat loss and pollution.

Ash trees are at risk of chronic fungal disease ash dieback

Among the possible challenges faced by ash trees is the chronic fungal disease ash dieback.

But the genetic scorecard means Mr O'Brien is more optimistic about the species' survival in Scotland.

He says: "Most ash in Scotland is wild and not in plantations. So it's genetically diverse and is likely to be more resistant."

Work is already under way to protect other genetically threatened species.

In 2018, BBC Scotland reported that researchers at the Royal Scottish Zoological Society had pronounced the Scottish wildcat "functionally extinct" in the wild because of interbreeding with domestic cats.

Scottish wildcats are "functionally extinct" and wild genes could be reintroduced from captive animals

Now the Saving Wildcats project is aiming to reintroduce wild genes from captive wildcats and if necessary from continental Europe.

SNH's Biodiversity Challenge Fund recently announced a cash boost for work to improve key populations of freshwater pearl mussels.

And the Beinn Eighe nature reserve in Wester Ross has become the UK's first genetic conservation area to protect the diversity of the Scots pine.

The new genetic scorecard will lead to more long-term conservation strategies and help hit the international Aichi targets.

It establishes a method that can be adapted to any country on the planet.

The Great yellow bumblebee is another species under threat

It is the result of collaboration involving more than 40 experts from 18 universities, research institutes and conservation bodies, among them Edinburgh's Royal Botanic Garden.

Prof Pete Hollingsworth, director of science at the Botanic Garden, describes genetic diversity as "the raw material that allows species to evolve and adapt".

"Conserving genetic diversity is key to species adapting to changing climates, to new diseases or other pressures they may face," he says.

Freshwater pearl mussels are at risk from a lack of genetic diversity

Co-author Dr Rob Ogden, head of conservation genetics at the University of Edinburgh, says the scorecard "allows every country to assess its wildlife genetic diversity".

"What we measure in Scotland can now be compared around the world," he says.

The work was supported by the SEFARI Gateway, the knowledge exchange hub for Scotland's environment, food and agriculture research institutes.

The Scottish government's environment secretary Roseanna Cunningham says the report "provides us with new and powerful insight into the state of the genetic diversity among wild species".

- Published20 December 2018