Coronavirus: Scottish music industry hit by Covid-19 'catastrophe'

- Published

- comments

The future of many venues could be in doubt if there is a prolonged period of social distancing

Coronavirus has been "catastrophic" for Scotland's music industry with more government support essential, the head of a trade body has warned.

Robert Kilpatrick, from the Scottish Music Industry Association (SMIA), said support was needed to prevent irreversible damage to the industry.

A prolonged period of social distancing would jeopardise the future of many venues, he told BBC Scotland.

Mr Kilpatrick's concerns are echoed across the country and the industry.

"The business model just doesn't work when it's not based on quantity," said Mr Kilpatrick, whose organisation represents 3,000 members from artists to studios to record labels.

A failure by the Treasury to extend financial support until a time when venues can be reopened safely and profitably could "result in a period of inactivity that we wouldn't be able to recover from," he added.

At Castlesound Studios in the East Lothian village of Pencaitland, Stuart Hamilton has spent 32 years building a reputation as one of the finest recording engineers in the land - but even he is now facing potential ruin.

"I think I have two or three months that I can sustain things," he says. "After that there really is going to have to be some income for the studio to continue."

Robert Kilpatrick is worried the industry would not be able to recover from a prolonged period of inactivity

If there isn't, he worries about how he will pay for his mortgage and support his family.

Safe individual recordings in isolated sound booths would not keep him afloat, he says, even if there were any demand for them, which there is not.

"Music is made by human beings interacting with each other and very often that interaction does require them literally to be sitting, watching each other's fingers," he explains.

Sometimes, says Mr Hamilton, "we'll have 20 musicians all sitting beside each other and there is no other way of recording that kind of music.

"If it's a jazz big band or a string section, you can't record these things one person at a time."

The award winning singer-songwriter Karine Polwart has recorded often at Castlesound and she too frets about the future of the entire music industry.

"You have recording studios, you have videographers, you have venues, promoters, festivals, managers, agents," she says.

"There's an incredible network of people involved in making the whole thing tick and we as musicians ourselves are just the front-facing aspects of that. We need all these other people behind to make the whole thing work."

Karine Polwart says she's concerned about the future of the entire industry

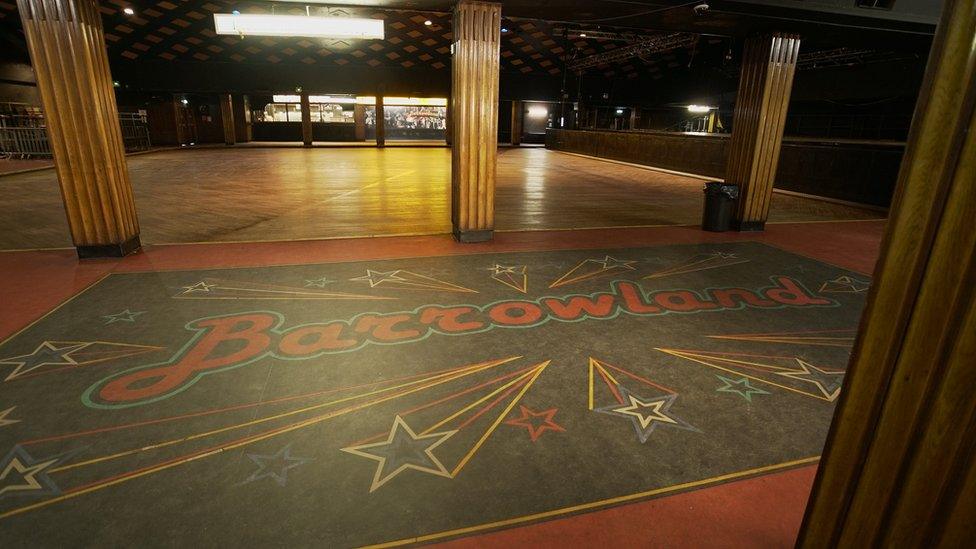

One of those people is John Swift, who manages the bars at the Barrowland Ballroom in Glasgow, one of Scotland's oldest and best-loved concert halls.

Plans for a centenary celebration of the venue next year are now on hold as the nation prepares for a long stretch of keeping at least two metres apart in public.

This weekend should have seen Yungblud and The Orb performing here but their gigs have been postponed, the ballroom is silent and there seems no prospect of it coming back to life while social distancing rules are in force.

"We don't know how we're going to get around that. Nobody does," says Mr Swift.

Going to a gig is a shared, intimate experience. The atmosphere at the Barras with its low ceiling and sprung dance floor isn't incidental, it's essential — "the heartbeat of the place," as Mr Swift puts it.

"It's what makes the Barras, the Barras. The place just comes to life," he says.

The owner of the Glad Cafe in Glasgow says gigs with smaller audiences just don't make financial sense

The lack of concerts means an uncertain future not only for the 20 or so bar staff, but for the cloakroom attendants and the caterers, the cleaners and the bouncers, the engineers and the crew. The list goes on.

Smaller venues and their staff are reeling too.

On Glasgow's south side the Glad Cafe shut its doors on 17 March as the pandemic swept into Scotland.

Putting on gigs with many fewer customers "would just ruin the business", says founder Rachel Smillie. "We could not survive. We know that."

Ensuring people stay apart at concerts is further complicated by the fact that the music industry's profitability is bound up with booze, especially in the streaming era when the main source of revenue has shifted from recordings to live shows.

Takings from the bar are crucial but alcohol and social distancing do not mix well.

Venues and musicians should be earning the bulk of their income for the year right now

Now would be a good time for consumers of recorded music to reconsider their reluctance to pay for it, says Mr Kilpatrick of the SMIA.

In addition to the social and cultural value which listeners place on music, he says, there should be "a fair economic value that's placed on it as well because without that it can't be sustained".

For now, both Ms Smillie and Mr Hamilton say they are grateful for government grants to tide them over and furlough schemes to help staff - but both agree the money amounts to emergency surgery rather than a cure.

Like many business owners they are reluctant to take on big loans without an idea of when, how or even if they will be able to pay them back.

Even if restrictions are eased and government support is scaled back, many are worried about the timing. If that were to happen later in the year, traditionally a fallow period for music production and performance, it could be disastrous.

Where are people looking for comfort and solace? They're looking to music and film and television and books

The industry is cyclical, explains Karine Polwart. If you haven't made enough money on the long summer evenings you may well struggle financially through the dark winter nights.

This is the start of the earning season, she says, "when most venues, musicians, promoters, managers make the bulk of their annual income".

But Ms Polwart is keen to stress that this is not only a financial crisis.

The cultural impact of a hiatus in the production of music is "massive," she argues, especially in this time of stress.

"Where are people looking for comfort and solace? They're looking to music and film and television and books," she argues.

"Literally millions of us are being sustained by those products of creative activity," says Ms Polwart, echoing the warning of the SMIA that creativity is being stifled and emerging talent crushed.

The folk and pop artist says she has watched with alarm as musicians "in real need and panic" scramble to produce output on the internet "of very, very varied quality".

Rachel Smillie: Scotland's music industry needs a "heck of a lot of support"

She worries that artists are being conditioned to be grateful for tips online rather than to expect payment for their performances.

And she is deeply concerned about the implications of a prolonged period of physical distancing although, like all those we interviewed for this article, she accepts that it may well be necessary to protect public health.

Ms Polwart cautions that there is a "real danger" of long-term damage to the music industry.

Ms Smillie agrees.

"We just can't imagine a future without small venues such as ourselves having an important part in their local neighbourhood," she says.

"If that's to continue in Scotland then we are going to need a heck of a lot of support."