Coronavirus in Scotland: The patients' stories

- Published

Six weeks ago we reported from the intensive care unit (ICU) at University Hospital Monklands in Airdrie, North Lanarkshire, where we met three patients being treated for Covid-19.

What happened to them after we left the hospital?

John Johnstone

John Johnstone said going into intensive care was a frightening experience

"I only thought I had a cold," says John Johnstone, who is now back home in Coatbridge after spending more than a month in hospital including a week in intensive care, an experience he calls "daunting."

"You're getting wheeled into the room and all you're seeing is machines with wires, tubes. It takes you aback," he says.

"It was really frightening...you're going into the unknown."

Mr Johnstone, 57, was shielding when the outbreak began because of a previous kidney transplant and has no idea how he picked up the coronavirus.

When we met him in the ICU on 1 May, he was conscious but on a ventilator and unable to communicate except by writing a few words on a small whiteboard.

It was "really uncomfortable," he says, "you can't communicate with anybody...really, really frustrating."

You wiped away a tear when we spoke to you, I remind him.

"Aye, the emotions setting in. I think I've got a lot of emotions running at the time," he says.

'It has taken a lot of good people'

Mr Johnstone is a Rangers fan and coach driver with, he says, a reputation for being grumpy. He apologises when he becomes emotional as he recalls his experience, as if he is still surprised by his own reaction to the trauma and stress he has endured.

"It has taken a lot of good people, this disease," he says.

While he was in the hospital, he learned that his best friend Donald Bagley had died with Covid-19 at the age of just 62.

"My wife and my mates actually tried it keep it from me — that he had died of it," he explains. "Eventually they had to tell me. I broke down. I'm in a room myself and I broke down.

"He was the very first one to phone me when I went into hospital. He says: 'Wee man, you can fight this. I know you can fight it.' He was the very first one and those were the last words I heard from him.

"I was determined to fight it, for myself, for the family, also [for] Donald as well."

John with his wife and granddaughter Daisy

Now back home with his wife, daughter and Daisy, the youngest of his grandchildren, Mr Johnstone is, he says, "getting stronger everyday."

In the hospital, when I asked him to sum up his message to the doctors and nurses caring for him, he shook his head.

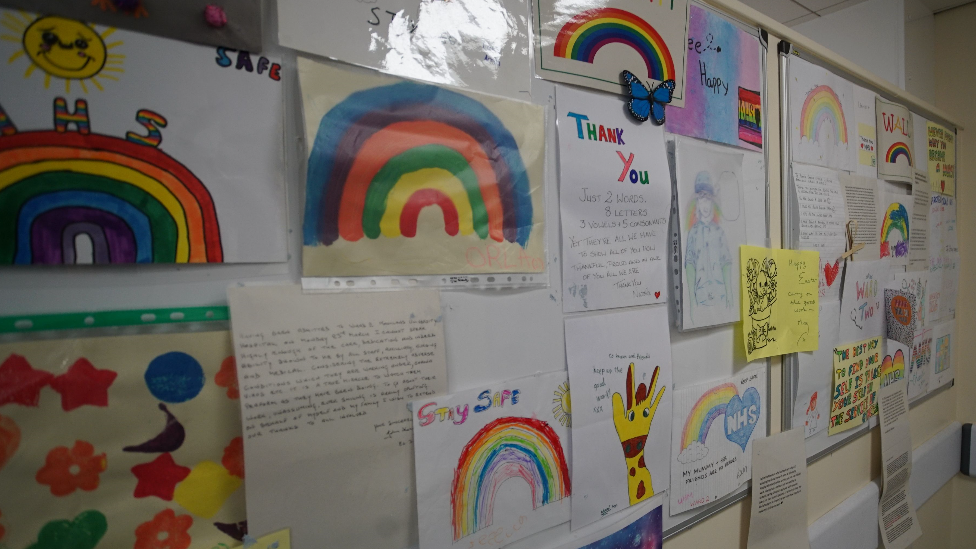

"There are too many words to say to them," he managed to write before stopping to wipe away a tear.

He still feels that he does not have the words to do justice to the NHS staff, he says.

"They're absolutely amazing at what they do. Every single one of them. And they're actually putting their own lives on the line.

"They don't want to class themselves as heroes, but they are.

"They're outstanding. Every single one of them. Every single one."

John Houston

Mr Houston's family wanted this picture of him in intensive care to be seen as a warning about the dangers of coronavirus

John Houston had left intensive care four days before we arrived in Monklands, but while we were there he was brought back in on a wheeled bed.

His kidneys were struggling to cope with Covid-19 and he needed filtration treatment.

A nurse helped to connect him to clear plastic tubes and brightly-coloured cables before adjusting the bed to make him more comfortable.

Mr Houston told us he had been admitted to hospital three weeks earlier and that he was missing his border collie, Cody.

The nurse suggested a video call with the dog, but Mr Houston was worried that Cody would be too excited.

While he was lucid as we were speaking to him, Mr Houston told us that during his previous spell in ICU he had been given medication which made him hallucinate, a common experience for seriously ill patients which he described as "a bit scary".

Mr Houston looked ashen and frail but as we left he gave us a wave, a thumbs up, and a smile.

Eight days later he died of organ failure, aged 60.

His family told the BBC they wanted people to see the pictures of him in intensive care as a warning about the dangers of the coronavirus.

John Houston with his beloved border collie, Cody, before he became ill

They said he had cried when he learned that he had the virus because he was worried about passing it on to the nurses who were treating him.

At home in Airdrie, where he was known as JT, Mr Houston was well-known and well-liked.

He used to deliver prescriptions in the town and in nearby Coatbridge before he studied for a degree in sociology and volunteered with the Scouts, who formed a guard of honour at his funeral.

His dog, Cody, was allowed in to the hospital to see him for one last time.

Irene Norwood

Irene Norwood says she still has "good days and bad days"

Irene Norwood is back home in Cumbernauld, but says her recovery remains a struggle with many ups and downs.

"I have good days," she explains, "and I have days where your mood is so low — and that's not my personality. I've always been a really happy and upbeat person and this is so new to me."

She has been experiencing flashbacks and believes she may be suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Returning to her home, which she shares with her husband and three sons, has been a lot harder than she thought it would be, says Ms Norwood who is a 51-year-old housewife.

"Learning to walk again was so scary because you don't think for one minute you'll forget remembering to put one foot in front of the other."

"[I thought] I'd be making the dinner, doing my housework. Life would be fantastic," she says. "It's not the case."

Ms Norwood has several underlying health conditions including chronic kidney disease and had been living with one kidney before the virus put her into hospital for two months, including two spells in intensive care.

"When they took me back up to ICU for the second time I was devastated because I just had good news that day that my kidney was starting to function and I was so happy," she says. "I was absolutely elated and when they said about going back to ICU I felt devastated, absolutely devastated."

Ms Norwood had to learn to walk again and says her recovery is still a struggle

She says she now gets tired very quickly, she is relying on a walking stick a lot, has had "quite a few falls" and is experiencing a recurring tremor down her left side.

"So cooking with hot products can't happen. I can't trust myself to be lifting pots because I don't know when it's going to come on," she says. "I fell through the night a few times getting up to the toilet."

Covid-19 is, she insists, a psychological condition as much as a physical one.

"I don't think they understand just how bad the mental side of things are," she says.

"You have days that you feel you can't go on. But every day you have to turn up because to say that I'm upset or I am sad or I'm miserable, that's really selfish because I'm alive. I've made it through Covid and so many people haven't.

"And that, I think, is something you really have to always remember when you're at your darkest moment. You made it.

"And it's through the care and attention that you got in hospital, because I honestly believe that's why I'm still here. The staff were absolutely astounding. I cannot thank them enough."

EXERCISE: What are the guidelines on getting out?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

AIR TRAVELLERS: The new quarantine rules

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?