'I regret atom bombs but they are why I'm alive'

- Published

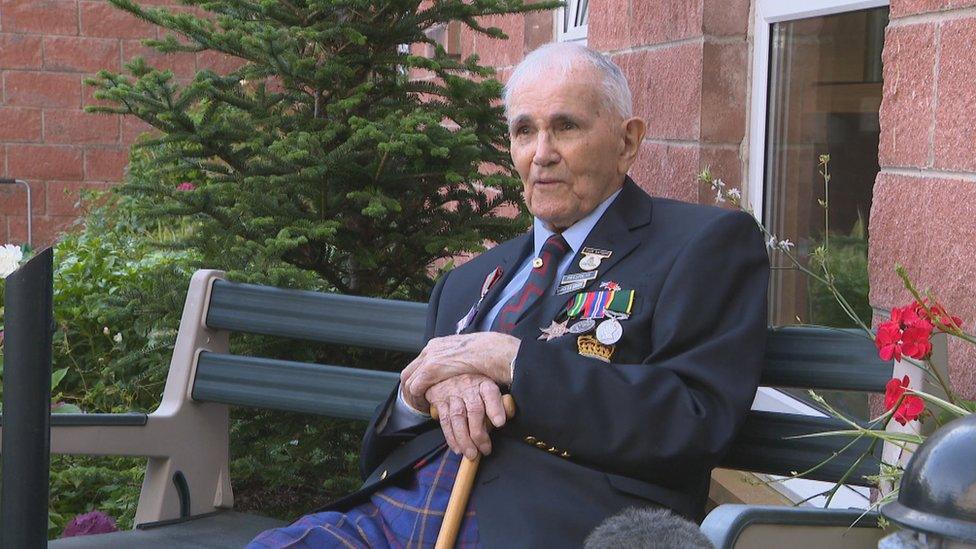

Jack Ransom regrets that atoms bombs were dropped to end World War Two but says without them he would not have survived to be 100.

His uncle, whose name he shares, had died during World War One at the age of 19 and Jack says he could easily have not survived the brutal treatment at the hands of the Japanese if World War Two had not been brought to a final conclusion on 15 August 1945.

Jack was standing at the gates of Changi jail in Singapore when he discovered his ordeal was over.

He had been a prisoner of the Japanese for more than three years, during which time he had been forced to build the infamous Burma railway and carry out other punishing work on rations of just a bowl of rice a day.

When he was liberated he knew nothing of VE Day four months earlier, which marked the end of the war in Europe.

He was also unaware that Japan had finally surrendered after atom bombs were dropped on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

All the 25-year-old artilleryman knew was that the Japanese guards who took him every day to work on digging defence tunnels had failed to turn up.

"The first sign that I had was a paratrooper walking up the road towards the jail," he said. It was from him that Jack learned the war was finally over.

Dressed in rags

Jack weighed just six stones and describes himself as looking like a scarecrow, dressed in rags and no shoes.

Seventy-five years on, he says he was "bloody lucky" to survive his horrendous punishment as a prisoner of war.

The veteran, who is originally from Peckham in London but has lived in Largs for many years, had joined 118 Field Regiment Royal Artillery at the start of the war but did not leave Britain until November 1941.

He left from Liverpool for Halifax, Nova Scotia, where he transferred to an American troop ship and sailed to South America and across to South Africa.

America was not officially in the war when they set off but while the convoy was in Cape Town the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour, bringing the US into the conflict.

Jack went to India before sailing to Singapore in January 1942.

"Our job was to use the guns to fire on the Japanese who at the time were across the straits in the Malaya peninsula.

"It was jungle on the other side so whether you hit anything or not you don't know."

British soldiers were told to surrender in Singapore

On 15 February 1942, Jack was told to surrender because of the heavy punishment the main town on the island was taking.

The troops were ordered to destroy as much as they could before the Japanese arrived and took them prisoner.

Jack was taken to Changi prison camp in Singapore but at the beginning of 1943 he was sent to work on the Burma railway, often called the Death Railway.

About 12,000 Allied prisoners died during the construction of the railway that ran 250 miles between Thailand and Burma (now Myanmar), to supply troops and weapons in Japan's Burma campaign.

Jack says he was one of the final groups to be sent to the railway and thousands had already died from cholera and other diseases.

He was forced to march about 200 miles from the start of the railway to where they were to work building an embankment.

"We lost people along the way," he says. "They fell by the wayside and died. They just left them."

"It was a hard job," Jack says. "The embankments were 6ft or 8ft high. We had to scoop earth up and build them up. We had no machinery it was just four men and two shovels."

British Troops tried in vain to stop the Japanese at Singapore

The Japanese were brutal, he says, and the prisoners worked from dawn to dusk with hardly any rations.

"We lived on a mess tin of rice per day," he says. "That's all we got."

After the railway was finished at the end of 1943 he was taken back to Changi jail in Singapore where he did more hard labour digging defence tunnels or levelling land for the airport.

Then one morning in August 1945 it ended.

Jack says the gates to the jail were open but nobody knew what to do.

"After three years of being a prisoner of war you weren't going to stick your nose out of the door and get your head shot off," he says.

It was the paratrooper who confirmed the news that they had dropped the atom bombs and the war was over.

A month later he got his transport home. Jack says he started the journey on the Polish boat at six stone and arrived home 12 stone.

"They gave us bacon eggs and bread and butter," he says. "I dreamed of a slice of bread and butter."

The events of 75 years are still fresh in Jack's memory.

"I always think every day of my comrades, my pals, who didn't come home but I also think of the civilians in Japan who suffered the two terrible atom bombs. I have a sense of regret that happened.

"But you have got to be honest. I would not be alive if it wasn't for the atom bombs."