Is Scotland moving towards independence?

- Published

Yes campaigners outside the Scottish Parliament building after 2014 referendum saw a majority for No

Opinion polls suggest a consistent majority of Scots are now in favour of independence. What is driving this surge in support?

When Scotland awoke one grey autumn morning in 2014, it seemed that nothing much had changed.

For a start, the weather was typically Scottish - damp, dreary, drizzly - for another, the union with England, which had endured for more than three centuries, remained unbroken.

After years of passionate disagreement, the votes had been counted overnight and Scotland had decided against becoming an independent country by 55.3% to 44.7% - a substantial but not overwhelming margin.

Six more spins around the sun and the independence campaign continues, in a very different world.

The independence campaign continues in a very different world

The UK has withdrawn from the European Union despite a majority in Scotland opposing that move.

A deadly virus has ravaged the globe, leaving more than a million people dead.

Lockdown and other restrictions have left the UK economy reeling, with the UK government borrowing mind-boggling sums to support unemployed workers and save shuttered businesses.

The powers - and limits - of the Scottish Parliament, particularly over health and education, have been demonstrated more dramatically than at any point since they were devolved from London to Edinburgh in 1999.

The contrasting styles of Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson have been plain to see.

Even the climate can be said to have changed.

Research suggests that last year, for the first time, a majority in every age group in Scotland regarded climate change as an immediate and urgent problem. As a result oil, once Scotland's most valuable asset, has gone very much out of fashion.

Opinion polls

Amid all this turmoil, the public mood, it seems, has shifted too.

In the past four months nine opinion polls in a row have indicated that Scottish independence is now backed by a majority of voters, the most sustained period of support for secession in modern history.

One recent survey, by Ipsos MORI for STV News, external, suggested that the "yes" vote had risen to a record high of 58%, excluding those who answered "don't know".

Polling expert Prof Sir John Curtice, of Strathclyde University, says that poll may be an outlier but even so he reckons support for independence is running at an average of 54%.

Sir John has also noted that the gender gap, which saw women more reluctant than men to support independence, seems to have vanished and that increasing numbers of younger voters appear to favour leaving the UK.

Different landscape

Sally Williams says independence has nothing to do with nationalism

"We're in a completely different landscape now," says Sally Williams, speaking in a field on her farm near Earlston, some 20 miles from the border with England.

"Brexit is a huge factor," she adds, explaining why she supports independence, while being jostled by her herd of lowing dairy cows eager for some more feed.

In 2014 the central case against independence was that it would jeopardise Scottish prosperity.

It was claimed that mortgages, jobs and savings would be endangered and that an independent Scotland did not know what currency it would use.

Opponents said it could not possibly raise enough taxes to fund its high levels of public spending and that it would be forced to leave the European Union to boot.

It was largely an appeal to pragmatism not emotion, a transactional rather than a cultural case for the UK. It became known, thanks to an ill-advised joke by one of its advisers, as Project Fear.

Stormy waters

Effective at the time, the message's durability is now in doubt for three reasons.

First, the more that campaigners for the union highlight Scotland's dependence on tax receipts from the richer south east of England, the less attractive such a state of affairs may appear.

Increasing numbers of voters in England are asking why they should be writing the cheques and many north of the border are wondering why Scotland is poorer than other parts of the UK in the first place.

Secondly, it did not resolve widespread Scottish discontent about being ruled, at a UK level, by a Conservative party, which is consistently far less popular north of the border.

Thirdly, and perhaps most obviously, it assumed those British waters would remain calm and the voyage serene.

Instead the seas have been stormy.

'Brexit has put the tin lid on it'

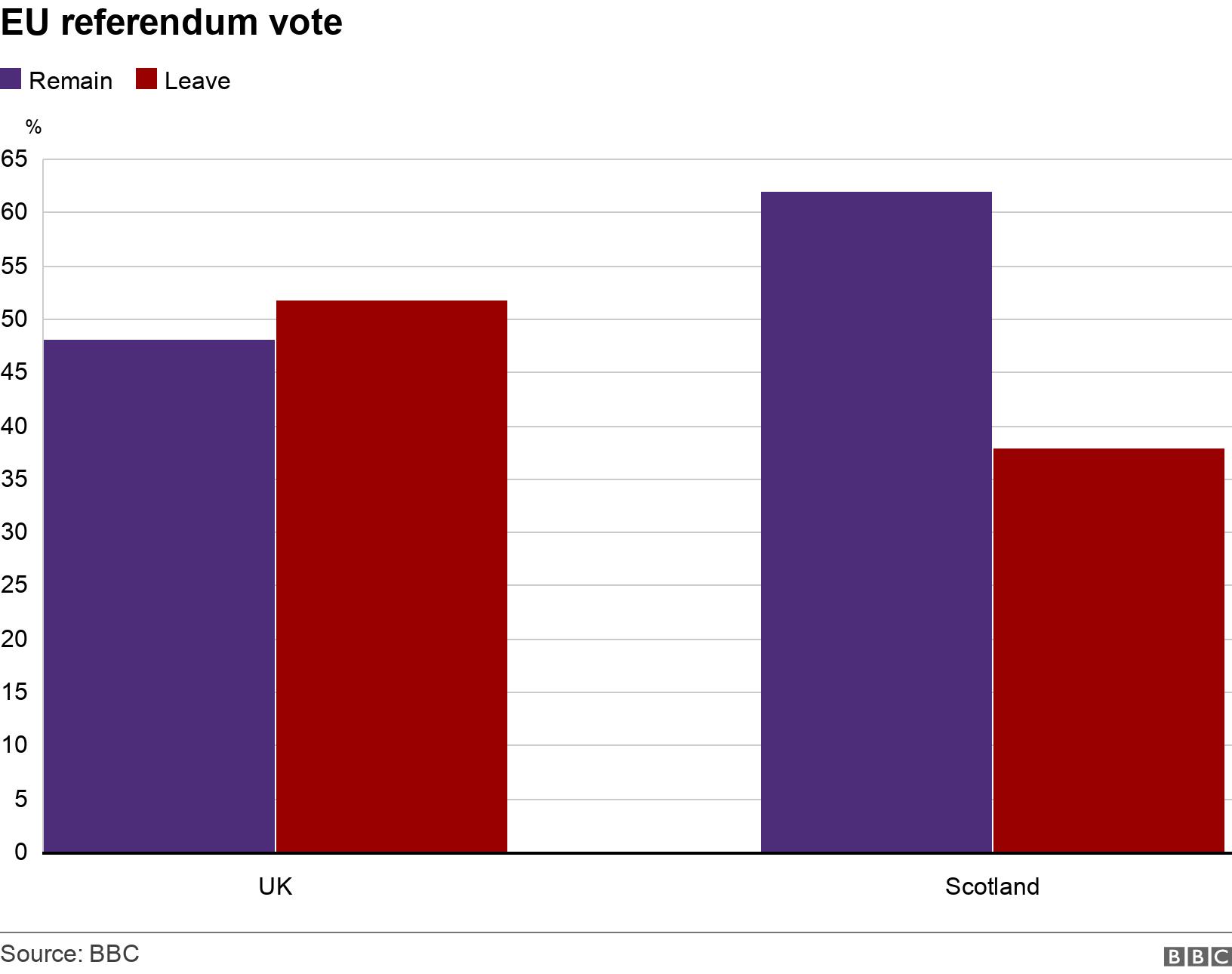

On 23 June 2016 a majority of voters across the UK opted to leave the EU.

In Scotland, the one million people who wanted to leave the EU were far less than the 1.66 million who wanted to Remain.

The leave vote was unaffected by Scotland and Northern Ireland favouring remain, prompting Nicola Sturgeon to declare that there had been a "material change" in circumstances which justified asking Scots whether they had now changed their minds about rejecting independence.

"Brexit has put the tin lid on it for Scotland," says Ms Williams.

"We were told there wasn't going to be a border in Ireland and now who knows how they're going to fix that?" she says.

"We were told there was an oven-ready deal [with the EU], that it would be the easiest deal in history, and we're not getting any of that."

Louder voice

Not far from the US president Donald Trump's golf course on the Aberdeenshire coast, Michelle Stephen farms some 600 ewes and 10 rams (or tups, as they're known in Scotland).

She opposes Brexit and worries about its impact but she does have concerns about independence which are practical and specific.

Michelle Stephen farms some 600 ewes

"We need to know what would happen if we did separate from England," she says. "I think we are better off staying [in the UK] and then we've got a louder voice to make trade agreements with other countries, not just the EU, but other countries as well."

This is the conflicting effect of Brexit on Scotland's current constitutional debate. One argument holds that it strengthens the political case for leaving the UK (Scotland didn't vote for it), the other that it weakens the economic case (why compound the uncertainty?)

The SNP's major argument is that decisions about what is best for future governance are fundamentally different depending on whether you are in London or Edinburgh.

Second referendum

This is the case for independence it is likely to advance in any future referendum.

It wants Scotland to have the ability to implement policies tailored to the specific needs of the Scottish, rather than the UK, economy.

Ms Sturgeon has confirmed that her party's manifesto for next May's Scottish Parliament elections will contain a commitment to a second referendum, or indyref2 as it has become known on social media.

She is hoping to win a majority of seats and the polls suggest that outcome is likely.

But the power to hold a referendum resides with Westminster. The 2014 poll was only arranged when London agreed to temporarily transfer that power to Edinburgh.

Mr Johnson has repeatedly insisted that he will not consent to a second vote but there are indications that some members of his governing Conservative party regard that position as unsustainable, external.

North sea oil

Something else has changed in the past six years: oil.

Since BP discovered the giant Forties field in the North Sea off Aberdeen in 1970, the 'black gold' has fuelled the independence movement.

Most of the UK's oil is in the waters off Scotland

"It's Scotland's Oil" was a rallying slogan for the SNP in the 1970s.

For years the party pointed to prosperous Norway, which used the proceeds of its share of North Sea oil to set up a vastly profitable investment fund, as an example of the wealth an independent Scotland could enjoy.

The UK government, which controls the tax revenue from the British sector of the North Sea, most of which is in Scottish waters, never set up such a fund.

Those arguments have faded as the price of the commodity has collapsed, the industry has contracted, with thousands of job losses in Aberdeen, and the conversation about tackling climate change has made it politically trickier to extol the benefits of fossil fuels.

In the run-up to the 2014 referendum, the Scottish government published a prospectus for independence which mentioned the word "oil" more than 140 times. It predicted North Sea taxation revenues of between £6.8bn and £7.9bn in 2016/17, which it suggested would be the first year of independence.

The actual revenue in that period was less than nothing, minus £24m.

In the Angus county town of Forfar, Owen Foster reckons this was a devastating blow to the SNP's credibility.

'Crash in the economy'

Owen set up a farm shop business with the help of his parents

Mr Foster did something unusual for this year. He started a business.

A few years ago, as a schoolboy keen to earn some money, he had asked his grandmother to teach him how to make jam. Within a week he had sold 50 jars. And in lockdown he went one step further, opening a farm shop with the help of his parents.

The Foster family are no fans of independence.

"Back in 2014 one of the main points that was put to us was the oil industry was going to be one of the big incomes," says Mr Foster,

He adds: "There's just not the money there any more to go independent."

Leaving the UK, he says, would lead to a "massive crash in the economy".

"We don't have the borrowing power that the UK has because it's got the Bank of England. It's got the pound."

'A tale of two cities'

Claire Millar says Aberdeen is divided between rich and poor

On a housing estate in North East Scotland, Claire Millar says the talk of prosperity within the UK and riches from the North Sea is almost beside the point.

In 2014, as an active member of the Labour Party in Aberdeenshire, Ms Millar campaigned for the union under the umbrella of the official "No" campaign, which was styled Better Together, an uneasy alliance of Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat politicians.

She says the black gold did not benefit the poorer parts of Scotland's oil capital. Rather, the profits went to wealthy suburbs and multinational companies while the tax revenues flowed to Whitehall.

Aberdeen, she says, is "a tale of two cities," with a lot of wealth from oil but also a lot of poverty too.

"Just five years ago I hadn't heard of food banks in Aberdeen and now they're popping up everywhere," she adds.

"By staying part of the [UK] we were going to keep our European citizenship. That was the main promise and that's been broken.

"I feel betrayed now because I believed what I was told by the Better Together campaign and the Westminster establishment and what I was telling people on the doorsteps was effectively lies," she adds.

Her mistake in campaigning for the union in 2014, she says, was to assume that Labour would sweep back to power and "sort everything out."

Instead she laments, "we're on the third Tory prime minister."

The Nicola Sturgeon effect

This democratic deficit has been a refrain of the independence movement for decades but it has been given new life by Boris Johnson, who is deeply unpopular in Scotland. , external

By contrast Nicola Sturgeon's opinion poll ratings have soared, external during the pandemic, even among many voters who oppose her party and its aims.

In a leafy suburb in north west Edinburgh, Gail Buckie has just returned from the school run with her two children.

In 2014 she "played it safe" and voted to remain in the union. "I didn't want to take the risk," she says.

But the coronavirus, and especially the First Minister's daily presence in televised briefings and her consistent messaging, has changed Ms Buckie's mind.

"Seeing how Nicola has handled the situation has really made me see that Scotland's a lot stronger than I initially thought it was," she says.

"It feels like we've all really been sticking together, which is something I think we're not seeing in the United Kingdom as a whole," she adds.

Global pandemic

Amy Lee Fraioli has had a change of heart since 2014

While there is clearly movement among Scottish voters towards independence there is also some in the other direction.

Scotland's populous central belt was hardest hit by the virus.

In Lanarkshire, one of the health board areas which remain under tight restrictions, pandemic and politics are colliding.

Since voting for independence six years ago, Amy Lee Fraioli, from Blantyre, has had a change of heart.

Now she works for the Labour Party and promotes the union she once opposed.

"We're in the middle of a global pandemic," says Ms Fraioli. "And had Scotland voted independence in 2014, we would have been very unstable economically at this point.

"We couldn't have given the economic support that the UK government's given", she says, pointing in particular to the Job Retention Scheme introduced by Chancellor Rishi Sunak to subsidise wages of furloughed workers.

So why, then, is support for independence rising?

"I don't think there's any doubt about the fact that it's because Nicola Sturgeon's a fantastic communicator," admits Ms Fraioli.

Communication is one thing. Saving lives and protecting jobs is another - and global comparisons suggest that England, Wales and Scotland have all performed poorly.

A study of 22 industrialised countries by Imperial College, London, found that England, Wales and Spain had the highest level of excess deaths from all causes in the first wave of the pandemic between February and May, external, around 100 per 100,000 people.

After Italy, Scotland had the next highest rate, 86 excess deaths per 100,000 people.

Federal UK

"If you actually look at how well the Scottish government are performing, it's not very good at all," says Meghan Gallacher, a Conservative councillor in Motherwell, pointing to hundreds of Covid-19 deaths of older people in care homes and the introduction of restrictions which she says are harming businesses.

"We shouldn't link the pandemic to the future of Scotland's place within the United Kingdom," she insists.

"It shouldn't be the focus of any government just now to look at the constitution," says Ms Gallacher.

Keiran O'Neill is standing for Labour in North Glasgow at the Holyrood elections

Keiran O'Neill, who hopes to be elected for the Labour Party in the north of Glasgow in May's Holyrood elections, agrees.

Like Ms Fraioli, he has switched from opposing the union to supporting it. Mr O'Neill though wants his party to publicly embrace and promote a restructured, federal UK with more powers for Holyrood and regional parliaments south of the border.

"England would remain a nation, but it would have to be broken up into different regions," he says.

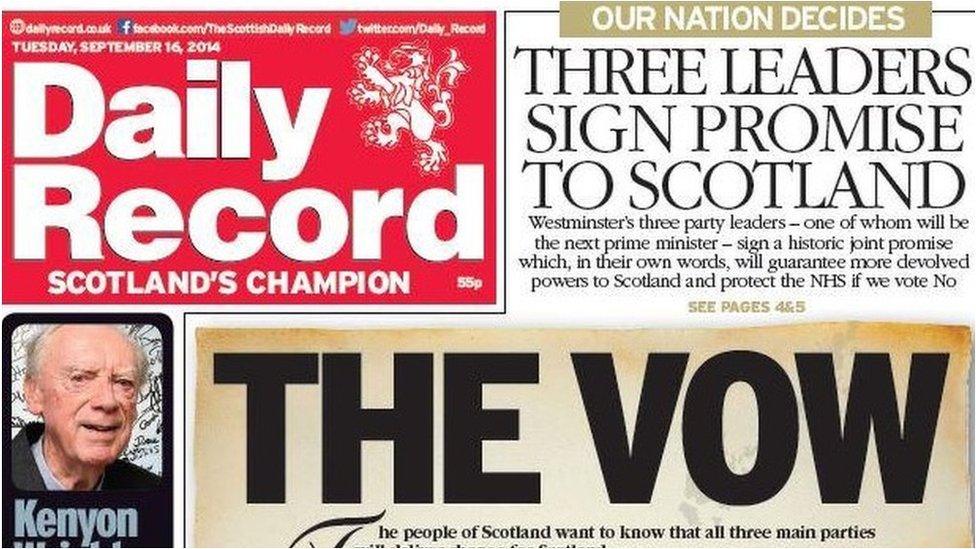

The constitution discussion is not new. Two days before the 2014 referendum, the Daily Record newspaper published a front page headlined "The Vow", promising "extensive new powers" for Holyrood.

It was signed by then Conservative prime minister, David Cameron, Labour leader Ed Miliband and Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg.

Extra powers have indeed been devolved, and used, for example the ability to vary the rate of income tax and the drink-drive limit, external, but the argument about the extent of devolution continues with a fight over the framework for repatriating powers from Brussels and the impact of any future trade deals on the devolved administrations in London, Cardiff and Belfast.

The sustainability of the UK government's position on this issue, and on a referendum itself, is in question.

At present Mr Johnson continues to insist that there will be no second referendum on independence but a leaked policy document reportedly advises the Conservative party that continuing on such a course could prove "counterproductive", external and that the Tories should consider a package of additional powers for Edinburgh if there is a pro-independence majority in May's Holyrood elections.

The SNP, meanwhile, is divided about how to proceed if the prime minister continues simply to say no to a new vote.

Anum Qaisar-Javed wants the power to hold a legal referendum

Anum Qaisar-Javed, a former Labour Party member now attempting to be selected to run for a seat in the Scottish Parliament for the SNP in Lanarkshire, insists the approach must be the same as in 2014, securing the agreement of the UK government for a transfer of the power to hold a referendum from Westminster to Holyrood under Section 30 of the Scotland Act 1998.

"The mechanism has to be in a legal manner," she says. "We can't have an illegal referendum. We can't just declare independence."

But many grassroots members of the independence movement think another option may be needed.

When Mary McCabe started campaigning for independence US troops were still fighting in Vietnam and the Beatles had just released Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

More than 50 years later, she is handing out leaflets in Glasgow city centre as part of a group called Pensioners for Independence.

Ms McCabe wants the SNP to signal in its manifesto for May's elections that it would be prepared to organise its own referendum if Downing Street continues to block one, and that the party should try to win international support for its right to do so.

"By all the rules of self-determination, we should have it as soon as we get yet another mandate," she says.

For Ms McCabe the landscape has changed utterly since she began her political journey in 1967. She points out that the Conservatives, now the main opposition party in the Scottish Parliament, opposed devolution in the referendums of 1979 and 1997.

"People thought the earth would stop turning if we got our own parliament for devolved matters and suddenly they saw it was actually run quite efficiently," she says.

Back in the sixties, she adds she was often in a minority of one in wanting independence. "Now it's mainstream," she says.

- Published14 October 2020