Covid in Scotland: Winter’s fur-lined furlough

- Published

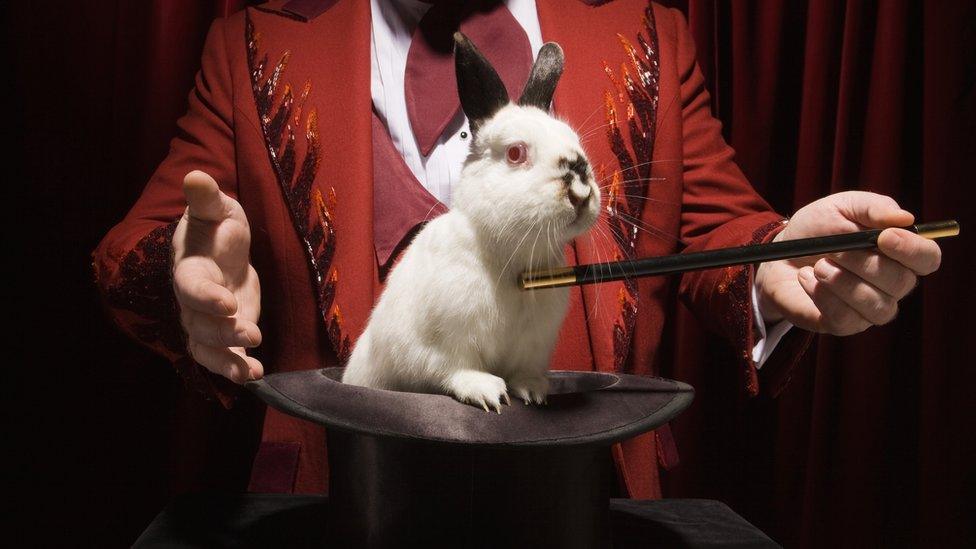

Rishi Sunak produced a rabbit out of a hat with his furlough announcement

Rishi Sunak has eased the tension on the UK's straining bonds by going for the most expensive solution.

That "big bazooka" answers political pressure, but also signals that a bleak winter for the economy lies ahead.

While it's poorly targeted, facing up to the burgeoning bills for the health and economic crisis has this week been punted far into the long grass.

I admit: I didn't see that coming. The UK government continues to surprise, and Rishi Sunak, Chancellor of the Exchequer, is as good as any at producing rabbits from hats.

In this case, again, it's an extremely expensive breed of rabbit. And all to pull off a magic trick of squaring a constitutional circle.

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all wanted flexibility on financial support, to back up the different tacks and timings that they've been taking this autumn on infection control restrictions.

Then the north of England found its voice, having to negotiate optimal health measures in exchange for funding.

The long-scheduled end of furlough on Halloween, at precisely the time when infection and hospitalisation was taking off, was unfortunate, to put it gently.

And no-one could miss the message from across parties, including Conservatives, that the return of fully-leaded furlough less than five hours before it was due to end looked a) rushed b) a very belated concession that the political opposition had been right for many weeks, and c) like unlimited funds are available for the south of England but not other parts of the UK.

Tough winter

That was a truly toxic message in a Union that is straining at the seams under Covid and Brexit pressures. People are affected by these public policy decisions as never before. And the imbalance of South versus The Rest is very easy to understand outside the political bubble.

Clearly, something had to be done. But not many foresaw that the challenge would be seen off by firing the big bazooka of all-UK public spending.

The powers that be are preparing for a tough winter

That tells us something about the politics. It also tells you something about the UK government's approach to public spending.

One week, it was trying to apply the brakes over short-term provision of free school lunches in England: the next, it was lurching forward on full throttle, with a fresh tankful of borrowed money to get it through the winter.

Add to that £150bn of freshly-minted electronic moola from the Bank of England, and you can sense that the powers-that-be in London are preparing for a very tough winter in the British economy.

Test and trace

One reason full-blooded furlough has returned is that it has worked in its primary purpose: keeping unemployment down. It can do that again, though it's too late for many who have already lost jobs from the tapering effect since August.

But it's far from being an efficient use of public funds. By removing any need to justify the use of furlough or of self-employed income support, it splurges money where it's not needed.

And it still fails to direct funds at the millions of self-employed people who don't qualify for support, other than welfare benefits.

Mr Sunak said the extension would give businesses security through the winter

With that announcement came more money for English councils and health services. As a consequence, a further £2bn was magicked up for the devolved administrations.

Holyrood gets £1bn of that, to add to the £7.2bn already added to the 2020-21 block grant due to the Covid crisis. So that's in addition to the UK's directly-funded income support and business loans and grants.

Much of the £8.2bn is going into the health service, testing and tracing, protective equipment, public transport subsidy and grants to business, fed through local councils.

But because it's not clear how it is calculated, it removes one of Holyrood's favourite political games - of boasting that funds are being fully passed on to the health service, to business or whatever or, on the opposition side, alleging that English public services appear to be getting more.

Day of reckoning

Challenged by the SNP's Treasury spokeswoman, Alison Thewliss, the chancellor responded that Holyrood has control of income tax. So if it wants to spend more than it's getting, he pointed out it can use those tax powers.

This is political mischief, of course. Rishi Sunak is able to borrow rather than having to use tax levers. There's a consensus that using them now would sharply slow the economy when that's the last thing it needs.

The day of reckoning will surely come. Until then, very low borrowing costs can be tolerated while government debt piles up.

The reckoning does not look likely ahead of the next financial year, which starts the week this furlough extension ends, and a month before the Scottish Parliamentary election.

Neither Conservatives nor their opponents will wish to spell out the consequences of vast deficits and burgeoning debt while there's an election looming.

That question of tax and/or spending cuts has this week been punted into the distant long grass.

- Published5 November 2020

- Published5 November 2020

- Published3 November 2020