Covid in Scotland: Retail's bleak midwinter

- Published

How will retailers reflect the pandemic in this year's Christmas advertisements?

Christmas is shaping up to be like no other for retailers, who were already going through a radical restructure.

Enforced closures and home delivery of groceries have been pushing more transactions online, while costs and jobs are being cut, and there are widespread battles with landlords over rent.

As Edinburgh Woollen Mill joins the casualties, the challenge is either to double down on food sales, or think outside the shopping trolley.

Building layer upon layer of tradition, the pre-Christmas TV advert is now some kind of cultural event. Or so the advertising industry would have us believe.

Opinion research shows that advertising is an important signal to get us into the festive mood.

This year is a tough one, reports trade website The Drum, external. Planning for these events began long before the pandemic arrived. And once it did, how do retail advertisers reflect the unique circumstances of festivities in a pandemic?

It's tricky to celebrate the bringing together of families when that's what they probably cannot do this year. So is it fantasy, a child's point of view, or humour? In an economic crisis, is this any time to be pushing luxury purchases?

And how much do they have to spend? The estimate is of a cut by more than 10% in the money being spent on advertising this year.

And that reflects the deep crisis that conventional retail is facing, as it heads into a vital time of year. Non-essential shops are re-opening in Wales, and are newly closed in England, for four weeks, when it would hope to be shifting pre-Christmas stock. Footfall remains very subdued in Scotland.

Rent battles

The past few days have also cost thousands more jobs in British retail, as it adjusts to both a pandemic and the long-term trend away from conventional shops.

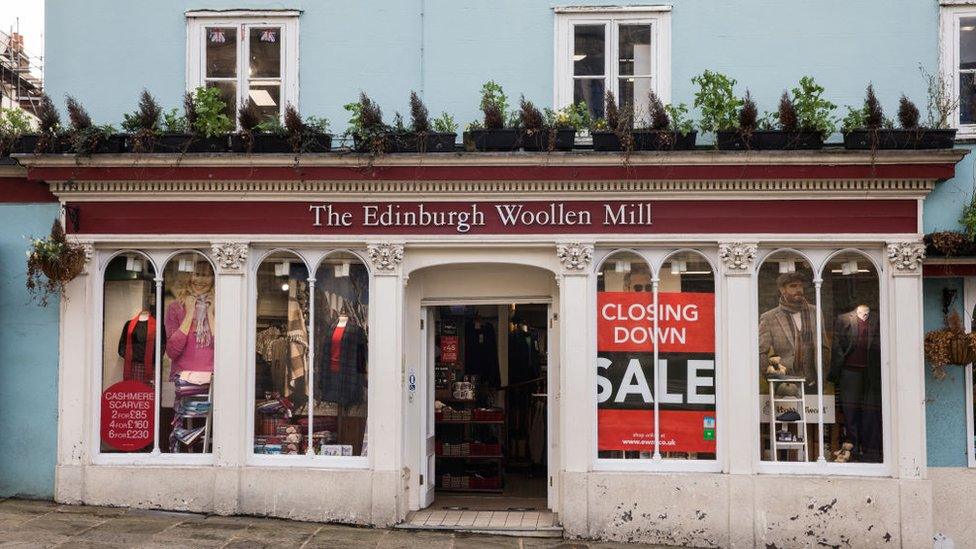

The latest casualty - not unexpected - is Edinburgh Woollen Mill, founded in 1947, and taken over by Philip Day in 2002 as the starting point for building his billion pound retail empire.

It doesn't have much to do with the Scottish capital these days. Headquartered in Carlisle, it imports most of its low-margin line in knitwear and other clothing.

It had carved a niche, but it was the wrong one for a sustained pandemic. Older customers are not venturing out for non-essential woollens these days. And coach parties aren't going anywhere, least of all the tourist destinations where Edinburgh Woollen Mill could often be found.

Edinburgh Woollen Mill is one of the casualties of the Covid lockdown

Of its 284 outlets, 56 have not re-opened after lockdown. Put into the hands of administrators on Friday, 750 jobs are to go out of 2,571. A similar fate has befallen EWM's Ponden homeware chain, with 116 job losses. And that's just for a start.

Philip Day is battling to get most value out of his much larger Peacock's chain of stores, with the higher end Jaeger brand also given a further two weeks by the High Court for the group to find buyers. Much of that battle is to do with commercial landlords, threatening them with store closures if they don't lower rents.

That's in common with numerous other retail chains. Mike Ashley, the retail entrepreneur who has expanded Sports Direct into Frasers department store chain, is still sitting on many outlets with the threat of closure hanging over landlords who would struggle to find other uses for the property.

England's renewed lockdown of non-essential shops has added to their woes, and provoked a classic Ashley grump against government, and Michael Gove in particular, for the restrictions imposed on retail. You may recall he started the spring lockdown in a spat with the government about essential retail and whether that included his leisure wear outlets.

Argos shuttered

Beyond that, it's been a horrible week for Marks & Spencer, reporting its first loss in more than 80 years as a public company.

J Sainsbury, one of the big grocery retailers, and owner of Argos, announced 3,500 jobs are going as it revamps the non-food retail chain. At the same time, it has been taking on numerous jobs, mostly temporary, to cope with the sharp increase in online shopping. Covid-19 has added £290m to its costs, mostly offset by the fiscal-year business rates holiday for retail.

The grocer's Edinburgh-based banking arm was rumoured for a sale. With exceptionally low interest rates, there aren't many profits to be had in banking. Nor are there many buyers for bank assets such as Sainsbury's Bank, so it remains on board for now.

A large number of stand-alone Argos stores have been ear-marked for permanent closure

It was Argos that took the brunt of Sainsbury's change. The catalogue pioneer in the 1980s, which has stopped producing its printed catalogue, is also to cut back sharply on its standalone stores.

Argos was bought by Sainsbury in 2016, and had 583 stores. The plan is now to reduce that to only 100 or so by 2024. That means a lot more empty shops at the brasher and bleaker end of the retail street. The Argos proposition is being shifted inside Sainsbury stores.

Those 3,500 job losses also pull down the curtain on the theatre aspect of supermarket retail. On the periphery of superstores, meat, cheese, fish and pizza counters hark back to the days of a more personal touch, a chat and some advice on cooking times.

But they're not adding much value. Driven to compete on price, that's just what Aldi and Lidl are not doing. So Sainsbury's can't afford to do it either.

Buy back or take back

John Lewis department stores, which is attached to Waitrose groceries, is shedding 1,500 staff, mainly from head office.

With its unique ownership model, owned by its own staff, the John Lewis Partnership has the opportunity to think longer term than others. And it has to do so.

Under pressure from online retailers, it has ditched the claim made since 1925 to never knowingly being undersold - on price, that is.

Last month, having refused to pay a staff bonus/dividend for the first time since 1953, it set out a new strategy that moves it out of dependence on conventional retail.

Online is projected to reach more than half of John Lewis turnover within five years, and account for 40% of profit. Waitrose has this year increased its home delivery capacity by more than four-fold since the start of this year.

In comes a plan to embrace the circular economy, taking on a trial of renting rather than selling furniture. By 2025, it wants to have a proposition across its ranges of "buy back" or "take back".

To develop its homeware offer vertically, it's making a bold move into home building for rental.

Expect more like this. Retail is going through a crisis unlike any it has seen before. It has developed extraordinary efficiency in its supply chain. It has embraced the online revolution and home deliveries.

The option now is to double down on the resilient food market, with its tough price pressures, or to think outside the shopping trolley.