Brexit hits a snag

- Published

Snag tights has captured the size-inclusive market

The textiles sector is already having to prepare for a "no deal" Brexit. In the case of one fast-growing Scottish firm, that means putting UK prices up by 12%.

Even with a deal, it's too late to unravel some of those preparations, and the sector warns many companies are not yet aware of extra paperwork and regulation.

With less EU trade, there are hopes of trade deals with other countries. But instead, Monday saw an escalation of the EU-US trade dispute over aircraft manufacturing which has snared Scots cashmere and whisky distillers.

Snag Tights were born in the Brexit era. Less than three years ago in West Lothian, Brie Reid and Tom Martin started up the company, having spent a long time finding the right manufacturer.

They found it in a family-run textiles mill in Italy.

They chose West Lothian as their base for its relatively low price rental, reliable, low-churn workforce, motorway access and courier collections that can get the product to American customers faster than some can manage in the US.

And the product? Bright and funky coloured tights, with special editions and fun names: Builder's Tea, Bloody Mary, Blue Hawaiian, White Russian, Fishies and Sharkies.

Its website does not feature the typical underwear model. Seven sizes range from 6 to 36.

It has won a lot of word-of-mouth recommendations and repeat business for a product at £7.50 per pair. Marketing is largely through Facebook, and an online community, where enthusiastic fans are known as "Snagglers".

Size inclusive

Brie Read had done her market research, with figures showing 90% of women can't find tights that fit them properly. "Sixty per cent of women are now over size 16, and the fashion industry doesn't cater for these people as it should," she told me.

"For us, the dream is to be completely size inclusive, so everyone of every size should be able to buy the same clothes, and have tights that fit".

Only 30 months in, the company is sending out 4,000 parcels per day, to 90 countries, and turning over £3m per month. They now represent 60% of their Italian supplier's production.

With 70 people on the payroll now, they want to take on more - up to 100 more. They're on a rapid "land grab" of this "size-inclusive" market, before others can catch up.

Going Dutch

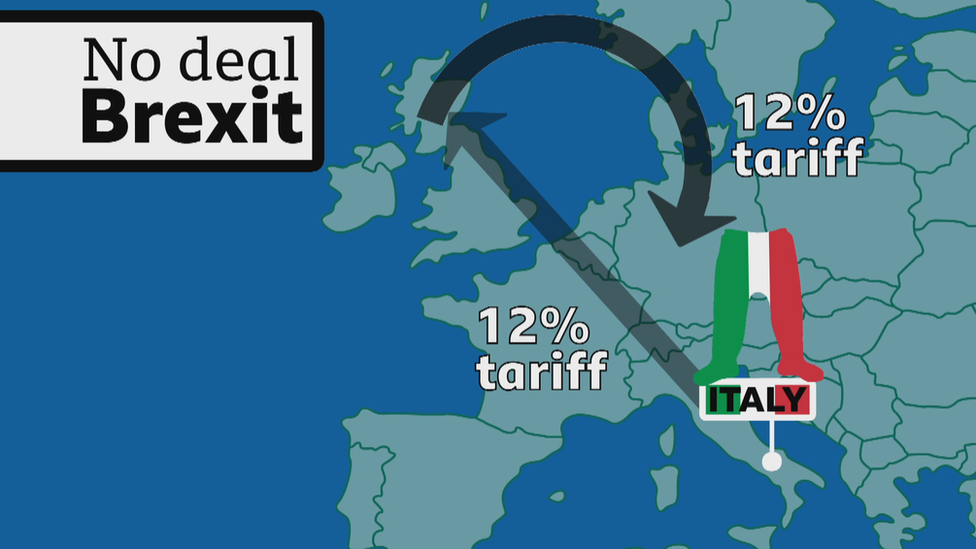

But there's a snag. Two of them, in fact. One: A "no deal" Brexit at the end of next month means that their tights would be imported from Italy with a 12% tariff.

The UK has said it plans to impose that on finished garments, to protect UK manufacturers from low priced competition- just as the EU has been doing. Fabric gets an 8% tariff and yarn is on 4%.

For Snag, that tax will be passed directly on to the UK customer - roughly 30% of their market - with an explanation on the website and with a receipt explaining that the charge is a Brexit tax, which benefits neither the seller nor the customer.

And two: Around a third of the market is in the European Union. To send from post-Brexit Britain into the EU would carry another 12% tariff.

That makes no sense, so on 1 December, they open a new distribution centre in the Netherlands. They don't expect to shed any jobs in Scotland, as business is growing fast.

A "no deal" Brexit means Snag tights woud be imported from their manufacturer in Italy with a 12% tariff and the same would be added on when they are sold back into Europe

Snag would have preferred to grow in Scotland, but two potential tariffs of 12% meant it had to go elsewhere. So remaining within the world's biggest single market, the Dutch town of Venlo gets the jobs benefit of this business success. From there, they will also fulfil orders for non-EU countries, including the USA and Australia.

"Left entirely alone"

Of course, there could be a deal, and that would probably mean tariff-free trade. But it's come far too late for a company that couldn't put its growth on hold while the political Brexit can was kicked down the road.

"Those are jobs that would have been here in Scotland, if it hadn't been for Brexit," says Read. "Now, they're going to be in Europe. I'm very happy we'll be able to offer the people of Venlo jobs, but I would have rather they'd have been here."

She reflects: "It's been really difficult, particularly over the last year, because we've been expecting some movement in terms of whether there will be a deal or not.

"But so little movement has happened. We've had to take it entirely into our own hands and that feels very unfair - rather than having any advice or expertise or anything from the government about how this is going to happen.

"It feels like we have been left entirely alone just to do what we can. That's not how you want to grow a business and that's now how you make an economy work."

Fashion runway

Importing garments from the EU and selling back into it has put Snag Tights in a particularly difficult place. But it's not alone, in a UK industry employing 120,000 people, turning over £9bn, and with three-quarters of its exports going to the EU.

According to Adam Mansell, chief executive of Textiles Scotland and also of the UK textiles and fashion trade body, larger companies that sell into Europe have been making similar plans.

Snag are sending out about 4,000 parcels a day from their warehouse

Smaller companies, of which the fashion industry has many, are much less likely to be prepared for what may hit them soon. Even taking some garments to the Paris Fashion Show for a couple of days next year, he points out, will require an export certificate, and these companies have never had to think about that before.

If the proposed level of tariffs is charged on all the garments, fabrics and yarn sold from the UK into the EU, the trade association reckons it could add around £1bn to prices. Brie Read asks where that tax revenue is going, and could it be recycled to help the firms affected?

If there is a deal, with no tariffs, there is still an expectation of much more paperwork and requirements on labelling. Some goods that are made from yarns and fabrics imported from outside the UK and EU would still have tariffs at varying rates, when finished garments are sold into the EU.

"Global Britain"

And there will be labelling requirements, where there are dual licensing for safety and for use of chemicals.

"The export paperwork will still apply in the event of a deal," says Adam Mansell. "There will still be borders and the need to have the right paperwork. They'll still need the right labelling. And with intellectual property and design rights, you'll have to protect them in the UK and the EU.

"We very much hope there will be a deal, but even without a deal, it will be a completely different trading environment. Companies are going to have to learn to do things twice".

Brie Read would have preferred to create job opportunities in Scotland but she says Brexit has made that more difficult

There is a potential "global Britain" upside to Brexit, if the UK can secure trade deals that reduce tariffs on exports to other countries. The USA, for instance, has tariffs of more than 30% on finished garments, and is a ready market for luxury goods.

"It's an incredibly expensive market for our exporters to break into. So if we can get a free trade deal with the US, that would be a huge advantage."

Cashmere and Scotch

First, though, there is the hope that a new Washington administration will remove the punitive 25% tariffs on cashmere sweaters, aimed at the Scottish industry while allowing Italian rival products in to the US with no tariffs.

Along with the same level of tariff on single malt Scotch whisky, imposed 13 months ago as part of the dispute between the US and EU (along with the UK), over subsidies for Airbus in Europe and for Boeing in the US.

That dispute escalated on Monday, with the EU imposing a 25% tariff on nearly £3bn-worth of US exports, ranging across tobacco, nuts, fruit juice, fish, spirits, bags, tractors and casino and gym equipment.

The intention of the EU is to match the position of the US Trade Representative, using that leverage to force Washington into talks on a resolution.

New faces in charge in America may help lower the temperature and re-set relations. But the dispute pre-dates Donald Trump's presidency. And it would be just the first step towards a much more complex question of securing a US-UK deal, in which food and agriculture will weigh more heavily than Harris Tweed jackets.

- Published24 October 2020

- Published25 September 2020