One month to Brexit: Counting the cost of 'no deal'

- Published

MIchel Barnier, the EU chief negotiator, arrived in Westminster for further Brexit talks on Sunday

The UK government's official, independent economic advisers have set out some stark warnings on Brexit without a European Union trade deal, including sustained lower levels of economic growth, inflation and higher prices.

It makes it more difficult to sustain the prime minister's claim that Britain will "prosper mightily" without a trade deal.

As crunch points have come and gone, the eventual decision on "deal or no deal" is coming down to the European Union's judgement on whether Boris Johnson is bluffing about his willingness to accept higher levels of economic cost, or if he's ignoring them.

The deepest recession for more than 300 years allied to the biggest risk ever undertaken with the British economy, as it exits the European Union: yes, this is the winter of the Covid-Brexit double whammy.

Yet Brexit was absent from the Chancellor's spending review statement last week. It was not absent, however, from the report by the Office for Budget Responsibility, external, deliberately coinciding with the Treasury plans.

You have to reach page 193, but it's worth a look, given that the end of the transition out of the European Union is just over 30 days away. Discussing the WTO or World Trade Organisation rules (which the prime minister prefers to call "Australian", perhaps because it seems less bureaucratic), you'll read why the Chancellor might not want to talk about it.

The report looks at different scenarios for both Brexit and for the course of the Covid crisis. On a "no deal" WTO Brexit, it assumes border distortions and delays, and at new trade deals being done (of which more later).

It assumes fiscal policy on tax and spending isn't much changed, though warns that a further slowdown in economic activity would push more people into furlough and more companies into default on their new government-backed loans.

It assumes little shift in monetary policy, except that inflation could go up as a result of a dip in the value of sterling, allied to new tariffs on goods imported from the European Union, pushing prices up 1.5%.

It's noted that the sectors hardest hit by Covid-19 - hospitality, tourism, travel, etc - are not the ones that would be hardest hit by a hard Brexit. That's where manufacturing supply chains are stressed to breaking point, notably in the car-making industry.

A warning last week from the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders argued that "no deal" looks like costing the industry £110 billion, split equally between the UK and the EU auto sectors.

Brexit was absent from Chancellor Rishi Sunak's spending review

As UK car makers rush to grab a share of the electric vehicle market, tariffs would put £2,000 on the cost to an EU customer, and £2,800 on an EU car coming in the other direction.

As we should know by now, cars are multi-national in their many components, repeatedly crossing the English Channel on the journey to the showroom.

Even with a no tariff deal, and the new complications of trading, the hit to the industry is estimated at £14 billion. "Brexit has always been an exercise in damage limitation," says the SMMT.

The WTO outlook, according to the OBR, is for a further 2% reduction in output next year when compared with a managed and agreed no-tariff deal, easing off to a 1.5%, and then stabilising at around 2 percentage points below the level of output that would be otherwise be achieved.

With that comes a forecast of unemployment going up by 300,000 over the next two years, before that impact declines, but remains at a higher level than it would have been otherwise.

Lower productivity

The OBR acknowledges that it's not the only one in the forecasting business. Nor, point out Brexiteers, does it have the strongest of track records with this.

So it lists 13 other studies of the impact of a "no deal" Brexit, carried out over the past four years. The average puts growth, with an EU no-tariff deal, at four percentage points behind the level of growth that could be expected within the European Union. With no deal and with tariffs, that rises to a gap of 6.1 percentage points.

The reasons are partly through the initial loss of jobs and companies failing because more expensive access to EU markets undermines their business model.

Over time, the more significant effect is lower productivity, from having less pressure to compete and less influence from the most efficient EU companies, and then also from lower business investment.

The hope is that the UK will strike better trade deals outside the European Union. That's less likely if the UK government has to follow through on its threat to break the protocol on Northern Ireland. It will probably be harder to convince others that Britain is as good as its word in negotiations, and Ireland's allies, including the USA, are strongly critical.

So far, there have been several agreements signed, which ensure the current arrangements with other countries are continued after December 31, such as Canada, South Korea, Israel and Morocco. There are agreements with Norway and Iceland, with plans to open up new arrangements for shared fishing stocks.

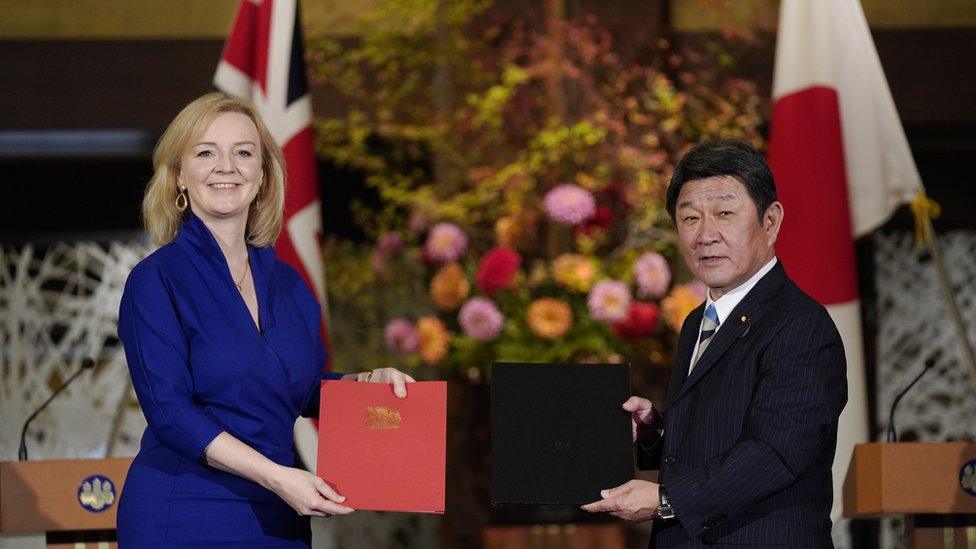

There was also a deal signed with Japan, hailed by international trade secretary Liz Truss as an improvement on what had gone before.

Committees of the House of Commons and of the Lords separately looked into her claims, and both concluded that she appeared to be exaggerating. The elements that appear to be better - such as protection for geographical indicators of British products (think Stornoway black pudding) - are yet to be nailed down.

Liz Truss signed the deal with Japan's Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi

And the final sticking point, on exporting UK cheese to Japan, was agreed without an increase in Japanese import quota. Instead, it gave Britain the right to tariff-free exports, only so long as the EU quota hasn't already been used up. UK cheese exporters have to wait and see if there are leftovers, which removes any predictability about pricing.

The big prize remains a trade deal with the US, or so we've come to think. But the OBR brings a reminder that the gains may not outweigh the political pain of arguing about chlorine-washed chicken and a potential threat to let US healthcare into the NHS. It points to the government's own estimates of the added growth from a trade deal are very modest.

All that is worth bearing in mind when the prime minister reassures us that Britain will "prosper mightily" when it departs the EU single market. That depends what you mean by "mightily".

It could be that it prospers, in that the economy continues to grow, but in the short and medium term, it is not expected to prosper as it would have done inside the European Union.

What Mr Johnson is clearly trying to get across to European negotiators is that he is relaxed about walking away from talks. If they're convinced of that, they're more likely to give ground.

Flexible schedule

As things stand, the EU has less to lose from a "no deal" Brexit, at least relative to its size. Given that weaker negotiating position, Britain has to show willingness to accept pain. Boris Johnson's approach is to feign (or perhaps to concede?) his ignorance of how much pain that would involve.

The EU's task now is to judge whether he's bluffing.

The crunch points for this began last June, and have become more frequent in recent weeks. We were thinking that they had to leave time for the European and UK parliaments to pass the necessary legislation, but that also appears a flexible schedule, and could mean legislators' Christmas plans become even more complex.

The two sides remain stuck on three issues: whether Britain has to play by European rules on support for its industries if it's to have access to European markets. That's about subsidies, and about Europeans wanting to ensure they're not undercut on their standards for environmental, social and labour market rules by Britain doing things more cheaply.

It goes further than that, and the question of whether Britain can be required to follow changing European standards, when it doesn't yet know what they'll be, and won't have influence over setting them.

What's been hard for European to judge is whether Britain is heading towards deregulation, to reduce business costs, or towards much more state intervention in the economy. Boris Johnson seems to be heading in both directions at once.

There's also the question of governance, which is a lot to do with the rules for settling disputes.

And then there's the fishing industry - with big expectations raised in Scottish and south-west English port towns, but similar determination also in those of France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Spain.

Things may yet founder on this relatively very small, very localised part of the economy, even if the price paid by manufacturing exports, like English-built cars and the wider food sector, is far greater than any gain from pushing all foreign boats out of British waters.

There's clearly an interest for Scottish salmon farmers, creel fishers and fish processors in getting quick access to big, lucrative European markets.

Britain doesn't have either the size of fleet to pick up on the fishing opportunity that could be created, nor the coastguard fleet to defend its waters against encroachments, which would be very expensive.

Will the PM compromise?

We heard in the past few days there could be compromise here, on the timing of a limited European retreat from what has been a very large share of tonnage from UK waters, and the percentage reduction we might see at first, reported as 15 to 18%. Bigger reductions could be achieved over a long period.

That may not be acceptable to the UK, but if they're talking numbers, they've moved beyond assertion of principle, and that could be a positive sign of movement towards a deal.

What the British side wants the Europeans to acknowledge is that Britain has secured the right to assert its sovereignty.

The European side wants Britain to recognise that sovereignty has to be traded away if it wants to trade with others. It also has to give ground and share power if it wants the co-operation of others on things that are to Britain's benefit - access to the energy market, rules on the environment, security and defence.

If Boris Johnson does choose to compromise, he may find it hard to pivot his own side of Brexit hardliners for that to happen. And given the way Tory MPs are talking with some disdain about the prime minister's rules on infection control, he seems to lack authority with his own people. So getting compromises agreed at Westminster at this late stage could prove challenging.

- Published25 November 2020

- Published25 November 2020