Scotch whisky: 'Leveraging your passion points'

- Published

Scotch whisky exports have been hard hit by the closure of bars and restaurants, in markets around the world where these dominate drink consumption.

The value of exports has been harder hit than volume largely due to the loss of super-premium sales at airport duty free, and because of US tariffs.

Distillers have pivoted to sales for drinking at home, but Scotch is vulnerable to consumer trends that have put rocket boosters under rival spirits.

Conviviality: the factor we crave in lockdown and recreate in on-screen partying. It's driven a big rise in off-licence and online sales of spirits in recent months, adding some sophistication to the occasion.

So we're told by the magicians of whisky marketing. They've had to move swiftly with Covid in those many markets around the world where Scotch is more often consumed in bars, clubs and restaurants.

I actually heard one such wizard this week talking, with a straight face, about "leveraging our passion points".

In contrast with the British dram from a bottle or three kept at home, Scotch whisky is marketed as the drink of choice in American up-market bars, from golfing country clubs to New York sophisticates.

It's sold long with mixers in South America and Spanish late-night clubs, as a French aperitif before dinner, and a signal in Chinese bars of aspirational, international horizons.

Scotch whisky's marketers display world-class skills in promoting the mystique of its provenance, handling the potentially confusing divergence of its many brands and expressions, while breaking down barriers to "recruitment" of new whisky drinkers.

For instance, Ballantine's, one of Chivas Brothers' big international brands, is sold with the reassurance to drinkers: "There's no wrong way... stay true" - to the quality and provenance, and to yourself.

Travel channels

Much of this recruitment, in normal times, is done as an experience in the controllable environment of bars. But widespread closures of the on-trade in the past year have savaged export sales, contributing to a £1.1bn fall in the value departing the UK last year, dropping to £3.8bn.

Hence, the pivot to home consumption, promoting Scotch through retail and online sales. This week, I spoke with Jean-Christophe Coutures, chairman of Chivas Brothers - which is owned by French drinks giant Pernod Ricard - as he talked up that "conviviality" message through online meet-ups, lubricated by spirited cocktails.

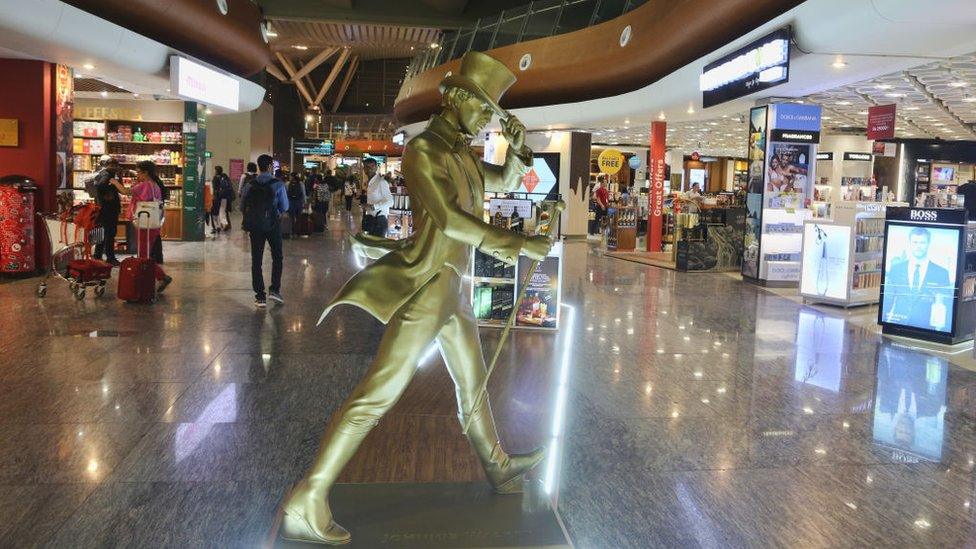

The loss of super-premium sales at airport duty free has hit whisky distillers hard

The company reported online sales up 138% in the UK, but still under 10% of the total. Glenlivet off-sales in Britain were up 48%, Absolut vodka by 38%, Jameson Irish whiskey up 27% and the newcomer star was Malfy gin, up by 151%. The company reported off-sales of its wine range up 17%, "in line with the market".

There may be a permanent shift in the way people drink and socialise, says Coutures, but there's also an assumption that people will be super-eager to get back into bars when they're allowed to, so the pivot back to the on-trade is being readied.

Chivas - which produces Chivas Regal, Royal Salute, Ballantine's and Glenlivet - tells us that the more home-based UK whisky market saw 31% growth last year. Eastern Europe, notably Russia and Poland, also with more home-based drinking, saw 10% growth. But western European sales were down 12%. The huge French and Spanish markets for Scotch are, in a normal year, half on-trade.

Worldwide, the company saw a 10% decline, but almost all of that can be accounted for in the so-called "travel channel", or duty free shops, mainly in airports. With far fewer passengers, that was down 70% last year.

Trading up

It's an important area for marketing and promoting Scotch in general, but for Chivas Brothers in particular, where a fifth of its sales are accompanied by presentation of a boarding pass.

Duty free is also the place where the super-premium sales are strongest. Next time you're in an airport, check out the display, and you'll find lower-cost blends are hard to find and "entry level" single malts are marginalised.

The display will normalise the idea that the gift you're buying, perhaps for yourself, has to be of an exclusive rare expression by age, cask conditioning or simply branding and packaging, at two to three times the price of the standard brand.

That is one of the main explanations for the large gap - identified by the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) from HM Revenue and Customs data issued on Friday - between the 13% fall in the volume of Scotch exports last year, while the value fell 23%.

In recent years leading up to 2020, growth has been at the premium end, notably with single malts. Drinkers have been trading up from (typically) cheaper blended Scotch. So value has been rising faster than volume. But last year, the drop in airport duty free sales hit the super-premium brands hardest, so it was value that took the bigger knock.

Tariff retaliation

Big sudden shifts in drinking habits, enforced by the closure of the on-trade, create an opportunity for marketers, but also a risk for a product that enjoys global leadership in the distilled spirits industry.

It exposes the vulnerability of Scotch whisky to spirited competing products. The UK has seen a gin boom in recent years. In the US in particular, "sheltering in place" (lockdown) has put rocket boosters under tequila sales.

And in the US market - the world's biggest for Scotch, by value - those 25% tariffs imposed on single malts in October 2019 (in retaliation against UK and EU subsidies for Airbus) are the third big explainer of a year when all the big gains of the past decade were erased.

The SWA recently said that 16 months of the tariff had reduced exports by half a billion pounds, and the signals so far out of the Biden administration in Washington tell us that the tariffs are not going to be reviewed for at least six months.

The tariff impact has been uneven across distillers. It's not clear that single malts have lost out to non-tariff blends. The big players have kept up sales, if not market share.

They've adapted, and they may have absorbed some of the tariff cost. Jean-Christophe Coutures explains that his company's Glenlivet has held up as a $30 entry level single malt.

But listening to Diageo, Chivas Brothers and the SWA, the concern is for smaller Scotch exporters, whose consignments are treated by US distributors as a tariff-laden problem they can do without. Even though Scotch blends don't carry the tariff, they can be caught in wholesaler reluctance to deal with tariffs at all.

According to Monsieur Coutures, a member of the SWA board, there's a real risk where the business model is built on US exports, that smaller distillers back in Scotland may no longer be viable.

If so, the investment and expansion of capacity continues, laying down stock for consumption long after the Covid crisis has passed. But there could be some blending to be done by corporate consolidation.