Scottish election 2021: Many manifestos, but for what?

- Published

A lot of work goes into election manifestos. They may not be read by voters, but they matter.

The Holyrood election shows there is more convergence and consensus than divergence and dispute on what is required for the next five years, apart from one big issue.

It is worth considering what they don't include, as much as what they do, and watch out for messages that are less about winning votes but also to warn the public about change ahead.

The sixth Scottish Parliament elections, with less than two weeks to go, will surely be remembered as the Covid campaign - fought with lockdown and social distancing between candidates and voters.

The result may be decisive, either way, for the independence movement.

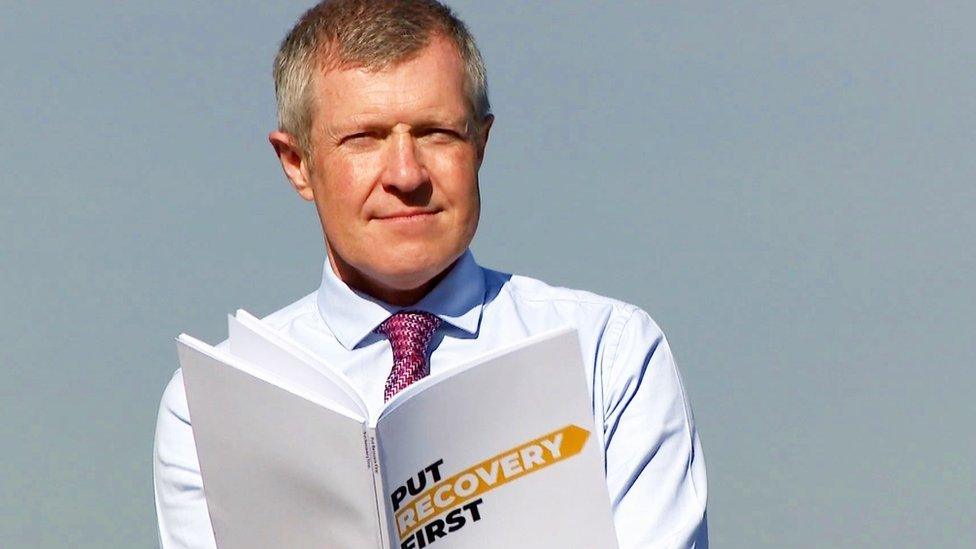

But with all the manifestos now published, what do they tell us about the broader challenges, the pressures and the decisions that lie ahead for MSPs elected on 6 May? Having read the main parties' manifestos, here are some themes.

SIGN UP FOR SCOTLAND ALERTS: Get extra updates on BBC election coverage

Manifestos matter

Compiling a manifesto usually gets a lot more attention within a political party than it does within the electorate.

That can be because that's where tensions get resolved inside each party. Labour has long specialised in factional battles over what goes in and what comes out.

Or it can be to establish a mandate for pushing certain policies once elected. A manifesto can be an important element in reaching a coalition deal, though we haven't had one of them at Holyrood for 18 years.

For a governing party, it sets out priorities. And at Holyrood, it becomes the programme of work for ministers, and a way of enforcing discipline in government ranks. If something's in the manifesto, it's much harder to rebel against it.

So manifestos matter. And they're an important guide to our politics and priorities in public life.

The main ones don't differ that much

At considerable risk of generalising, I'm struck by how parties approach a narrow range of big issues in similar ways. On reading them, you don't get a sense of markedly different futures.

Even if you take Scottish independence as the big fault line, the argument in this campaign is not what it would look like but whether there should be a referendum. The different portraits of a future Scotland that the main parties sketch out in these manifestos are not that different.

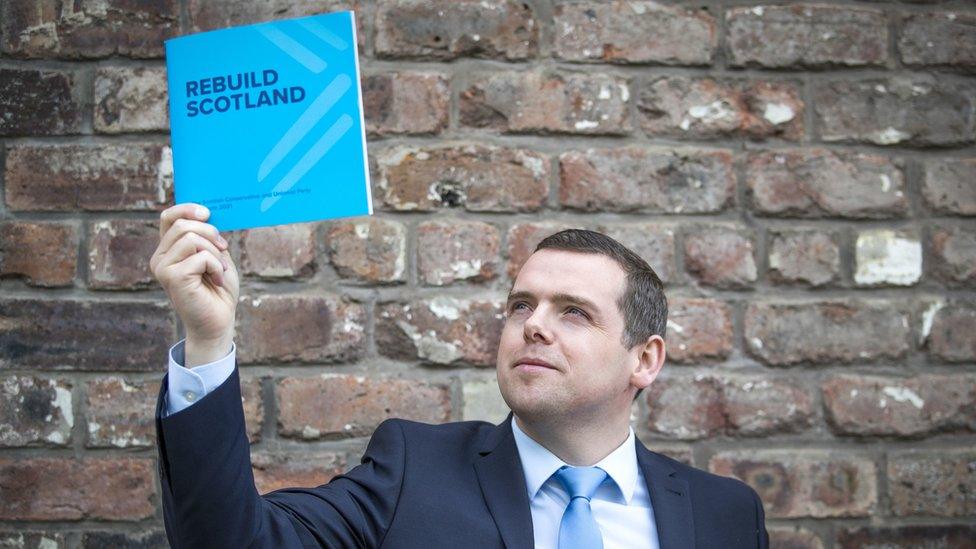

You might expect Scottish Conservatives, for instance, to have a clearly different view of the role for the state in people's lives. That's not what you get. Tories have moved into the consensus area where things are provided for free to everyone, including student tuition, prescriptions, school meals. (Twenty years ago, when Tommy Sheridan proposed free school meals, other parties saw that as too radical.)

(This reflects on the five main parties. There are 23 others standing at this election, many on a narrower range of issues, and some deeply radical in what they want to achieve.)

Allocating funds takes priority over making change

The economy is one area which takes top billing in several manifestos, and you'll find similar priorities: jobs for young people, re-skilling for those who lose jobs and have to find a new one, tax breaks for shops and capital spending to improve transport and broadband. Everyone talks about transition to more renewable energy.

All of these could help improve productivity - a persistent, deep-seated problem, but it's tackled in manifestos in terms of where to allocate marginal amounts of money. Perhaps it needs something more profound about the way business operates and invests, how managers manage and motivate workers, and what, if anything, governments can do to influence that.

On the economy, the consensus doesn't stretch to Scottish Greens. They're outliers among the five main parties, with more of a challenge to the way the economy works. The others vary, but they all go with the grain of the way business operates. They want extra help, at the margins, for small businesses, co-operatives and women entrepreneurs. But the role of big business doesn't get much attention.

SCOTLAND'S ELECTION: THE BASICS

What's happening? On 6 May, people across Scotland will vote to elect 129 Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs). The party that wins the most seats will form the government. Find out more here.

What powers do they have? MSPs pass laws on aspects of life in Scotland such as health, education and transport - and have some powers over tax and welfare benefits.

Climate change requires harder choices and sacrifice by the public.

There's a consensus about climate change and the need to address it. The positive messages are about jobs from renewable power, and the importance of the COP26 summit.

But there are hard messages also. There are implications if Scotland, the UK and other countries are to get to net zero in the next three decades. Sacrifice is required, with change and cost. And it's up to politicians to decide how those sacrifices are distributed.

Oil and gas jobs will go. Car use will be constrained and road space cut back. Air travel will surely continue, but at a higher polluter-must-pay cost. There will be a shift to more expensive electric vehicles.

Nothing hits home in Scotland more than how your home is heated. Expect an enforced shift away from gas heating, requiring new homes not to include it from 2025, and then phasing out of new gas boilers.

The manifestos tell us about plans to improve energy efficiency in homes. With almost every brick cavity now filled, the challenge is to retrofit older stone-built homes. That could be very expensive, disruptive and unpopular.

Scottish Greens go further and faster than others on this. They're talking about, possibly, whole streets being required to retrofit together. That probably means taking old buildings and cladding them internally. And if you haven't reached a minimum level of energy efficiency in your home within five years, Greens would bar you from selling it.

So an election can engage people with difficult issues as well as easy giveaways, and on climate change, we're seeing some of that.

Law and order takes a lower priority

The classic modern manifesto, honed by the New Labour electoral machine, has simply communicated memorable commitments on as few as four issues. Each party has to have something to say about the economy with jobs, health, education and crime.

It is assumed that a promise of several thousand more teachers or nurses is more easily understood as a commitment to education than reassurances about the quality of teaching or healthcare.

While all the parties talk about law and order, or public safety, and want to address public concerns about it, its prominence as a campaign issue has been reduced.

That's probably a sign either recent policies have worked, or that public perceptions have come into line with the less worrying reality, or a bit of both.

The problem is this: if an issue ceases to get much attention and is not an area of party dispute, it is harder to get resources allocated to it.

Spending matters a lot more than taxing

Holyrood has significant new powers to change income tax. It diverged in 2018, with a break from the thresholds and rates set at Westminster.

But there's little difference in what to do with those powers next. The Conservatives have been critical of the SNP's choices as they affect above average earners, and Tories say they would like to re-align with Westminster. But their priority is to spend, not to cut tax.

That has dominated Scottish Parliament thinking since 1999, and the addition of new tax powers hasn't changed much. With so much uncertainty about future tax revenue and block grants, the manifestos offer, at best, a very sketchy picture of how budgets can be balanced. Scottish Labour has a long and expensive wish list, but it's particularly vague on how to pay for them.

MSPs also been able to reform council tax and business rates for 22 years. Neither is seen as fit for purpose in the modern era.

There's widespread support for change, but if you want a worked-out, detailed plan, you won't find one in this election campaign. Conservatives have parked council tax reform, and look to Downing Street to lead on business rates reform. Others at Holyrood hold out, vaguely, for cross-party agreement.

It is now 30 years since the only valuation of property ever carried out for council tax, at the time it was introduced. That is indefensible, but no party is offering to update that.

What difference can Holyrood make anyway?

The answer to that depends on your attitude to independence. There's a lot that can be done at Holyrood, and done differently. Reforming business rates, for instance. And a lot of economic levers at Westminster shape the economy in Scotland. You emphasise what can be done, and what can't, according to political taste.

At this election, government borrowing, to pay for furlough and colossal crisis support for business, is a hugely significant feature of getting the UK and Scottish economies through the crisis.

Holyrood can allocate funds, but doesn't determine the scale of them or when they're withdrawn. That's for Downing Street.

But be careful of the idea that the levers of economic power, spending and tax can be pulled by one government or another, and things happen. It's not that simple.

There's so much more that cannot be controlled; the impact of global economic forces, business investment decisions, consumer sentiment, social change, and new, disruptive technologies.

Government, whether Holyrood or Westminster, can only hope to steer a course through economic waters that can sometimes be very turbulent. Now is one of those times.

POLICIES: Who should I vote for?

CANDIDATES: Who can I vote for in my area?

PODLITICAL: Updates from the campaign

Related topics

- Published15 April 2021

- Published19 April 2021

- Published22 April 2021

- Published14 April 2021

- Published16 April 2021