Empty gallery gives space to restore monumental painting

- Published

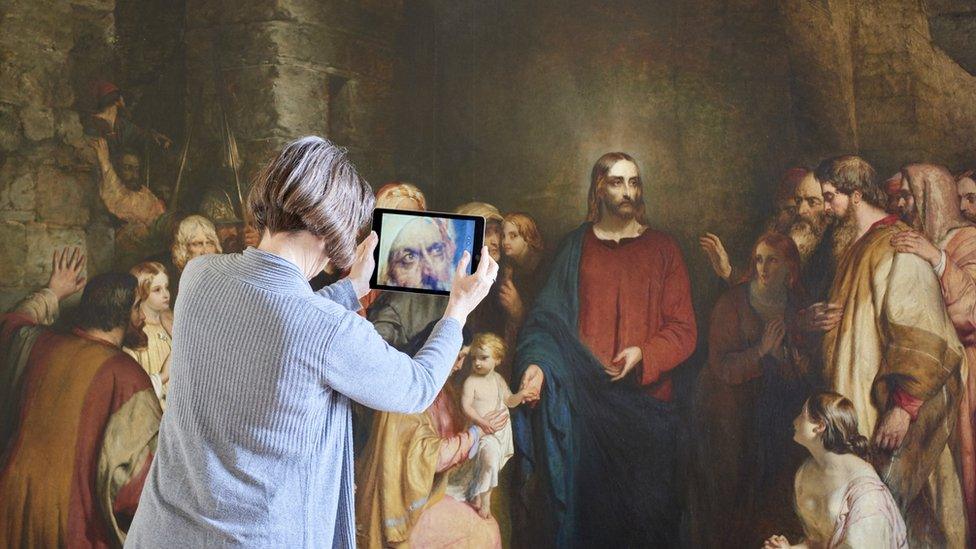

Christ Teacheth Humility by Robert Scott Lauder has been undergoing conservation

A monumental painting by Edinburgh-born artist Robert Scott Lauder is the focus of a major conservation project in an empty gallery space in the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA).

The grand building, built by William Henry Playfair, has stood in the centre of Edinburgh for almost 200 years, housing many exhibitions over the years on subjects ranging from Scottish antiquaries to Andy Warhol.

But, at the moment, there is only one painting in it and one person at work.

Lesley Stevenson, senior paintings conservator at the National Galleries of Scotland, has been working here on and off over both Covid lockdowns.

Lesley Stevenson said she needed space to carry out the work

She has been concentrating on just one painting - Christ Teacheth Humility.

As well as being one of the first works acquired by the National Galleries of Scotland, the painting is also one of the largest.

At 3m wide and 2m high (10ft by 7ft), this biblical scene was too large to fit into the conservation studio in normal times. Then the pandemic hit, and galleries and museums had to close their doors.

"I needed a space and by chance the galleries at RSA were empty so we were able to negotiate a space to work in peace and relative isolation," Ms Stevenson said.

"These galleries are usually busy with people visiting exhibitions, the noise from Princes Street and security staff coming in and out so it has been very strange."

It also marks the end of a strange and complicated journey for the work, which was completed by the artist in 1847 for a competition for the Houses of Parliament, which was being rebuilt at Westminster.

A devastating fire destroyed both Houses of Parliament in 1834 and the competitions were designed to encourage the production of large-scale narrative paintings to furnish the new building.

Lauder, as one of the most feted portrait painters of the day, saw it as the opportunity of his career.

The work he made was exhibited in Westminster Hall but despite widespread admiration didn't win the competition.

Detail from the painting

Instead it was bought for £400 by the Borough Treasurer of Salford, and shown in Sheffield before being sold to the Royal Association for the Promotion of the Fine Arts in Scotland for £200 (it was all they had to offer).

Their hope was that the painting would be the foundation piece of a Scottish National Gallery.

Lauder was equally delighted and rejoiced "that a work upon which he has put forth his whole strength, has found a lasting resting place in his native city".

Strangely, the work was first exhibited in the exact same space it sits in now, in what was by then the Royal Institution of Art.

It had some conservation work then too - back in the artist's studio where he added even more detail to the already elaborate scene.

"It had been on display next to heated flues, which I take to mean some sort of chimney, " says Ms Stevenson.

"It was returned for 'restoration' but when the frame was taken off and he saw large areas in the top corners he clearly thought, 'you know what, I didn't win the competition but I can expand and improve on it'."

A discoloured swab as the conservation takes place

There's a nod to Scotland too in the addition of a very Scottish-looking tower.

The painting's size and scale has made it difficult to keep on long-term display in Edinburgh and for a number of years it was on loan to Leuchie House, a respite care centre in East Lothian.

But it is regarded as a key work in the history of Scottish art, and this very gallery.

It will be centre stage in the new Gallery of Scottish Art, which is due to open in the new space beneath The Mound in late 2022.

For Ms Stevenson, it's been an important turning point for the painting, which will not just allow it to be seen in public again, but will allow visitors to understand how the artist worked to create this epic work.

"Whenever we embark on a project like this, a huge part is about the investigation of how the painting was made," she says.

"Evolution, how the painting began, the layers of paint and what was happening to it in the intervening years.

"I've been so privileged to have this space. I have a few weeks left to work and then I'll be sad to leave but all the work we do is to make the paintings accessible, get them out there, get more people to see them.

"I'll be really delighted when the new galleries open and the painting will be reunited with its restored frame. That will be the best moment, really."