Monk admits abuse after victim's fight for justice

- Published

Fr Denis "Chrysostom" Alexander arrived at court in a wheelchair

A former monk at a Catholic boarding school has pleaded guilty to child sexual abuse, bringing to an end one victim's eight-year fight for justice.

Fr Denis "Chrysostom" Alexander, who is now 85, admitted two charges of lewd, indecent and libidinous practices against two boys between 1973 and 1976.

The offences took place at the Fort Augustus Abbey school in the Highlands.

Alexander, an Australian national, was first named as a paedophile by a BBC Scotland documentary in 2013.

One of his victims was Hugh Kennedy, now aged 58. He was in court and afterwards said his nightmare was "now finally over."

Alexander has been in custody in Australia and then Scotland since 2017. He will be sentenced next month.

The allegations relate to the former Fort Augustus Abbey Roman Catholic boarding school

Fort Augustus Abbey, at the southern end of Loch Ness, had been monastery for more than 100 years. The austere Benedictine monks who lived there operated a prestigious fee-paying Catholic boarding school, thought of as one of the best in the country.

The imposing abbey and school buildings were neatly tucked away behind the trees on the outskirts of the town.

The monks were rarely seen by locals, and were thought of as an amusing peculiarity. At its peak, about 300 pupils would board at the school.

Hugh Kennedy enrolled in 1974; a wide-eyed, blonde-haired boy of 11 who loved sport.

He was exactly the type of boy expected to excel within this environment.

But the strict and regularly brutal regime at Fort Augustus, alongside a hierarchical culture of bullying by his peers, would soon have him living in fear.

One teacher in particular had started to single him out for special punishment.

Fr Denis Alexander, also known as Fr Chrysostom, was an Australian priest who had arrived at Fort Augustus in the 1950s, around the same time as his fellow Australians, Frs Aidan and Fabian Duggan.

Fr Aidan Duggan was another Australian priest at the school

Each of this trio could be sadistically violent and would be eventually be exposed by the BBC as child sex abusers.

Hugh Kennedy says Alexander would call him to his room, where he would be told to take his pants down and he would cane his bare backside.

"He was softening me up, I now understand," Hugh says.

"I used to ask him why he was doing this but he just told me to shut up.

"I was receiving inexplicable beatings. He once made me kneel against the wall for six hours - he was terrorising me.

"Then suddenly it turned around on a sixpence. The beatings stopped; I was put back on his social list, which meant special treats like toast in his office, and yoga lessons. I was even made head altar boy.

"But this was all part of the grooming process, just to get me used to saying yes to everything."

Hugh Kennedy attended the school in 1970s

Soon after, the sexual abuse started.

One night, in the dormitory Hugh shared with more than a dozen other boys, he awoke with a start to the smell of whisky close to his face. Alexander had crept into Hugh's dorm and abused him on his top bunk while the boy below him slept.

"By the next day, I'd convinced myself it hadn't happened," Hugh says.

But the abuse escalated, and during a yoga class, Alexander carried out a serious sexual attack on Hugh.

"He told me it was a special thing between the two of us and no-one needed to know about it, and that no-one would believe me in any case," Hugh says.

The abuse by Alexander stopped, but later he was abused by another man at the school - an art teacher called Bill Owen, who is now dead - fuelling fears that abusive staff had shared victims.

Hugh says the abuse by Owen was serious and lasted several years.

"I believe it was organised, that there was a bit of 'pass the parcel' going on," Hugh says.

Hugh decided to tell someone about the abuse by Alexander.

He told his step-mother and the headmaster at the time, Fr Francis Davidson.

However, Davidson took Alexander's side and allowed the monk to visit Hugh's step-mother at home, to persuade her that her son was lying.

It worked, and Hugh was returned to the school. The police were never called.

Fr Chrysostom was known as the "piping monk" because of his love of the bagpipes

Fr Chrysostom, who was known as the "piping monk" because of his love of the bagpipes, was free to carry on abusing.

And he did.

Nearly a decade ago, alongside producer Murdoch Rodgers, I started investigating allegations of abuse at Fort Augustus.

We met former Fort Augustus pupil Brendan, not his real name, who told us he had been repeatedly abused by Alexander when aged 13.

He had struggled with his mental health throughout his life, a condition rooted in, he believes, the abuse he suffered at the hands of the monk he knew as Fr Chrysostom

It was Brendan's story which started us on our path of investigating Alexander, who we knew had abruptly returned to his native Australia in 1977.

Brendan had raised the alarm about Alexander's abuse, and his parents complained to the school. The matter was once more dealt with internally by Fr Francis Davidson. There would be no police involvement, but this time Alexander was sent home to Australia.

Father Francis Davidson dealt with complaints against Alexander

I had wanted to find and confront Alexander in Australia but needed more evidence.

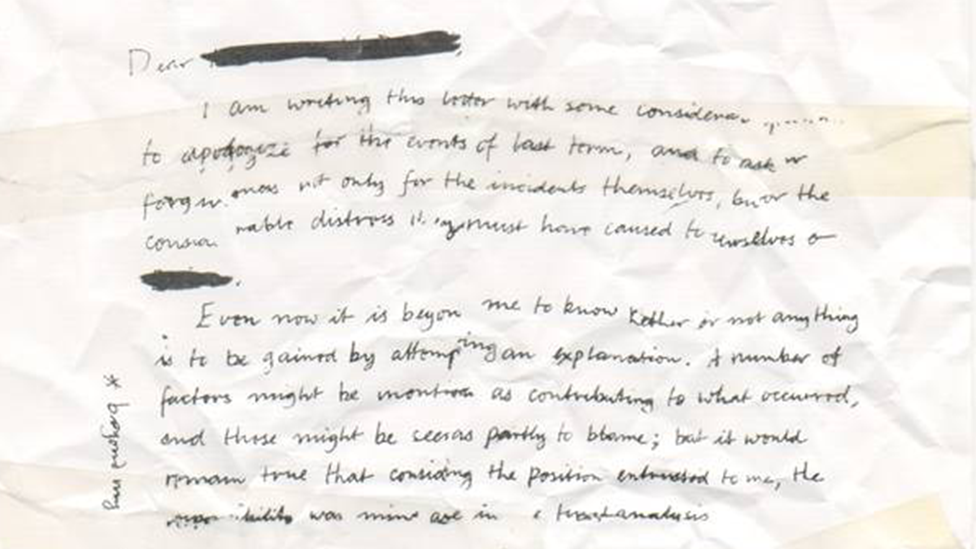

Then Brendan told us about a letter he'd been written by Alexander. It had been an apology - a confession - written to him and his parents on his return to Australia.

Brendan told us he'd been so angry he'd ripped it into pieces and threw it in the bin. Crucial evidence, apparently destroyed 35 years previously in the heat of the moment

But unknown to Brendan, his father had taped it back together and kept it.

Brendan's father taped the letter back together after he ripped it up

The letter reads: "I am writing this letter with some consideration to apologise for the events of last term. I ask forgiveness not only for the incidents themselves but for the considerable distress it must have caused…

"All I can say is that I was under severe strain for the past 18 months…"

Back to Australia

It was all the evidence I needed. I tracked Alexander down to a quiet suburb of Sydney.

He'd been allowed to take up the priesthood in Australia without any prior warnings about his offending being given by the Benedictines.

In fact, he'd been sent a cheque for £50,000 in 2000 by the Benedictines, after the Fort Augustus Abbey had been closed and its affairs wound up. This was despite his confession about abusing children.

Unfettered by allegations about his past, he worked as a supply priest in Sydney for more than 20 years, attending holy communions and baptisms up until his retirement in the 2000s.

Cameraman Alan Harcus and I watched his home for eight days, waiting for the opportunity to put Brendan's allegations to him. Finally, just hours before we were due to fly home, he emerged from his front door.

The former monk refused to engage with my questions, told me to "go to blazes" and get off his property, then rammed his car into mine.

He'd been defiant, but this was a watershed moment in the investigation. The clock was now running.

Father Chrysostom Alexander is accused of abuse while teaching at a Catholic school

The confrontation featured our 2013 documentary Sins of Our Fathers, which sparked a chain of events which ultimately would lead to the setting up of the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry and a major police investigation into Alexander and others.

The programme and subsequent follow-ups named more than a dozen Fort Augustus monks as abusers and several headmasters, including Fr Davidson, of covering up the abuse. Davidson, who is now dead, resigned from a religious post at Oxford university in the wake of the scandal.

Face the consequences

In 2013, Hugh Kennedy had just gone to the police about his abuse, and after watching the film, decided to speak publicly.

Hugh had struggled with his mental health throughout his life and believes his experiences at Fort Augustus contributed to a breakdown of his marriage and put pressure on other relationships.

He told me then that he wanted to apologise to his family "for what I put them through".

He said that Alexander had to face the consequences for his actions, saying, "I will face Chrysostom if needs be… because this is a bogeyman that's been on my shoulder my whole life."

Today, he says that had he known what the experience of going through the criminal justice system would be for a survivor of child sexual abuse, he would never have come forward.

"It has been eight years of pain," Hugh said.

The timeline of the case

July 2013: BBC airs Sins of Our Fathers, revealing decades of sexual and physical abuse at the Fort Augustus Abbey School and Carlkemp preparatory school, and confronts Fr Alexander in Sydney

December 2015: The Crown announces plans to extradite Fr Alexander back to Scotland

January 2017: Fr Alexander is arrested in Sydney and remanded in custody

May 2017: Fr Alexander is found eligible for extradition by an Australian court. He appeals, claiming he is too ill to travel

March 2019: The attorney general of Australia determines that Fr Alexander be surrendered to the UK. Fr Alexander seeks a judicial review.

September 2019: The Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry takes evidence about Fort Augustus

November 2019: The Federal Court of Australia dismisses Fr Alexander's application for a judicial review

December 2019: Fr Alexander fails to lodge an appeal against the federal court ruling within the 28-day deadline

January 2020: Fr Alexander is extradited to Scotland

June 2021: Fr Alexander pleads guilty to two charges

What followed for Hugh Kennedy was a rollercoaster eight years of not knowing whether his abuser would ever face justice.

It was more than two years before the Crown Office sought Alexander's extradition from Australia, then another two years before he was arrested. In the meantime, the BBC continued to report on Hugh's case and ask questions about the delays.

Alexander had claimed he was too ill to be extradited and lodged several appeals. He had told the BBC before his arrest that he was being supported by the Catholic Church in Sydney, although this was denied by the church.

Eventually, having expended all legal means of defiance, he was flown to Scotland in January last year.

"I was told the matter would be dealt with swiftly and expected a trial within a few months," said Hugh.

Hugh Kennedy said the journey to this day was horrific

But then the pandemic struck, and justice ground to halt. Even once trials resumed, Hugh felt the case had been put on the back burner.

"It was almost as if it would have been easier for them if he just passed away in his cell.

"To survive the abuse is one thing, but to survive going through the criminal justice system is another thing altogether. The journey is horrific.

"I was continually kept in the dark.

"There's so much that could have been done differently. There seems to be no insight into the mental trauma involved for victims.

"Initially I put my trust in these people, but then found myself being let down continually. There's a lack of compassion, you're treated dismissively and there seems to be total lack training for staff dealing with these sorts of situations

"I would have crumbled if it wasn't for the support I was getting. I've got a fairly strong constitution but I've not been particularly well during this process, and people with lesser capacity would have sunk and gone away.

"If the BBC hadn't been continually covering this case, I doubt I had the ability to get it this far. What about all the other people who haven't journalists keeping the story in the public eye? They've got no chance of getting a case like this to court.

"Something has to change to make it easier for people to go through this process."

'It's finally over'

Denis Alexander has never given a full public account of his time at the Fort Augustus Abbey school

Until three days ago, Hugh had been living in fear that the case would be abandoned because of Alexander's failing health, or that he would die before going to trial.

On Wednesday morning, he was told of Alexander's intention to plead guilty.

In a voice racked with emotion, Hugh had struggled to get the words out when he called.

"All I've ever wanted was for him to admit what he's done to me and the others," he said.

"It's finally over."

He travelled up from the south of England overnight to see his "bogeyman" one final time.

Dressed in a green prison jumper, Alexander listened to the court proceedings in his wheelchair.

His defence counsel said the man sitting in court was very different to the one who carried out the offences.

Hugh says he is now ready to get on with his life. The ghosts of Fort Augustus are fading, and despite the struggle, he knows he has achieved something that for years had hung in the balance. He'd survived, and he'd won justice.

He said: "There are others who didn't feel able to go through with this. So even if it has been a living nightmare for eight years, I feel I did something right, for Brendan, for me, and for the others who didn't make it this far."

Related topics

- Published21 December 2017

- Published23 January 2017

- Published20 December 2019

- Published15 August 2013

- Published29 July 2013