Euro 2020: The ways Scotland has changed since France '98

- Published

Eight-year-old CJ with Moroccan fans during the 1998 World Cup in France

When Scotland's men last played in a major football tournament, C'est La Vie by B*witched was at number one in the charts, there was no Scottish Parliament and Google didn't exist.

It was the summer of 1998 and eight-year-old CJ Cook was among the fans in France for the World Cup.

Now 31 and a civil servant, she remembers "an amazing party" with a samba band soundtrack - "an overwhelming experience" for a child.

"The carnival atmosphere of France was very different to lower league Scottish football on a Saturday afternoon in the rain," CJ told BBC Scotland's The Nine.

The national team were full of pride, passion and promise but failed to make it out of the initial group stages after a typical combination of blunders and bad luck - including an agonising own goal against Brazil in the competition's opening game in Paris.

CJ says supporting Scotland has been "tiring" over the past two decades

It was the start of a 23-year-long drought which CJ describes as "tiring", even though she was - and remains - a loyal member of the Tartan Army, as Scotland's travelling support is known.

"We have snatched defeat from the jaws of victory on many an occasion," says CJ, wearily.

If 1998 was the beginning of one gap in Scotland's national story, it was the end of another: the last full year without a parliament in Edinburgh for nearly three centuries.

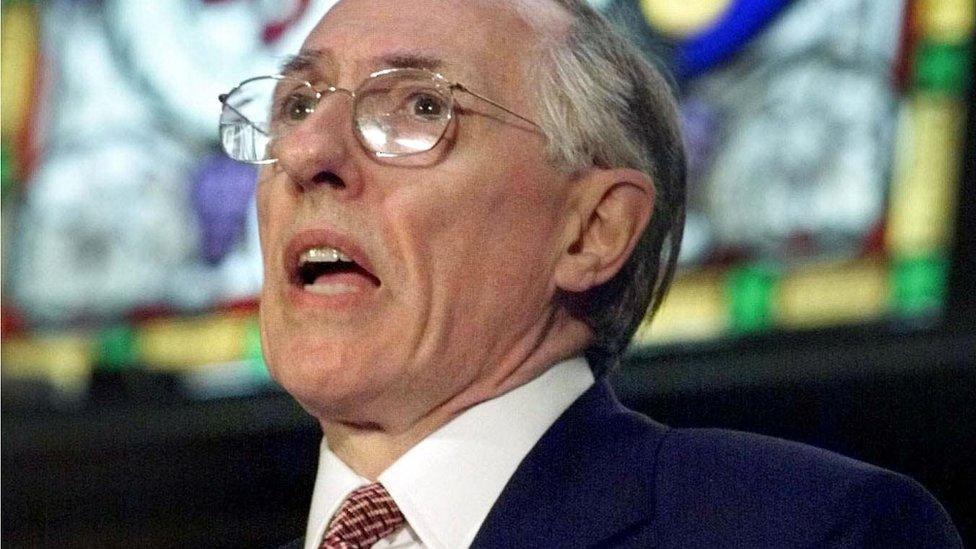

"Today there is a new voice in the land," proclaimed Scotland's first First Minister, Donald Dewar as the new parliament opened in temporary accommodation on The Mound 10 months after that World Cup in France.

It was, said Dewar, "the voice of a democratic parliament. A voice to shape Scotland. A voice, above all, for the future."

Donald Dewar opening the first Scottish Parliament in 300 years in 1999

Writer and broadcaster Stuart Cosgrove suggests the advent of devolution may have had an effect on Scottish football, taking some of the heat out of the game.

While football was once "the big volcano of patriotic fervour," Cosgrove argues that there are now many more options to display "Scottishness" - through the parliament itself; in what he calls the civic nationalist movement; and, increasingly, by following other national team sports.

"I wonder if it is the case now that Scotland has so many different places that it can celebrate its cultural and national identity that actually maybe it doesn't need football as much as it once did?" Cosgrove says.

Ahead of Euro 2020, Scotland fans share their memories of the World Cup in 1998

Certainly the environment in which the game is played has changed dramatically.

Scottish football was forged in fire and dust, the fixation of a nation powered by heavy industry.

Glasgow's Hampden Park has been the scene of many great football battles

To the cities and towns of toil the sport offered not just tribal pride but glimpses of grace and glory.

When 149,415 souls sardined into Glasgow's Hampden Park to see Scotland beat England 3-1 in 1937, the roar of the crowd had its echoes in the thunder of the furnace, the clanking of the shipyard and the rattle of the pit.

Football then was a game for men - men of coal and steel and iron. But those days are long gone, that Scotland is no more, and football has changed too.

"With the decline of industry comes a kind of haemorrhaging," says Cosgrove.

"Social housing had been the heartbeat of football," he says, and its decline largely killed off "the kickabout" in back courts and cobbled streets.

Football is no longer such a common sight on Glasgow's streets

As Scotland become wealthier, healthier and more aspirational, car and home ownership rose and the space for street football - literally and imaginatively - was squeezed.

Plus we now had other things to do: competition for young minds and young feet.

Kevin's 11-year-old daughter plays up front for the under-13s team which he coaches in Perth.

"Emmy loves her football," he says.

"But I still have to drag her off her Xbox to come along to training."

Emmy chases the ball during a game in Perth

We meet Kevin and Emmy on a busy playing field in Perth on a sunny Saturday morning. This is the home of Jeanfield Swifts, and half a dozen games and training sessions are already under way.

"I've always played football in school but nobody would ever pass to me because I was the only girl playing," says Emmy.

"I had to gain their respect and now they pass to me."

Was that annoying?

"Yeah," says Emmy, "I had to tackle my own team mates."

Her dad says the arrival of more families at league football games has created a space for girls' and women's football to flourish and has forced men to improve their behaviour.

Kevin says men have had to improve their behaviour

"Some of the songs they sang back in the days, you wouldn't do it when your mum's there or your daughter's there or your wife's there," he admits. "There's not a chance."

Kevin says there is still a class divide at games between what he jokingly refers to as the "prawn sandwich brigade" and the "ruffians" - but overall those distinctions are melting away, he reckons.

"Football was designed for the working class," he says.

"Saturday morning you do your shift, you finish, you get a quick drink with your friends and then you're off to your local team," Kevin says.

"That's not a thing anymore. Football's had to change its outlook and try to encourage families."

Thousands of Rangers fans marched to George Square after the team won the Scottish league

Of course there are still plenty of working men for whom a couple of pints and a game of football is woven into the weekend as an enjoyable ritual, and some of the darker aspects of the game haven't vanished either.

In some quarters the shameful shadow of violence and sectarianism remains, as demonstrated by last month's violent, anti-Irish, anti-Catholic disorder by a minority of Rangers fans celebrating their team's league title in Glasgow's George Square.

But for Mary Docherty, who grew up in Hamilton, South Lanarkshire, but now lives in Kinross, the game and the country have changed "unrecognisably".

Scotland, she argues, is now more confident, with a stronger sense of national identity, than it was at the time of France '98.

Mary Docherty with her daughter Olivia

She also sees an opportunity shift for her sports-mad daughters, including Olivia, 16, who plays for Jeanfield Swifts under-17s and hopes to win a sports scholarship to study soccer in the United States.

Mary says she's "really excited" about where sport could take her daughters, and girls in general.

"There are opportunities now that just didn't exist before," she says.

As for Emmy, who 90 minutes later will be scoring a brace in her team's 8-2 victory - what does she get out of football?

Without hesitation, the 11-year-old replies with a big smile and a single word: "Joy."