What happened to Scotland's 'free from Covid' hopes?

- Published

- comments

With schools closed for summer, families enjoy the sunshine at Coldingham Sands

This time last year, Scotland beginning to open up after the first wave of Covid. There was even optimistic talk of eliminating the virus by the end of summer 2020. But 12 months on, Scotland is seeing some of the highest virus rates of any European country. Can we find that optimism again?

On 13 July 2020, shopping centres in Scotland had reopened; there had been no recorded deaths for a fifth day and new positive cases stood at just 19.

Last summer, small outbreaks were being easily identified and stamped on quickly and optimism rang loud when First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said the elimination of coronavirus was not far away.

It was a sentiment echoed by one of the experts on the government's Covid-19 advisory group, Professor Devi Sridhar, of Edinburgh University, who said the country would effectively be Covid-free by the end of the summer should current progress be maintained.

Her prediction was essentially correct, with a seven-day rate of 15.4 cases per 100,000 people on 1 September 2020.

Ten months on, that rate has shot up to 420.1 - so what's changed?

In a word, variants.

More transmissible strain

Prof Sridhar recalled: "If I think back to last summer, there were reports out of Italy suggesting that, if anything, the virus was going to mutate into a milder form.

"We did think the wild-type - or unmutated - strain was bad enough, but then Alpha came along. That has now been followed by Delta which makes Alpha look easy."

The Delta variant - first identified in India - is known to be significantly more transmissible than earlier strains, and has been seeded in Glasgow - Scotland's biggest and densest urban hub.

And Prof Jason Leitch, Scotland's national clinical director, confirmed the variant was the reason why Scottish health boards featured so prominently in the World Health Organization's chart of European hotspots.

Prof Sridhar explained: "Because of the variants being more transmissible, the percentage of the population that you have to vaccinate - your herd immunity threshold - moves higher.

"The benchmark moved first with Alpha, and now with Delta - these variants keep moving the goalposts."

She also argued that, in some ways, Scotland is a victim of its own success.

Essentially, because fewer people in the country had the virus in the first and second waves, it meant there was no natural - or herd - immunity.

Serology data from the Office of National Statistics shows Scotland has fewer people with antibodies against Covid-19 than south of the border.

But Prof Sridhar said it is not necessarily "a bad thing" that the country did not build a natural immunity.

She added: "We'd rather people get immunity through a vaccine, as studies are showing that vaccine immunity is longer-lasting. You will have a more robust immune response from a vaccine than you do from natural infection."

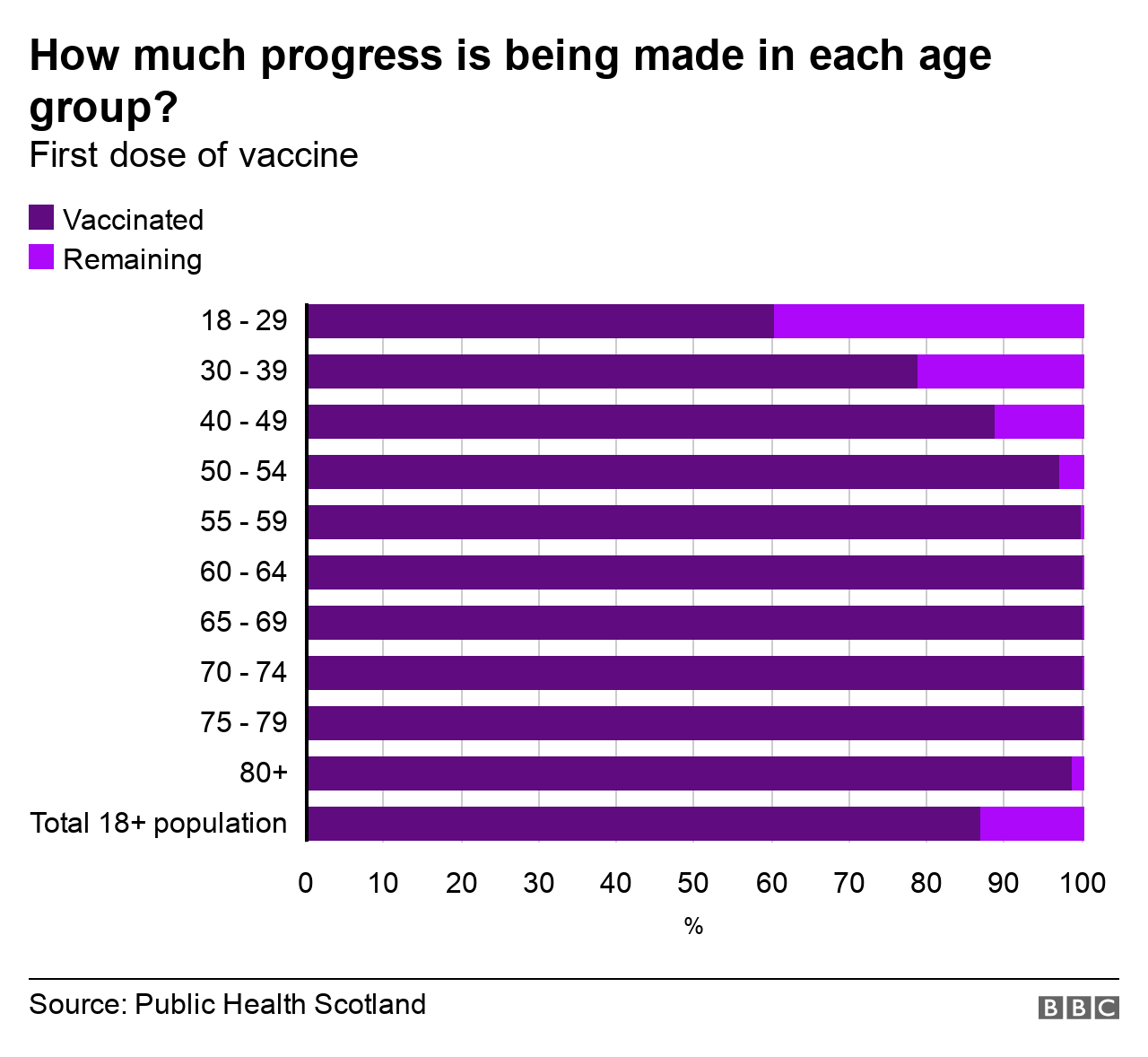

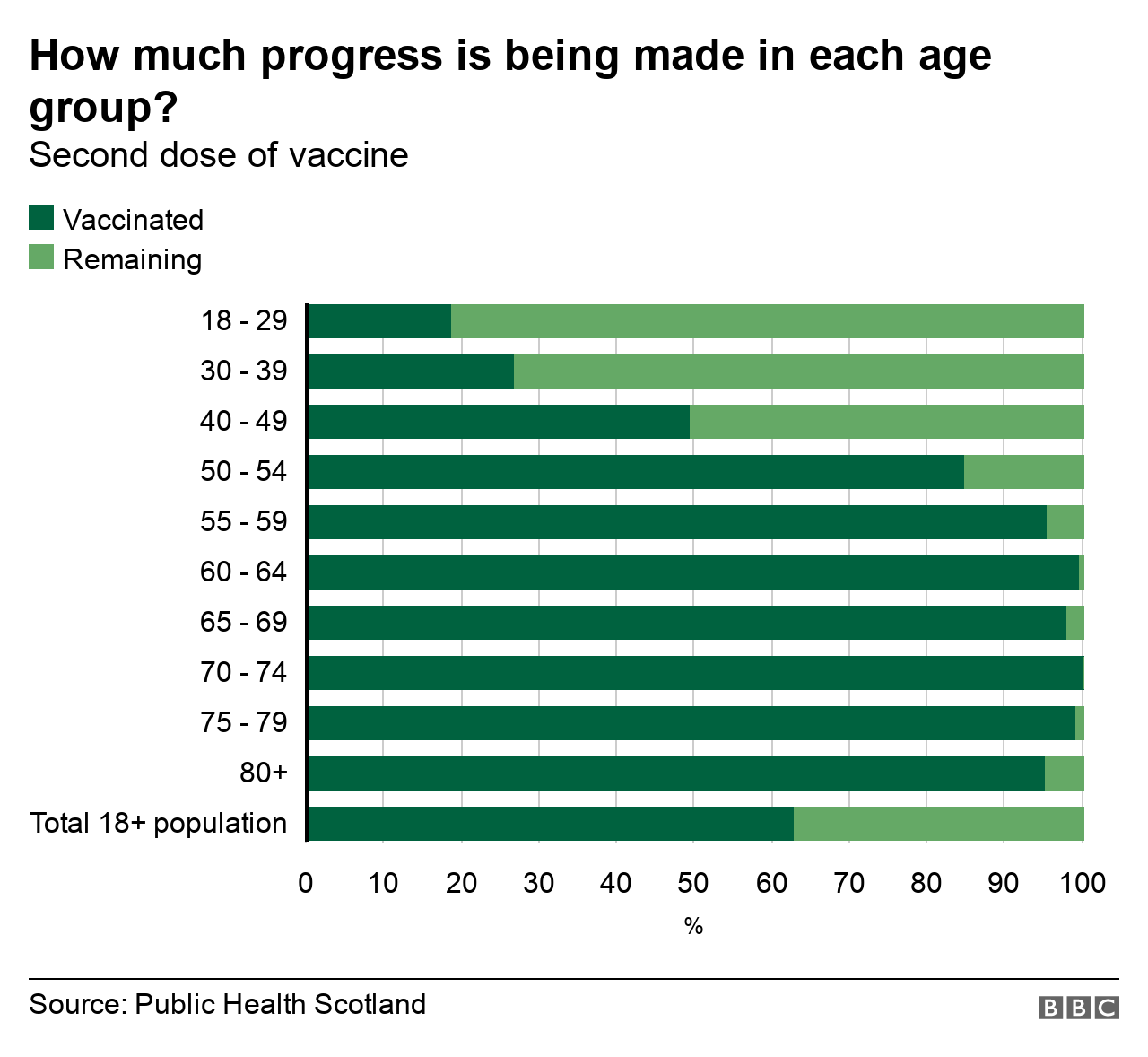

Since the start of the vaccination programme last December, nearly 3.9 million people in Scotland have received their first dose, and 2.7 million their second jab.

A year ago Sir Ian Boyd, who sits on the Sage scientific advisory group and is a professor of biology at St Andrews University, said the chances of getting a vaccine within five years was "moderate".

He acknowledged that the speed with which vaccines had been produced had been "a remarkable achievement, but there has been quite a lot of good luck involved".

Sir Ian said: "It is very difficult to produce vaccines for some viruses but it has emerged that SARS-CoV-2 has some characteristics which mean it stimulates a good immune response."

Why, then, are cases still increasing?

Data from Public Health Scotland shows that, a year ago, women in the 45 to 64 age range accounted for the bulk of the 16 new cases reported on 6 July 2020.

A year on, and the highest case numbers are now in the 20 to 44 age group - 84 women and 60 men.

Essentially a demographic that is least likely to have been double-vaccinated.

Prof Sridhar said this age analysis suggests the vaccination programme is working as fewer people over 50 are getting infected.

The data also suggests that the vaccine may be arresting onward transmission from younger adults to older, vaccinated relatives who may share the same household.

However, both Prof Sridhar and Sir Ian suggest that rather than looking at infections, focus should be shifted to hospitalisation data as a yardstick with which to measure Scotland's progress.

Sir Ian said: "As the older, vulnerable sections of the population have become protected then the unvaccinated, younger section of the population will tend to be those showing the highest prevalence and, in general, they will experience only mild disease.

"We would then expect hospitalisations to remain low compared with last year."

However, as of 30 June, there have been 64 hospitalisations compared to a handful last year.

But Prof Sridhar said many of these were likely only overnight stays compared to multi-day stays that were typical earlier on in the pandemic

She stressed, though, that while there is cause for optimism, there was still a degree of uncertainty because of possible new variants evading "our vaccines".

Vaccine evolution

However, Sir Ian echoed his view of a year ago that people will have to accept a "new normality" in which the virus will never truly go away.

He said: "I expect there will be a continuous process of virus evolution to escape the vaccine and vaccine evolution to catch up with the virus.

"Ongoing vaccination involving boosters and new variations of vaccines will almost certainly be something we need to get used to."

Just as they did 12 months ago, it is expected that restrictions will continue to be lifted in Scotland.

The government's plan is for Scotland to move to level zero on 19 July, with remaining legal restrictions removed from 9 August.

Sir Ian says it is "all about balance of risks" with a calculation being made about whether continuing restrictions will have a greater health impact than Covid infections.

"We are certainly approaching the point where the balance is changing, but this is not a precise science", he said. "[But] it's worth remembering that the virus does not care about government policies, and if lifting restrictions gives it new opportunities then it will exploit those opportunities."

While the last year has shown that coronavirus in all its guises can make a mockery of any predictions, Prof Sridhar pointed to a positive future.

She said: "I think we may have a bumpy winter, but my hope is that by next summer people will look back at these 18 months as a really difficult time in their lives, but one that we've got past."