Highers and Nat 5s: Four things to look out for on results day

- Published

Pupils across Scotland have had confirmation of their grades for their National 5, Higher and Advanced Higher qualifications.

The official texts from the SQA (Scottish Qualifications Authority) gave pupils the results but they won't be a surprise.

Exams were cancelled again this year so their results are based on school assessments and teacher judgements, while the SQA sampled work from different schools for "quality assurance".

This all happened before the end of June so the results won't be new to the young people.

So what do the statistics tell us?

Making the grade?

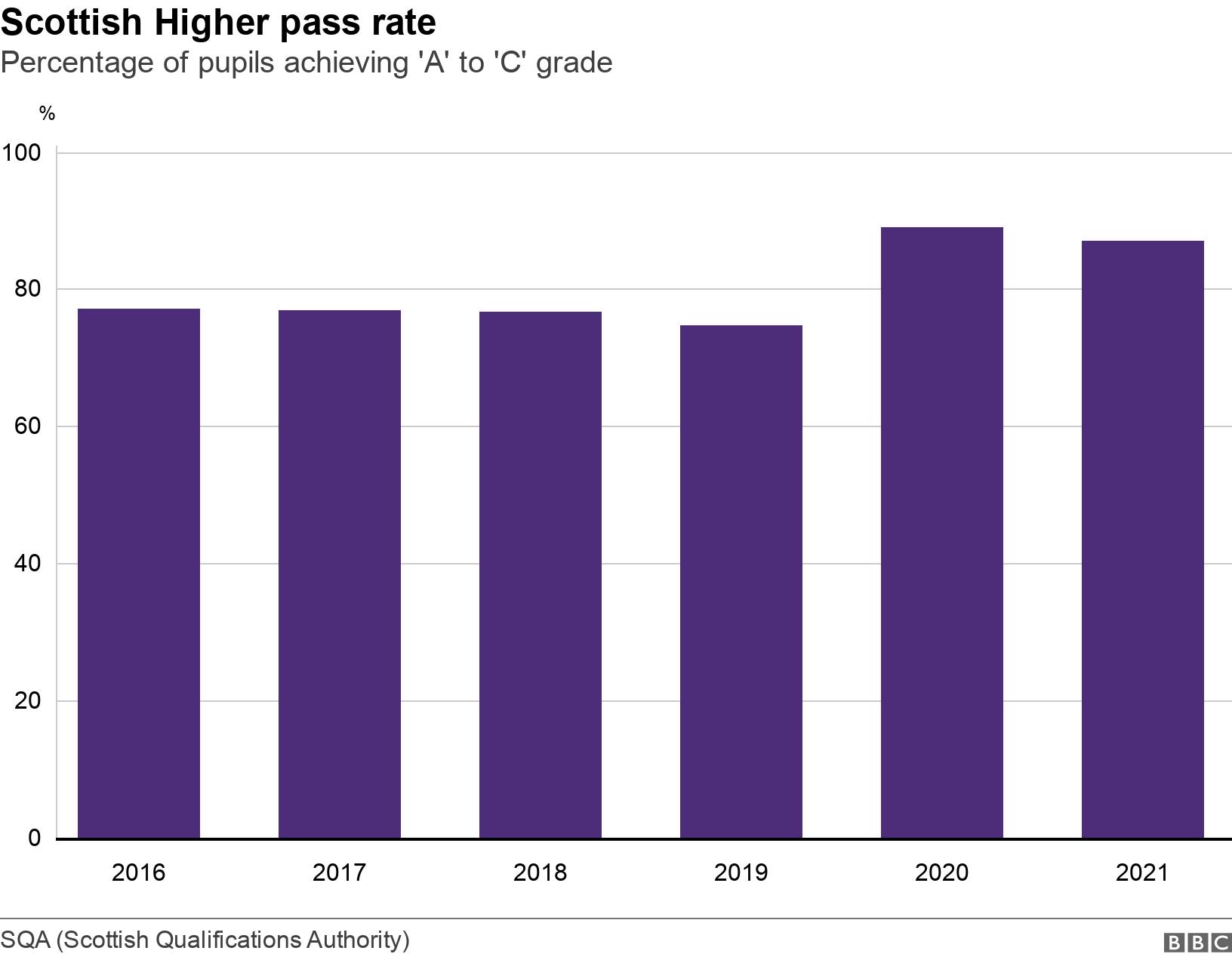

In "normal" years, the pass rate for Higher exams has been sitting between 75% and 78%. In 2020, the first year when there were no exams due to Covid, it was 89%.

This year the rate is 87.3%, down slightly on 2020 but still much higher than usual.

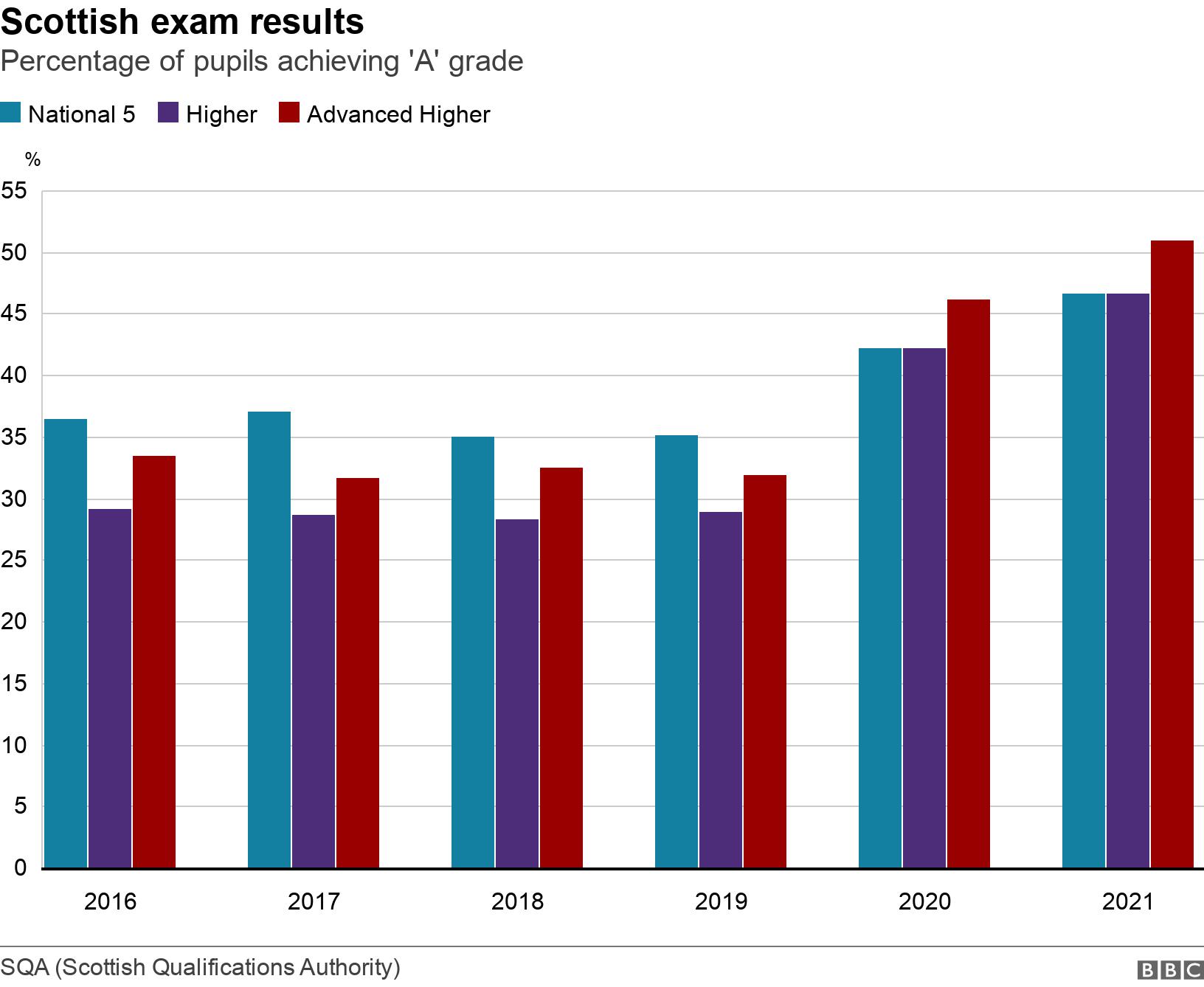

There were also a record number of A grades this year.

A total of 47.6% of Higher candidates achieved an A grade, compared to 40% in 2020 and 28.3% in 2019, when traditional exams were used.

For National 5 the percentage of As went up to 46.7% from 42.3% in 2020.

2020 was a statistical outlier because all results were teacher estimates.

This year, teachers have been involved in coming up with grades but they had to show solid evidence in the form of assessment material, so it's not quite exams, not quite teacher judgement.

Attainment gap

Both the SQA and Scottish government warned against comparing last year's statistics with previous years. 2020 was, as I have already said, an outlier.

2021 is also something of an outlier too.

The SQA said that in the latest results the poverty-related attainment gap was narrower than in 2019, although slightly wider than in 2020.

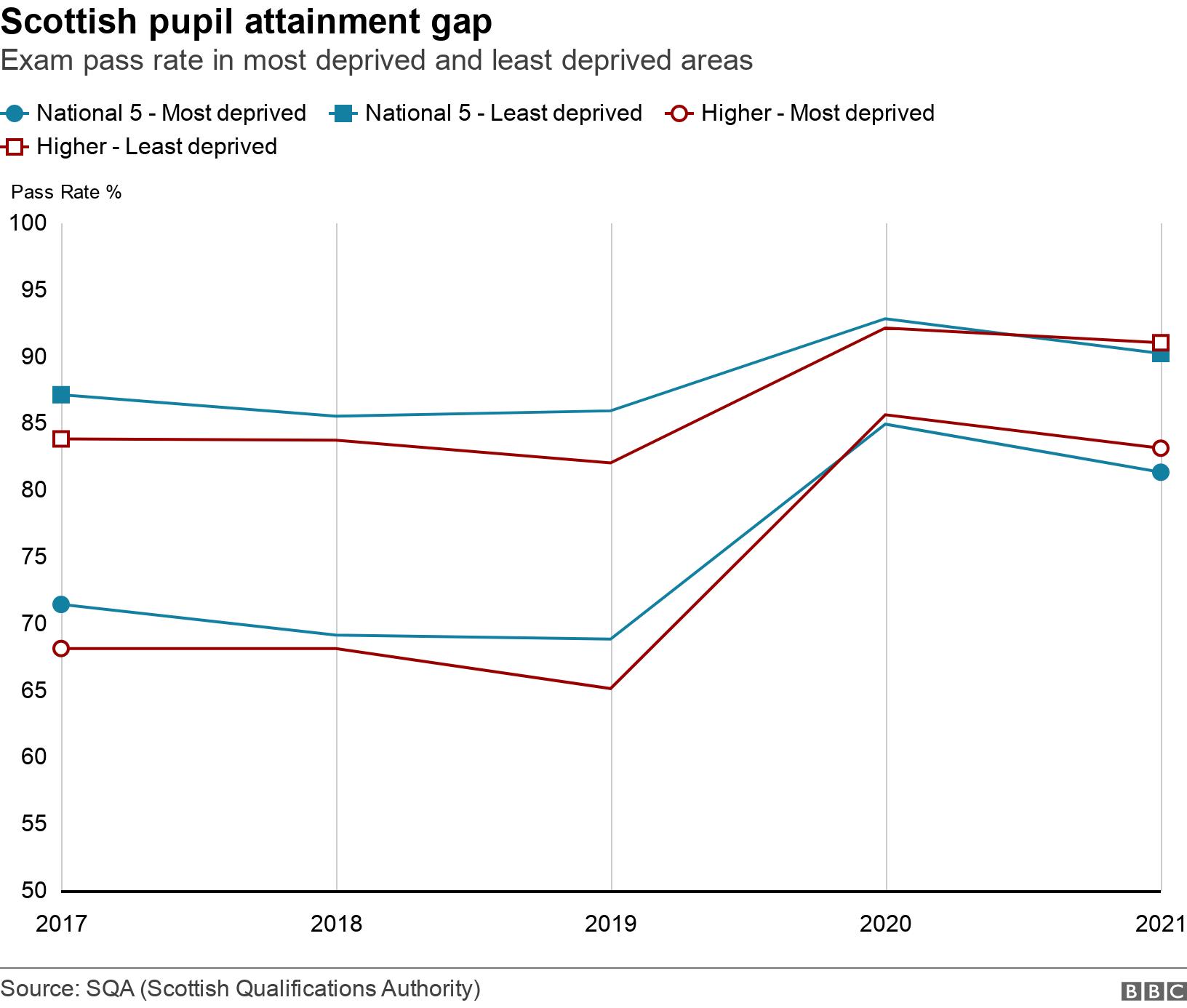

Before the two pandemic years, the gap between the achievements of pupils in the poorest areas and the richest was much larger than it has been for 2020 and 2021.

In 2019 the pass rate at National 5 for the poorest students (the bottom fifth on the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation) was 68.8%. Whereas for those in the wealthiest areas it was 85.9%, a gap of 17 percentage points.

In 2020 pupils were eventually given their teacher estimates as grades and not those moderated to take into account a schools' past performance - the infamous "algorithm", which was scrapped after it was claimed it disadvantaged pupils at schools that had performed poorly in the past.

This closed the attainment gap to 7.9 percentage points.

This year the gap widened to 8.9 percentage points but it is still well below the 2019 figure.

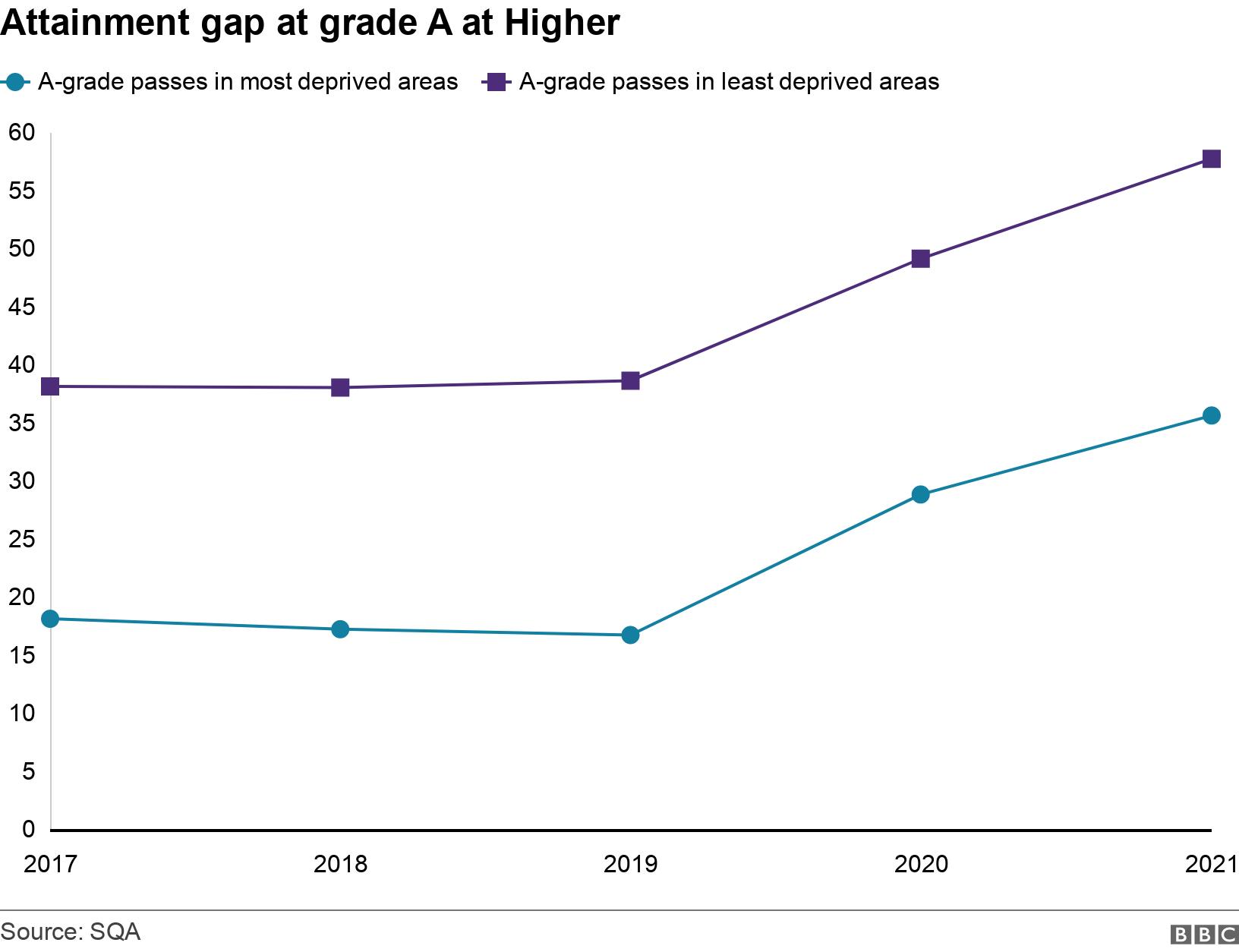

However, while the gap in passes has closed on the pre-pandemic figures. The gap between the number of the most deprived pupils and the least deprived getting an A grade at Higher has remained actually increased.

Despite the number of A passes almost doubling for pupils in the most deprived areas it remains 22% lower than the rate for least deprived.

So while it is likely that those from the least deprived backgrounds have had the most support during online learning, there has been a continued uplift in results in deprived areas too.

Without traditional exams and with teachers able to, in theory, use their judgement, those in the most deprived group could potentially have more of an advantage than they normally do.

We seem to have ended up in a scenario where, on the whole, everyone does better, which is good for the individual, but hasn't closed the attainment gap any further.

How many appeals?

This year, for the first time, pupils can appeal directly to the SQA if they are unhappy with their grade, instead of involving their school. They can appeal for three reasons: against an academic judgement; because of an administrative error; or on the grounds of discrimination.

Pupils have had the ability to lodge their interest in an appeal since they were told their results on a provisional basis and the deadline for this is Thursday.

The number who are planning an appeal is not part of today's statistics.

Numbers are not expected to be particularly high, although there could be a conversation around the choice to not include a right of appeal for exceptional circumstances and the decision to allow marks to be downgraded as well as upgraded, and whether this has put young people off.

Both of these decisions were criticised by the Children and Young People's Commissioner and the Scottish Youth Parliament.

University places

Each year, the Scottish government pays Scottish universities for Scottish students to go there. Usually it puts a cap on the number of places. Last year and this year, the government has increased the cap by about 2,500 places to more than 38,000 places.

It means that even with more pupils than usual meeting the entry requirements for the courses of their choice, they should still get a place on that course.

They may have already been in touch with the university to let them know they have what they need. But institutions could not make anything official until today, when the results are there in black and white.

Those stats show a record number of Scottish-domiciled students being offered a place at Scottish universities.

At the same time there has been a sharp drop in EU students coming study in Scotland as a consequence of Brexit

The Scottish government has committed to extra funding for this year but we are still waiting for confirmation of whether they will do the same for next year's entrants, many of whom will have been sitting Highers this year.

And because of the large numbers of children taking qualifications this year, the number of Higher passes is at a record level.