Edinburgh festivals: No fireworks but many are just happy it happened

- Published

There were no fireworks at the Edinburgh festival this year

In previous years, the nightly fireworks exploding over the Royal Mile have begun to lose their appeal by the end of a long month of Edinburgh's festivals but this August, like so much else, they were missing.

The Edinburgh Military Tattoo itself, which for years has ended each performance in a volley of explosions, was absent from the city. And the international visitors it attracts were nowhere to be seen either.

Even the street performers had restricted hours and spaces as Covid restrictions left their mark.

Even street performers had restricted hours and spaces this year

The Fringe, the International Festival, the book, art and film festivals all went ahead but the Covid limits meant a smaller, more intimate festival experience this year.

Its success will be judged on moments, rather than box office sales.

Most of the festivals had access to public funding, to stage their work in new ways.

The Edinburgh International Festival hired pavilions for their programme of 170 events while four Fringe regulars - the Gilded Balloon, Zoo, Dance Base and the Traverse Theatre - transformed a multi-storey car park into a venue which featured an open-air performance stage, food stalls and bars.

People performed in parks, beaches, back gardens and bandstands but it's not profitable, or sustainable.

With the reduction in social distancing only confirmed a week before the events began, most organisations stuck with two-metre distancing, or sold tickets in family group bubbles.

With tickets limited, and a fraction of the shows on offer, many sold out, giving audiences a rare opportunity to see artists like Damon Albarn or Renee Fleming up close and personal.

The festival did offer a rare chance to see artists such as Damon Albarn with a smaller crowd

Just before his two concerts in Edinburgh, Albarn had performed with his band Gorillaz for 50,000 people at the 02 in London. In Edinburgh, there were just 700 of us.

All five summer festival directors had to plan for the best, but prepare for the worst, and be ready for suddenly cancellations due to Covid.

Book Festival director Nick Barley arrived at Bute House on Sunday, expecting a reception hosted by the first minister, only to be turned around at the front door after Nicola Sturgeon was forced to self-isolate.

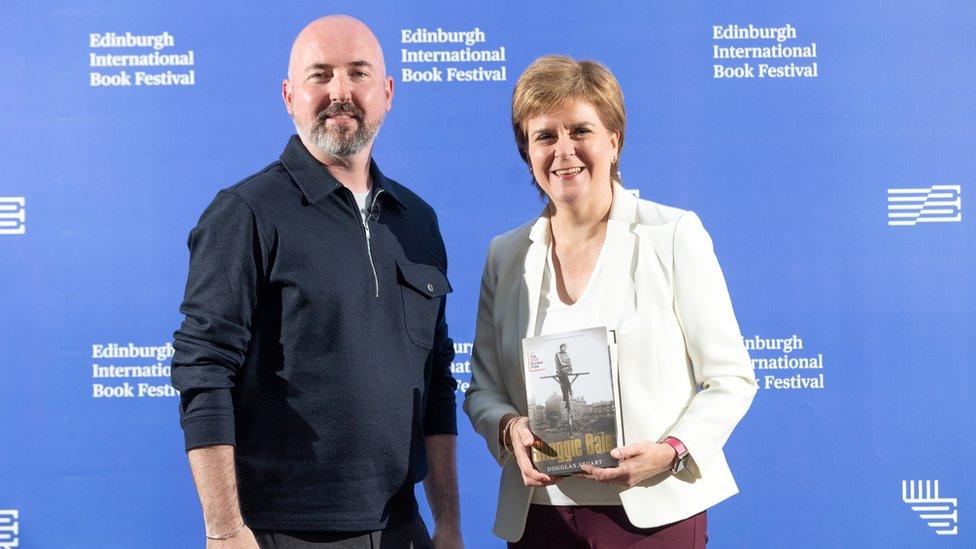

Scottish author Douglas Stuart and First Minister Nicola Sturgeon at the Edinburgh International Book Festival

Plans were already in place for the live event she was due to host with Shuggie Bain author Douglas Stuart on the closing night of the festival, although in the end, both were able to be there in person.

The capacity to be online was vital for all the festivals, and the hybrid approach, with big screens outside, proved to be extremely successful, especially at the book and film festivals.

The Edinburgh International Film Festival was back in the mix this August, having previously relocated to June, and although most of its big name stars were on screen, rather than in person, it added a much-needed buzz to the city.

Ali Whitney, Ritchie Adams, and Hermione Corfield, the stars of The Road Dance, which was the Audience Award at the Edinburgh Film Festival

The pandemic has meant not just a lost year, but a lost title, that of longest continuously running film festival, but it's also revived interest among film fans, not just in Edinburgh but across Scotland, which should stand it in good stead.

Next year marks the 75th anniversary of the Edinburgh International, Fringe and Film festivals.

Many of the things they planned, are already in progress. New ways of working. More collaboration. Sharing resources.

In previous years, the measure of success was at the box office.

An ever-increasing number of tickets sold, or shows staged.

This year, it's been a much quieter success story, and for many, the measure of success is that Edinburgh's festivals happened at all.