What does Boris Johnson's tax rise mean for Scotland and social care?

- Published

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has increased taxes on working people to pay for social care costs

There are similar demographic challenges facing Scotland and England in funding social care, and the responses are increasingly divergent.

Raising National Insurance Contributions feeds a big increase in funding for Holyrood but also breaches an important convention over not "directing" where devolved money is spent.

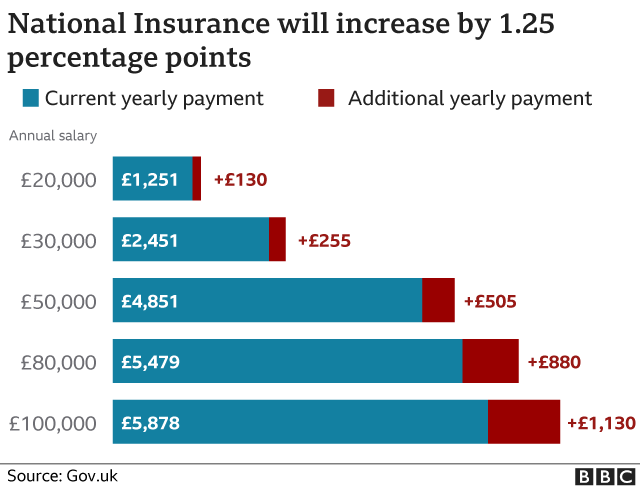

Across the UK from next April, for every extra £1,000 on the typical wage slip, a further £12.50 will be removed before you get it.

The same amount is being levied from employers.

That's true across the UK, because this is a new levy as part of the system of National Insurance Contributions (NIC), a tax which is reserved to Westminster or, if you prefer, not devolved to Scotland.

After the first £9,568 of income, and up to £50,270, every thousand pounds of income is already having £120 deducted from it for NIC.

Yet this is a new tax, called a Health and Social Care Levy, and that's how it will eventually appear on the pay slip.

This is to help repair the damage to the health service from the pandemic. But it's also a permanent commitment to sort out deep-seated problems in social care… in England.

So… What does it mean for Scotland?

The same levy on top of National Insurance Contributions (NIC) will be deducted from Scottish pay slips.

For earnings up to £9,568, there is no contribution, and for every pound after that, there is a 12% deduction, up to £50,270. From that higher threshold, the NIC rate falls to 2%.

Under Boris Johnson's new plans, all rates will go up by 1.25 percentage points.

As well as workers, employers will see their contributions going up from 13.8% of wages by 1.25 percentage points to 15.3%.

In addition to this there will also be a UK-wide additional 1.25% tax on share dividends.

This helps ensure that better-off people who take their income from business earnings rather than salaries and wages will also contribute.

Self-employed workers have a different means of payment, on a flat rate per week, though that is being reviewed by the Treasury.

How will this affect spending in Scotland?

While most of the revenue will go into health and social care in England, part of the £12bn a year to be raised will be allocated to devolved administrations.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said this will rise to £2.2bn in total, of which Holyrood can expect about half.

He added that there is a larger payback through the Barnett spending formula for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland than is paid in NICs. The gap is about £300m.

Uniquely, and with potential for controversy, this is a 'directed' contribution to devolved administrations. Because the money is levied for health and social care, the Treasury will require that it is spent on that.

'Directed' funds breach the convention that block grants are for the devolved administrations to spend as they choose.

It could be seen as a constraint on Holyrood. But Holyrood is free to take other money away from health and social care and spend it on other priorities. MSPs could take the money, maintain spending levels and reduce income tax.

But with political pressure to increase spending, particularly on health and social care, the likely row about being 'directed' to spend money will be about Holyrood being told to do something it wants to do anyway.

The principle is an important one, though, as councils would confirm. Having strings attached to funding limits the ability of governments to flex their budgets.

What is the extra revenue being used for in England?

The number of people requiring care is soaring with no sign of slowing down

This week has seen a very strange way of handling an issue that previously tripped up previous administrations, both Labour and Conservative.

The kite-flying over recent days about the use of NICs to fund extra spending on health and social care drew attention to the funding question rather than what it's actually for.

Tuesday brought confirmation of the use of NICs, and a clearer picture of what Whitehall intends to do with social care.

The answer is a big boost to health spending initially, and then shifting the levy towards social care.

For those requiring residential care, there will be a promise not to require more than £85,000 to be spent over a lifetime.

That should mean many people with savings up to that level will not have to sell their homes to pay for care, and they will be able to leave the value of their home and other assets to their families.

Because of that choice, a great deal of the benefit from this new system goes to homeowners, and particularly to those living in the most valuable homes, who tend to be in the south of England.

Anyone with less than £20,000 in England will have their costs met by the taxpayer, raising that threshold from £13,000.

How does that social care system contrast with Scotland's?

There's quite a wide gulf between the English and Scottish systems. But the pressures on them are similar.

Many more people are living longer, partly because of the demographic bulge from baby boomers and also because of better health and healthcare.

The incidence of dementia is rising steeply as the numbers of the very old increase rapidly. And there are high costs for councils for the often complex care needs of adults under the age of 65.

The demographic pressure in Scotland is more acute, as the working age population is now falling while the number of people in older age is on the rise. England has a higher birth rate and more immigration.

There is pressure for reform of social care in Scotland but it is less intense. The squeeze on social care funding over the past 12 years has been significantly lower in Scotland than south of the border.

The big divergence in approach came in 2002, when the Scottish Parliament introduced 'free personal and nursing care' for those assessed as needing it.

That doesn't mean all care becomes free, and the weekly amount has been squeezed while costs have gone up. This year, it can mean £280 per week for those in need of both personal and nursing care.

Those requiring residential care, and with assets of more than £16,000, are required to pay towards the costs.

Those with lower assets (typically savings) have their care provided by their council, with Scottish government support, at £654 per week for personal care, and £762 weekly for nursing care.

Those with assets of more than £28,000 have to fund much of the cost of staying in residential care, as well as home care requirements. They can get the £280 weekly payment, but have to pay higher rates than councils do by £200 to £300. So they subsidise the state-funded residents.

For those with assets of between £16,000 and £28,000, there is a tapering level of government support.

How is social care in Scotland likely to change?

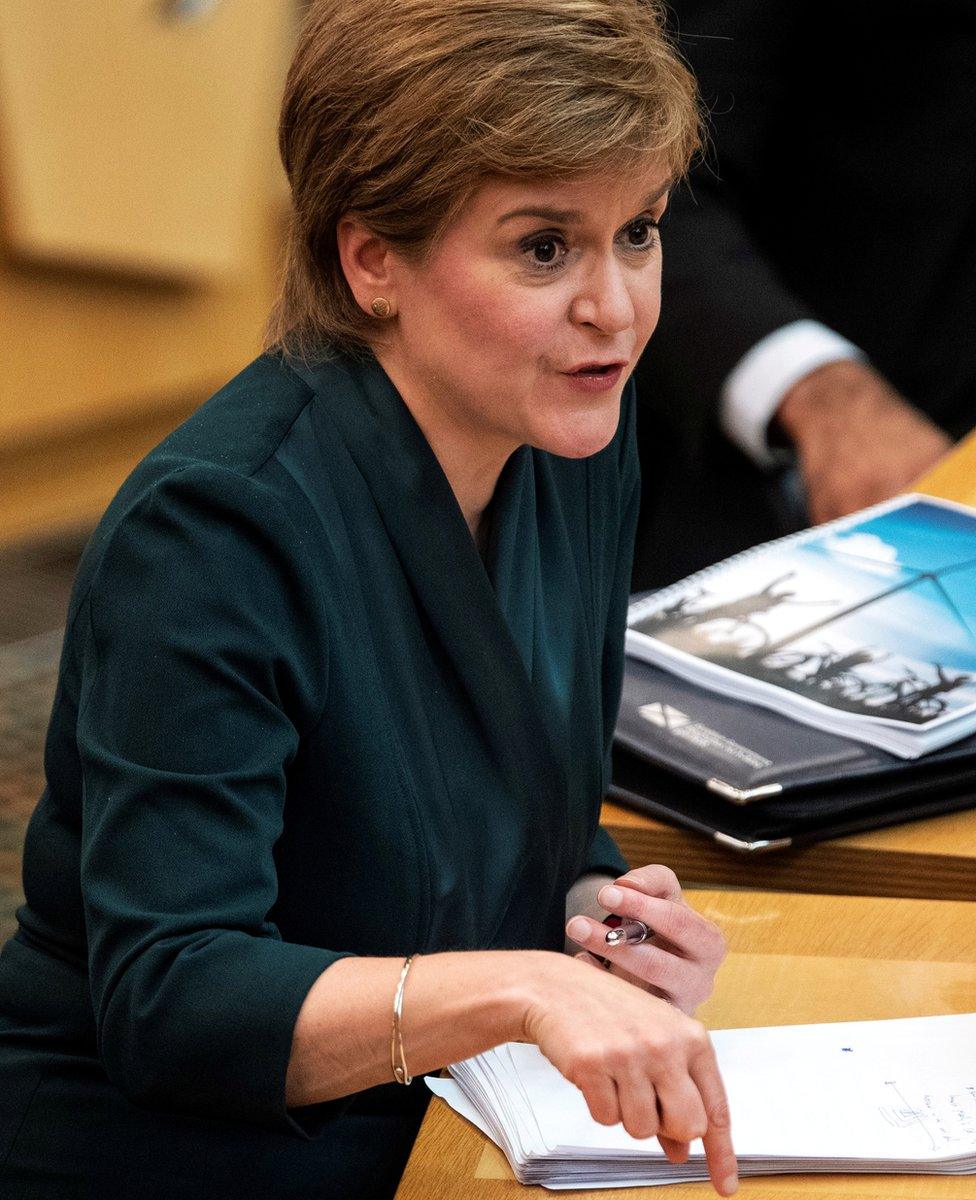

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon announced in her programme for government that a National Care Service is being set up

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon announced in her programme for government that a National Care Service is being set up, with legislation in the next year, and implementation within five years. A consultation began last month, and is still open to responses.

It is likely to bring together several aspects of the system, including regulation, and is proving controversial with some councillors who see it as a centralising power grab.

The main influence on it has come from a review commissioned by Scottish ministers and led by former civil servant Derek Feeley.

It recommended that self-funding people with assets should get the same level of personal and nursing support in residential care as those funded by the state.

The report identified a gap in the numbers that might have been expected to rely on care by 2018-19, when projecting forward from the level of support 10 years before. In other words, the assessment system has been applied in such a way that deserving people seem to be failing to qualify.

"There may be approximately 36,000 people in Scotland who do not currently have access to social care support and for whom it would be beneficial," the report concluded. "And it would cost about £436m to meet this need."

That's to close the gap that has opened up already. It doesn't cover the estimate from the Institute of Fiscal Studies that real increases in spending will be required to meet the demographic demands with nearly 4% extra each year.

The Feeley report also said that home care visits, for those who need them, should be free rather than means-tested. They are a particular problem in Scotland, both in terms of the quality of care given during short visits, and in the employment terms of home-care workers.

Feeley backed a significant rise in carer pay, at least to the Real Living Wage.

On the question of those with assets such as homes, and how much they should be expected to contribute to the costs of residential care, the Feeley review declined to offer an opinion.

Do Scots have to sell home to pay for social care? Is the system fair?

This looks like being a further divergence between the English and Scottish system. For those with assets of more than £28,000 in Scotland, there is no limit to how much they have to contribute to the system.

Only a small proportion of people remain in residential care for many years, but with costs running at more than £30,000 per year, after including government's contribution, those who do have assets can see them running down.

The implied view from Scotland is that they are unlucky not to be able to pass those assets on to their families when they die. But as someone has to pay the bills, it is fairer to charge elderly people with assets than to put an extra tax on lower earners.

The Westminster government has taken the opposite approach, using a tax on jobs, typically falling on younger people, to pay for care and protect the assets of older people who have them.

So there is a problem with using a jobs tax to entrench inequality between those who have assets and those who do not.

There is a further generational inequality with the new English policy about younger people on lower pay (throughout the UK) footing the bills for older people who could pay them.

There is a another dispute over the use of the National Insurance system, when income tax would be a more progressive option, catching more of those with unearned income and taking a bigger share of their earnings above £50,000 per year.

There was a Conservative Party promise at the 2019 election not to increase the rates of either.

One consequence that might be worth watching: if people with their own homes can be confident that they don't face catastrophic care costs in later life, it could lead to significantly changed behaviour in how they spend or even splurge, or pass on their money to others.

Related topics

- Published7 September 2021

- Published7 September 2021

- Published3 May 2021

- Published6 February 2021