NHS Scotland's 'biggest crisis' in five charts

- Published

- comments

Scotland's Health Secretary Humza Yousaf says the NHS is facing the "biggest crisis" of its existence.

There's a shortage of beds, the demand for ambulances is soaring and waits in accident and emergency departments are getting longer.

On top of that, Covid-19 admissions have been rising fast as the number of infections in Scotland spiralled at the end of the summer.

Here are five charts illustrating the enormous pressures currently being felt by NHS Scotland.

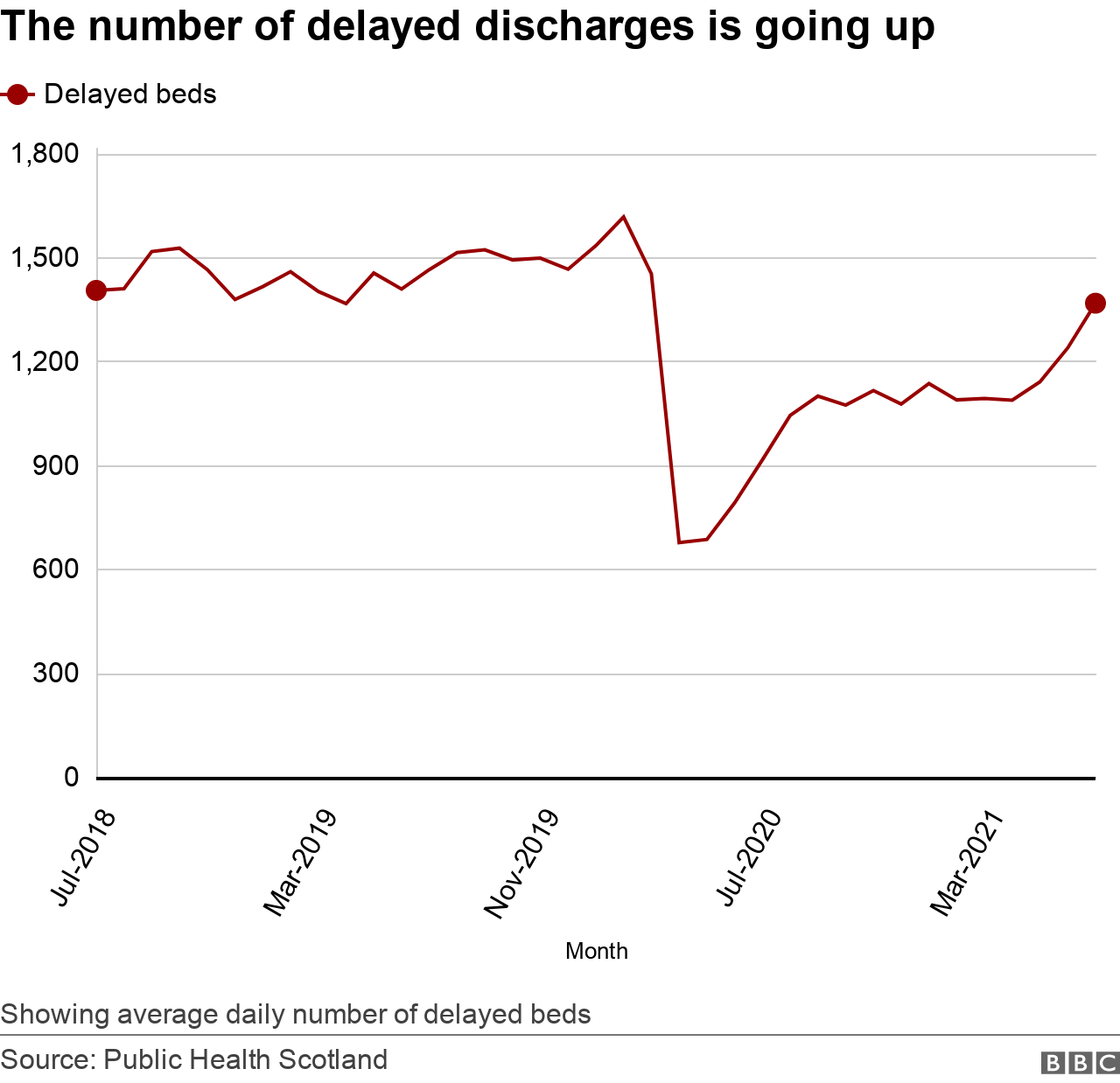

'Bed blocking' is an increasing problem

The efficient operation of the NHS is highly dependent on the ability to move patients out of hospitals once they've been treated.

If a treated patient remains in hospital then it can prevent another being admitted - a phenomenon known as "bed blocking".

Delayed discharges dropped at the start of the pandemic as the NHS suspended much of its routine services to focus on Covid-19 patients.

The figure began to rise again last summer before reaching a plateau this winter.

However, the number of delayed discharges began to rise sharply in the three months up to July - the most recent month there are figures for - and this trend is likely to have continued over the summer.

There are a number of reasons why treated patients might be delayed in hospital.

In July there were 42,364 "delayed bed days", with two-thirds being for "health and social care reasons".

Earlier this week Prof Michael Griffin, president of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, said there were real problems getting patients out of hospitals and into social care because of a "care home workforce crisis"

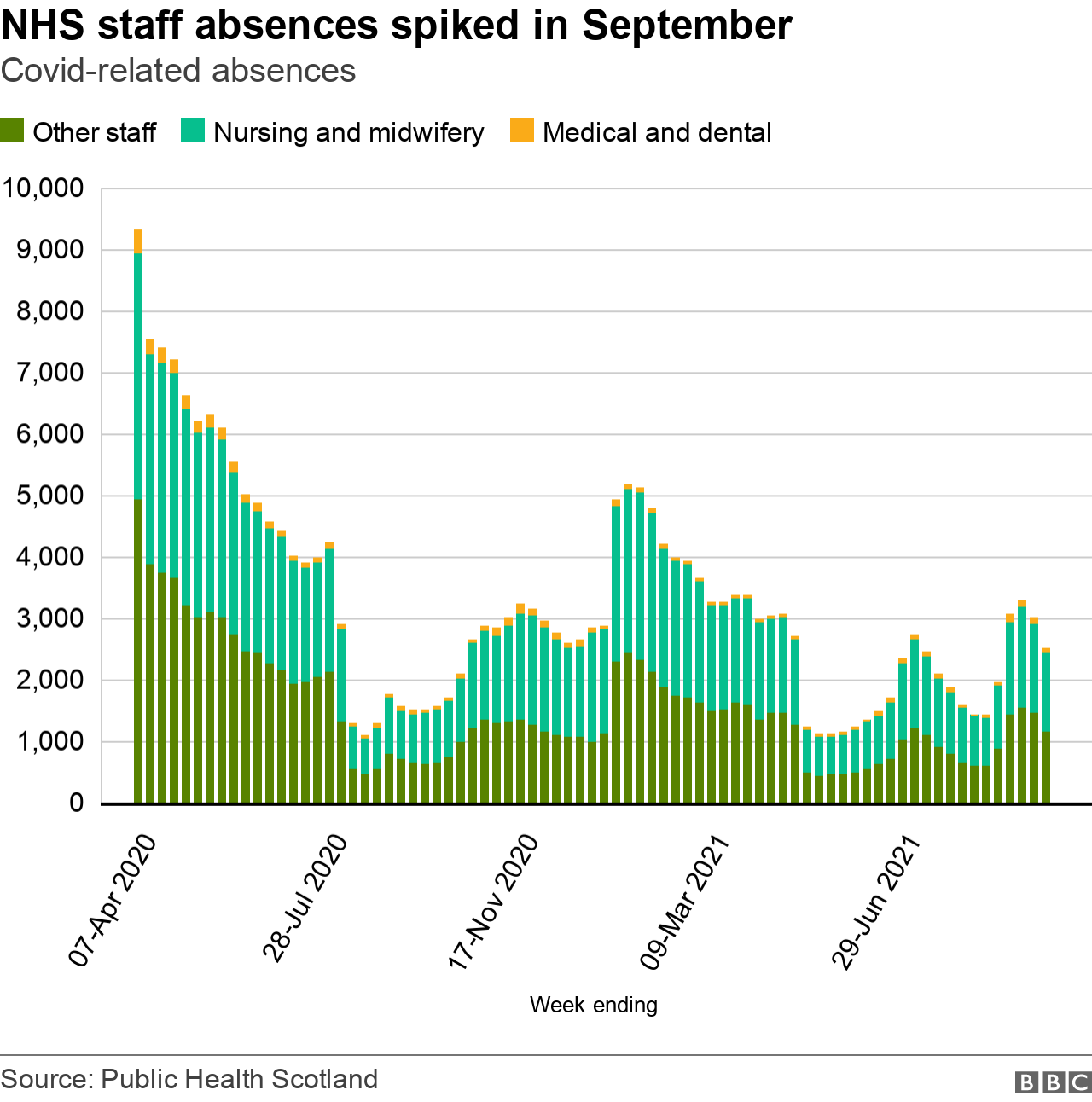

Covid absences among NHS staff still have an impact

It's not just care homes that have workforce issues.

The NHS was also hit by Covid-related absences as the number of cases spiralled across Scotland last month.

Recent changes to self-isolation rules have kept absences lower than the peak of the outbreaks in spring 2020 and this winter, but they still doubled between mid-August and mid-September.

The ambulance service is under increasing pressure

Last week, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said the ambulance service was "operating at its highest level of escalation".

The Scottish government has now enlisted the help of the Army, fire service, British Red Cross and taxi firms to ease the pressure.

Public Health Scotland publishes monthly figures on Scottish Ambulance Service incidents, comparing them with pre-pandemic levels.

For much of the year, ambulance incidents were down on 2018-2019, but began rising in the summer and are now higher than the pre-pandemic average.

The head of the Scottish Ambulance Service, Pauline Howie, recently apologised to patients for the longer waits, saying her staff were working under "unprecedented pressure" dealing with big increases in Covid and non-Covid calls.

This data spells out the problem facing the NHS - too much demand and not enough capacity.

Bringing the army in will help to free up some clinical staff to work on urgent calls. That might ease some of the pressure getting people to hospital, but nursing leaders warn the staffing situation is "desperate".

Even if you find more beds, they say there are not enough nurses to care for patients.

It's the same getting people home at the end of their treatment. Those working in social care say they too face a staffing crisis.

It also takes time to find space in care homes or to assess and adapt people's homes so that they can return safely.

These are long-standing issues for the health service but Covid has shown just how little give there is in the system.

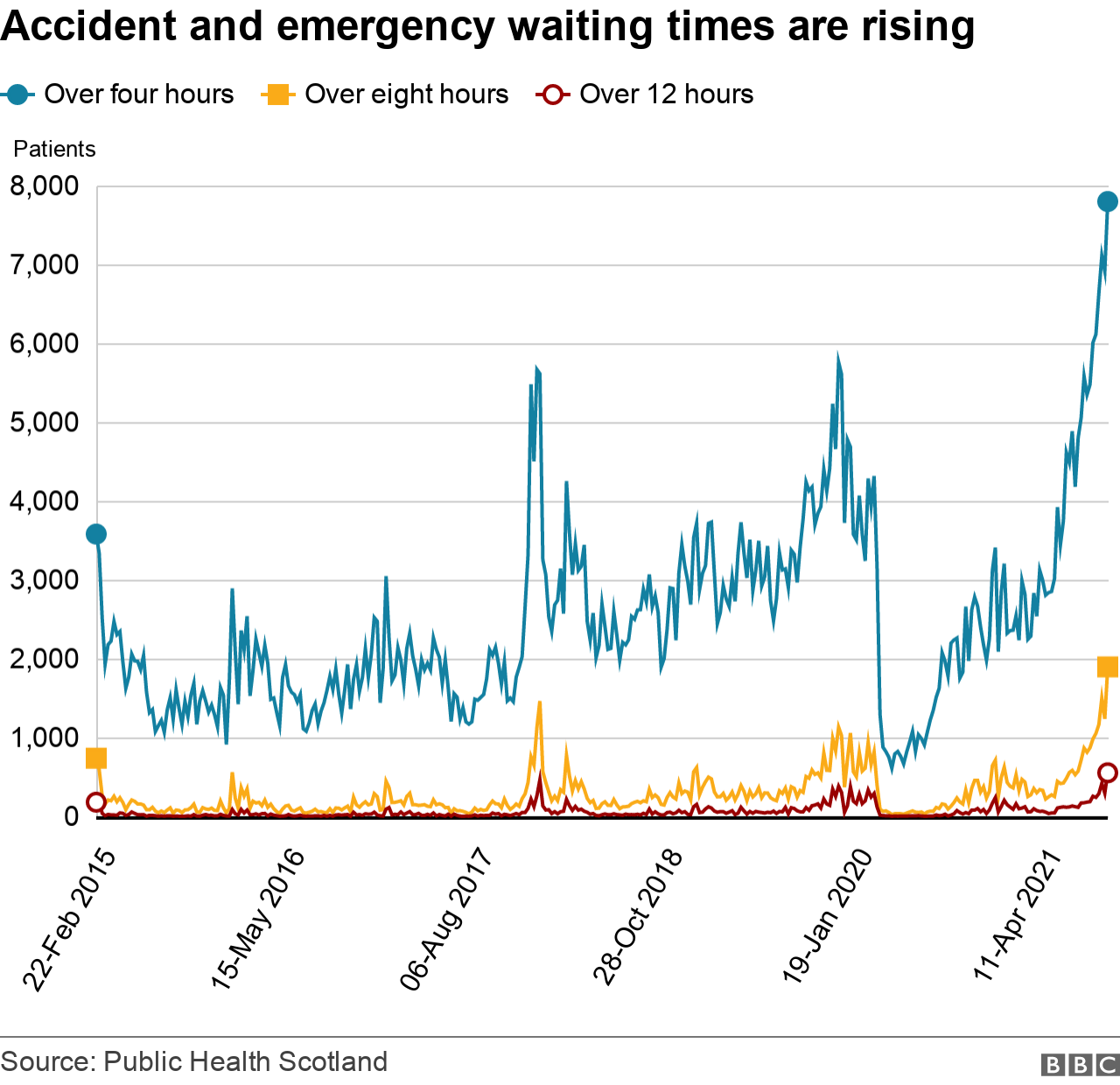

Emergency department patients are waiting longer

Accident and emergency departments are often thought of being a "barometer" for the rest of the NHS, acting as the hospital's front door for many patients.

One way to measure emergency department performance is waiting times - and it's obvious from these figures that all is not well.

There's a big drop in waiting times when the pandemic first hit in March 2020, as lockdown was introduced and emergency departments were suddenly much less busy.

But the number of patients waiting more than four hours in A&E began rising sharply in April.

The figure is now higher than it has ever been in the last six years and shows no sign yet that it is starting to go down.

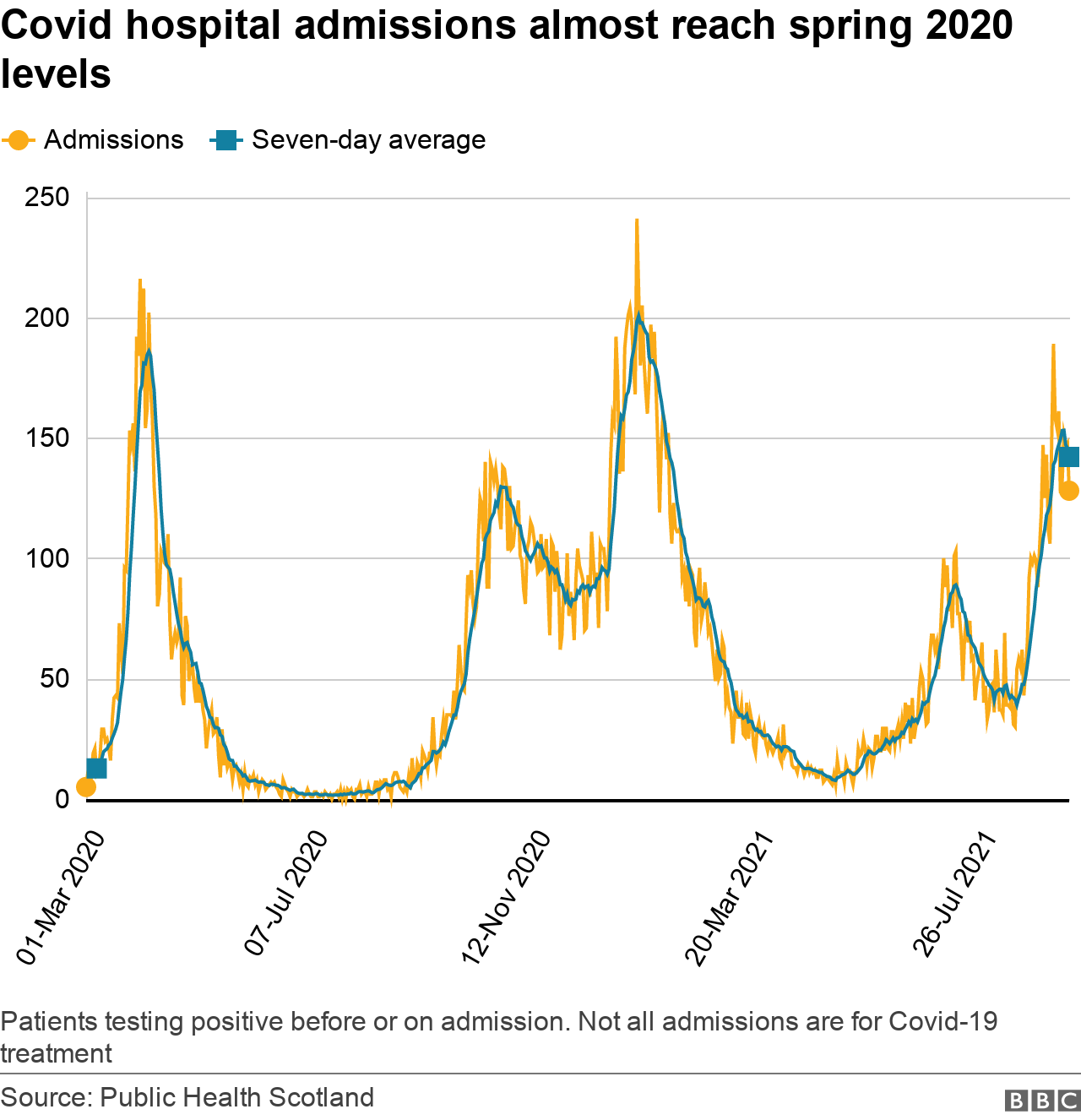

Are Covid admissions finally beginning to fall?

There is strong evidence that vaccination has weakened the link between Covid infection and serious illness.

Fewer people need hospital treatment, and those that do spend shorter periods in hospital.

But the link has not been eliminated and people are still being admitted.

The number of infections rose rapidly at the end of August and into September, and that rise was reflected in hospital admissions.

Average admissions are not at the same level we saw in January this year - but they're not far off the peak in April 2020, during the first wave of the pandemic.

However, the most recent figures show the first indication that daily admissions may have peaked and could now be starting to fall.