The twin threats of flooding and drought

- Published

Lorraine Watson says the floods hitting her chip shop have become more intense and more frequent

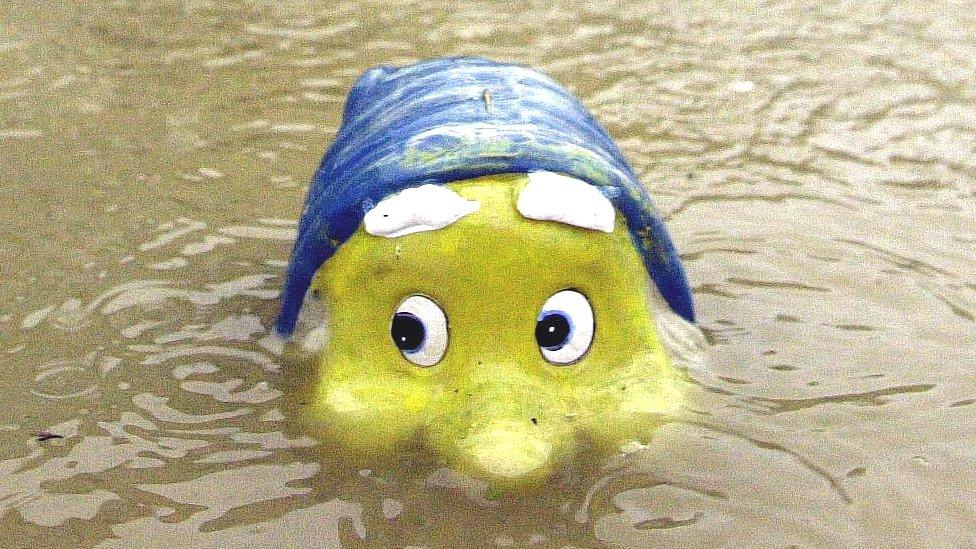

Lorraine Watson's chip shop has been badly flooded five times in 10 years.

The Carron fish bar in Stonehaven takes its name from the river which flows beside - and all too often through - its basement.

The last time that happened was in the early hours of 12 August 2020 when the spate lifted freezers from the floor and left behind a sticky, stinking soup of mud and grease.

The bill ran to £8,000, according to Ms Watson, who says the floods have become more intense and more frequent in her decade running the shop.

On the same summer's day, a train hit a landslide at Carmont just outside the town, killing the driver, a conductor and a passenger.

Is climate change a factor in Aberdeenshire's repeated, devastating floods?

"One hundred per cent" declares Ms Watson, adding: "We must take action. Everybody must take action."

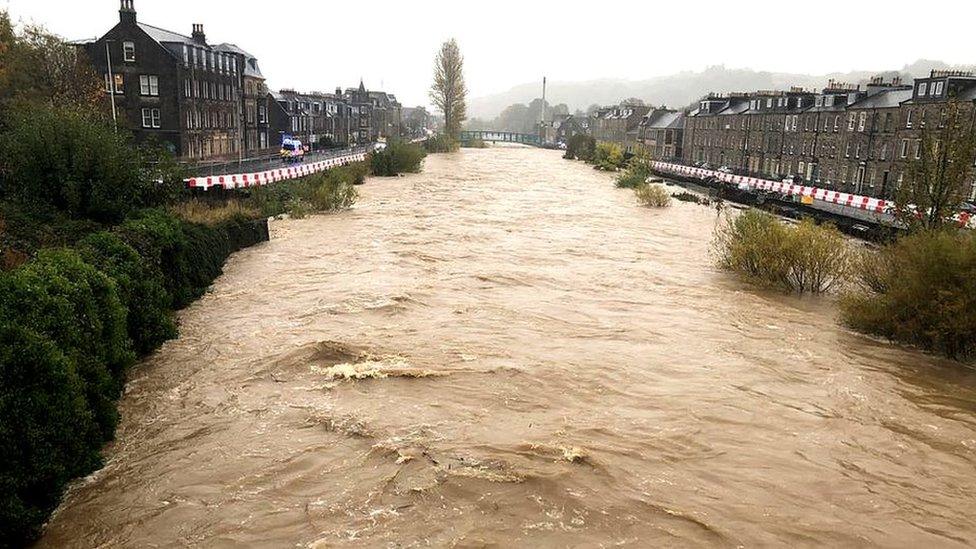

In fact Stonehaven, nestled beside a natural harbour on the North Sea, some 15 miles (24km) south of Europe's carbon capital, Aberdeen, faces not just one type of flooding but three, all potentially linked to climate change.

First there is the River Carron's propensity to fill with water running off the surrounding hills and then to burst its banks.

Secondly, even if the river does not overflow there is the threat of street flooding when downpours overwhelm the drains.

Thirdly, as a coastal community there are concerns about high tides, storm surges and the longer-term risk of rising sea levels.

To militate against the first threat - river flooding - Aberdeenshire Council is building defences which include raising bridges, re-routing the river, and building a hi-tech hydraulic wall which will slice through the middle of the town and should automatically rise even higher during the most severe floods.

The scheme has divided residents, partly on aesthetic grounds. It is also running late and it is costly, although exactly how costly the council refuses to disclose for what it says are contractual reasons.

Principal engineer Rachel Kennedy says you cannot build your way out of climate change

Nonetheless principal engineer Rachel Kennedy insists it will protect 820 people in 372 homes, along with a school, a police station and public utilities, external.

She agrees with Ms Watson that the floods here are growing in intensity and frequency because of climate change, citing a projection that by 2080 a third more water will be flowing down the Carron, external.

Although Ms Kennedy has raised the height of the flood wall to take that into account, she cautions that you cannot build your way out of climate change and stresses that the project is not a "silver bullet".

"This only protects from river flooding, it won't solve every problem," she warns.

And there are so many problems. Next year the UK government must by law publish the third in a series of five-yearly reports assessing climate change risks.

A summary of the situation in Scotland which has already been prepared for that report, external concludes that flooding is one of the most severe risks facing the country, posing a serious threat to infrastructure and representing "the costliest hazard to businesses."

By the 2050s, the experts predict, Scotland's temperatures will have risen by 1.1 degrees Celsius, while winter rainfall will have increased by about 7% in amount and as much as 25% in intensity, all compared to the period 1981 - 2000.

Summer rain storms are forecast to become rarer but heavier with a risk of flash floods but at the same time the nation may be grappling with the opposite problem - water scarcity as a result of a 7% drop in overall summer rainfall.

Stonehaven and Wick have much in common. Both are small east coast towns with a history of herring fishing and flooding.

The Old Pulteney distillery struggled because its water source dropped dangerously low.

This summer though the Caithness town's issue was not too much rain but too little, a problem felt particularly acutely at the local distillery, the home of Old Pulteney single malt, when its water source - Loch Hempriggs - dropped dangerously low.

You can't make whisky without water and in August, with the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (Sepa) issuing warnings about "significant scarcity" in Caithness, owners Inver House Distillers announced a suspension in production.

It was not a difficult call says distillery manager Malcolm Waring.

Distillery manager Malcolm Waring says they stopped production to protect the water source

"We want to protect the environment," he says.

"We want to protect our source. If we don't have that, we can't make whisky here. So the decision was an easy one to stop, let it recover, let it sustain itself."

The supply has since recovered, water is now pouring into the distillery again and Mr Waring is optimistic that the source can be managed sustainably although as the world warms the risk of another shortage is unlikely to recede.

According to Sepa this summer was Northern Scotland's fourth driest since records began in 1862.

Some public water supplies ran short, particularly in the far north and the south west, while more than 100 private water supplies struggled with scarcity, notably in South Ayrshire where 67 properties were affected for almost five months.

It was Scotland's second drought in just three years - in 2018 a dry winter combined with a lack of summer rainfall and record high temperatures led to restrictions on water use, wildfires and the death of many fish, external.

Not only was there a shortage during 2018 but the drought actually drove up demand for water by 30%, according to Sarah Halliday who lectures in geography and environmental science at Dundee University.

Dr Sarah Halliday says we must stop taking water for granted

"If it's very dry, farmers have to irrigate their crops," she says. "We all want to water our gardens, so we start using our hosepipes much more often."

Dr Halliday acknowledges that for many people in Scotland their personal experience of climate change so far is enjoying hotter summers - "everybody's got their paddling pool filled up," she says - but she thinks we must stop taking our water supply for granted.

To tackle both floods and droughts she recommends reducing the use of artificial grass and concrete; turning off the tap while brushing teeth; and limiting hosepipe use.

"Actually producing drinkable water that comes through our tap is a hugely costly process that also requires a lot of carbon emissions," Dr Halliday says.

"And the fact that we quite often stick a hose on that tap and pump it into the garden, it's a huge waste of energy and materials."

Public agencies are echoing some of that advice.

Scottish Water estimates that the nation's water usage amounts to 165 litres per person daily, with treating it and heating it accounting for 6% of carbon emissions, external, the same as the aviation industry.

Along with Sepa, which last year published Scotland's first ever National Water Scarcity Plan, external, it is urging people to conserve what is a vital resource.

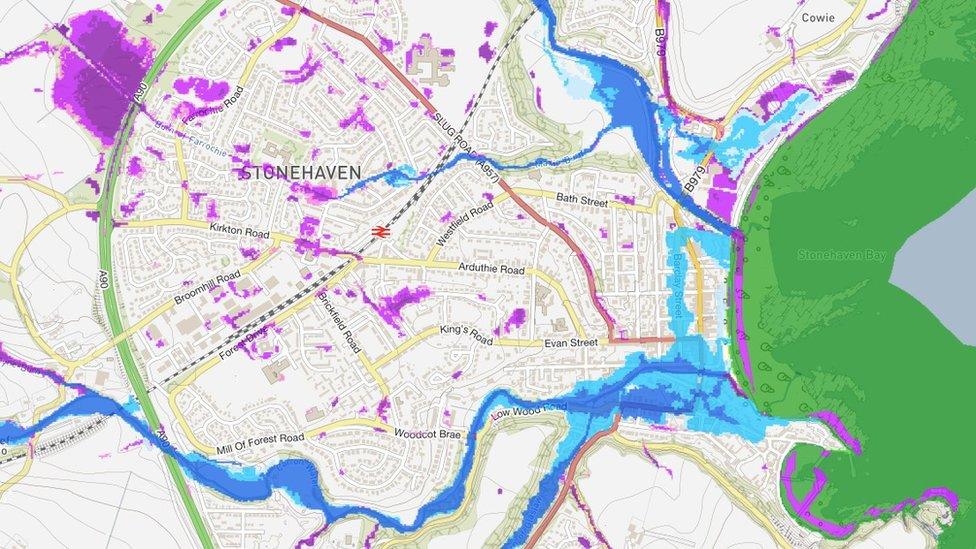

At the same time the environment agency is about to undertake what it calls a "wholesale update" of its flood risk mapping incorporating up-to-date climate change data.

Sepa's flood map show Stonehaven under threat (coastal flooding=green; street=pink; river=blue)

In the latest landmark UN report on the climate, external, water is mentioned more than 3,000 times.

For Lorraine Watson in the Stonehaven chip shop, that is understandable.

"Climate change for us is immense," she says.

"It isn't going away."

- Published5 November 2021

- Published29 October 2021

- Published2 August 2021