The war poet and the attractions of Milnathort

- Published

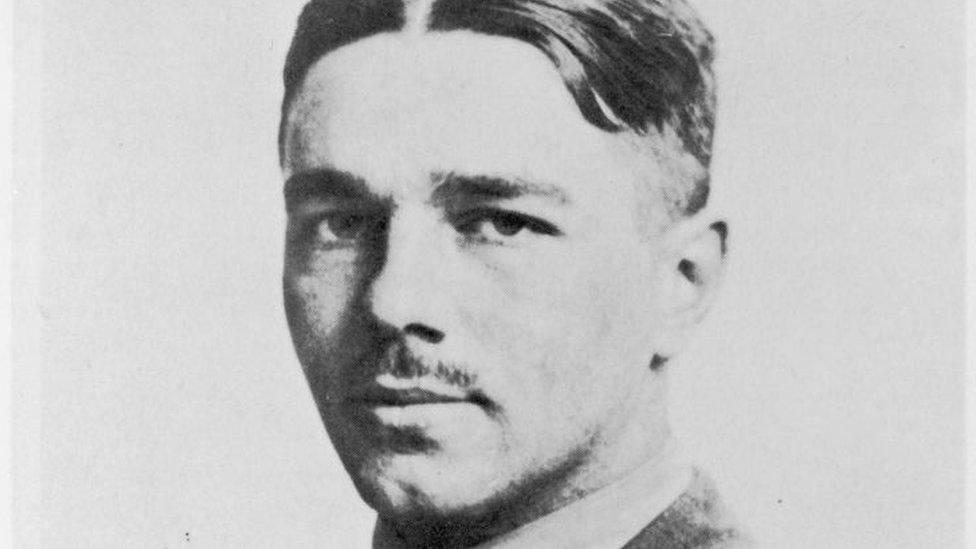

Wilfred Owen is regarded as the greatest poet of World War

Poet Wilfred Owen's link with Craiglockhart Hospital in Edinburgh is well documented but his regular visits to Milnathort in Kinrosshire are less well known.

Owen is regarded as the greatest poet of World War One. His works about the horrors of trench and gas warfare are still taught in schools today.

He was born in Shropshire in 1893 and was beginning to forge a career as a teacher when war broke out.

In 1917, while being treated for shell shock at Craiglockhart Hospital in Edinburgh, he taught English at Tynecastle High School in the city.

It was one of a number of projects which Owen was encouraged to take part in, to aid his recovery.

Neil McLennan, a historian from the University of Aberdeen, first made the connection when he was head of history at Tynecastle High.

"Owen was only in Edinburgh for four months, from June 1917, but Edinburgh was critical to him," Mr McLennan says.

"It's the most important period of his writing," he says.

Travelled the country

It was at Craiglockhart he met Dr Arthur John Brock, who encouraged him to write poetry, and Siegfried Sassoon, another war poet, who was also being treated there.

Mr McLennan says: "Owen wrote about a quarter or a third of his poems during his time in Edinburgh, including his most powerful, Anthem for Doomed Youth, and Dulce et Decorum est."

Thousands of soldiers were treated at Craiglockhart, and some were so damaged by their experiences of the war, they could not even leave their rooms.

Others, like Owen and Sassoon, were allowed to leave the hospital to work or to travel.

"They wore blue armbands to show they were serving soldiers, undergoing treatment, but they were able to travel around the country," Mr McLennan says.

"Siegfried Sassoon was a keen golfer so they went to North Berwick and St Andrews."

Albert Dauthieu and his family lived in Milnathort

But the two poets also made regular visits to Milnathort in Kinrosshire.

The visits were documented by biographers Dominic Hibberd and Jon Stallwarthy.

Milnathort had a golf course, which may have been the initial draw for Sassoon but for Owen, the village had another attraction.

"Albert Dauthieu had been the head chef at the Savoy in London and now ran the Thistle Inn in Milnathort," Mr McLennan says.

"The food would have been remarkable for two young men used to war hospital fare, and army rations."

But Albert also had two daughters, 19-year-old Albertina, and her younger sister Rose.

Albertina was engaged to a Scottish captain but she quickly became smitten with Owen

Rose was deaf and mute, and something of a mascot for local soldiers.

She collected autographs from visitors in a book, which is now in the Craiglockhart Collection.

Albertina was engaged to a Scottish captain, but she quickly became smitten with Owen.

"The story goes that Albertina was taken with Owen, and the feeling was mutual," Mr McLennan says.

"According to her family, it was agreed that whoever returned from war first, would take her hand in marriage."

Sadly, neither man returned from the war. The young captain died in March 1918 and Owen the week before the war ended. He was just 25.

The telegram was delivered to his parents in Shropshire on 11 November 1918 as the bells rang out to mark Armistice Day.

'Re-examination of his work'

Owen's sexuality has been the subject of much speculation. His friendship with Siegfried Sassoon, who had affairs with several men, and with Edinburgh translator CK Scott Moncrieff who dedicated several works to Mr WO, simply added to the narrative.

Mr McLennan believes the latest information leaves open the possibility that Owen was heterosexual or bisexual.

"Romantic undertones are a key part of his poems," he says.

"The assumption had been that these had homosexual connotations but this changes things, and will hopefully lead to a re-examination of his work."

Owen's poems were published posthumously. He left a list of 25 people who were to receive first editions, should they ever be published. Five of them were in Edinburgh, including Dr Brock, who first encouraged him to write.

And among the collection The Ballad of Many Thorns, which seems to reference Milnathort and the French family with whom he found a brief moment of happiness before returning to the horrors of the Western Front.

"I hope the village of Milnathort can now have this strong connection and pride in Wilfred Owen" says Mr McLennan, who is writing a book about Owen's time in Scotland, which will be published next year.

"For history, it's an important moment, because more than 100 years after the end of the First World War, it shows there's still much evidence to be unearthed and interpreted to help us better understand that era."

Related topics

- Published26 June 2017