Assisted dying: 'I wish my wife had been allowed to end her life'

- Published

Leighanne, left, said her wife Gill suffered a prolonged, painful death

Leighanne Baird-Sangster says her wife, Gill, suffered a prolonged, painful death.

She is now "a big supporter" of allowing terminally ill adults to choose to end their lives with assistance from doctors.

But others say the medical profession should not assist people who want to die, and instead should provide better palliative care.

A public consultation is gathering views on whether the law should change to allow medics to help terminally ill, mentally competent adults to end their lives.

Leighanne says Gill received palliative care for cancer in May 2020.

Gill died at the age of 44. Her final 10 days and the pain she endured in that time have had a devastating and lasting impact on her widow, who still lives in Corstorphine in Edinburgh.

"Gill was terminally ill with melanoma cancer," Leighanne said.

"When she reached the end of life stage, we had a brutal 10-day period after which she did die - and sadly not as peacefully as sometimes it's made out to be."

Leighanne, 42, says she supports the Assisted Dying Bill, put forward in the Scottish Parliament by Lib Dem MSP Liam McArthur.

She told the BBC's Eorpa programme she wishes her wife's final days could have been different.

"To be able to know when you want to say your goodbyes, to be able to choose what to do on your last day, if you're fit enough to do so, or even who you see and who you're with when the time comes - to give that element of control back to our terminally ill patients, to me that is exceptionally important," she said.

"I still have those moments when I think how is she not here? You still expect her to come in and light up the room, and that doesn't happen anymore," she said.

Sanctity of human life

Others do not agree that the medical profession should assist people who want to die.

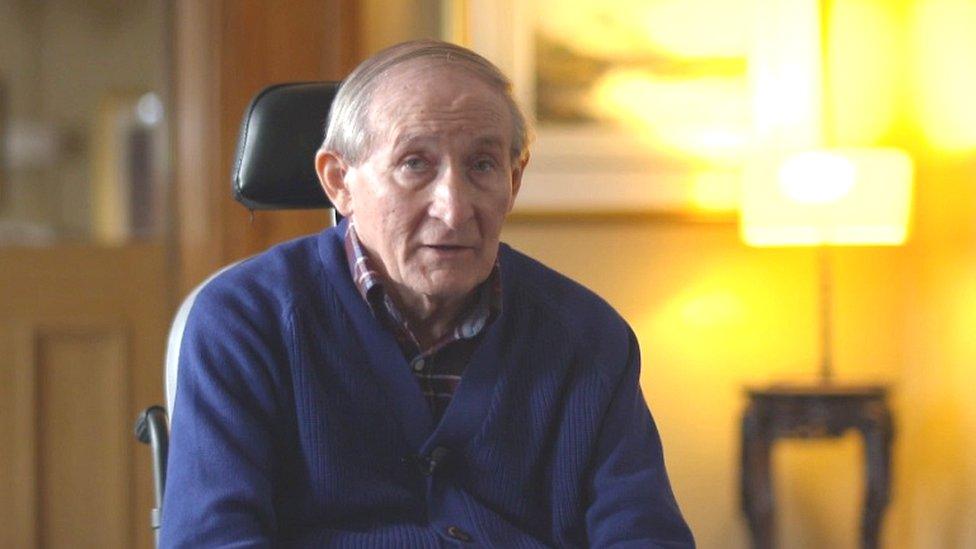

Donald MacDonald, who is now 77 and also lives in Edinburgh, practiced as a surgeon and a minister for many years. He is also a former Moderator of the Free Church of Scotland.

He now has MS. He believes allowing people to end their life deliberately goes against a key principle of medicine to first do no harm.

He told the BBC he believed "in the sanctity of human life" and that it was not right to end an innocent human life.

Mr MacDonald said: "I am fortunate that my disability came on gradually and I have been able to adapt at this stage of deterioration.

"This gives me confidence that God has given me strength to cope with further deterioration and with the end stage of life."

He said he did not think most disabled people would support the bill, and ensuring people had proper support and palliative care was a better option.

Donald MacDonald has MS but does not want an assisted death

This is not the first time assisted dying has been debated at the Scottish Parliament.

A similar bill was put before Holyrood by the independent MSP Margo MacDonald, but she died from Parkinson's disease before a debate could be held. In 2015, the bill was defeated.

Since then, some MSPs have been striving to get another bill on assisted dying put forward.

The bill - brought forward in June - proposes that in Scotland, it would be up to the patient to take the final lethal drug, and no other person would be allowed to administer it. The patient would also have to be an adult who lives in Scotland only.

Anyone who wished to have an assisted death must have a terminal, incurable illness, and must be deemed near the end of life. Although there is no recommendation yet on how long someone might naturally have left to live.

Ally Thompson, of Dignity in Dying Scotland, said the current blanket ban was "unfair and unjust"

Ally Thompson, of Dignity in Dying Scotland, said the current blanket ban was "unfair and unjust", causing many dying people and their families to "suffer needlessly".

"There is a better way and that is to legalise assisted dying for terminally ill, mentally competent adults," she said.

Ms Thomson said even if there was an excellent palliative care provision, some people would "still face a potentially very bad death".

Gordon MacDonald, of Care Not Killing, was worried that the provision could be extended

But Gordon MacDonald, of Care Not Killing, said the "vast bulk of countries" did not allow people to end their own lives.

He said in jurisdictions where the law has changed, there were "trends developing" for more and more people being eligible to end their own lives.

Mr MacDonald continued: "Vulnerable people, people who might feel themselves come under pressure maybe from themselves or maybe internal pressure rather than from a relative or it could be from a relative or health professionals."

He said people may feel themselves being a burden and therefore might opt for ending their life "for the wrong reasons".

If you or someone you know is struggling with issues raised by this story, find support through BBC Action Line.

- Published5 July 2021

- Published20 June 2021

- Published27 May 2015