The visually-impaired artists sharing their world

- Published

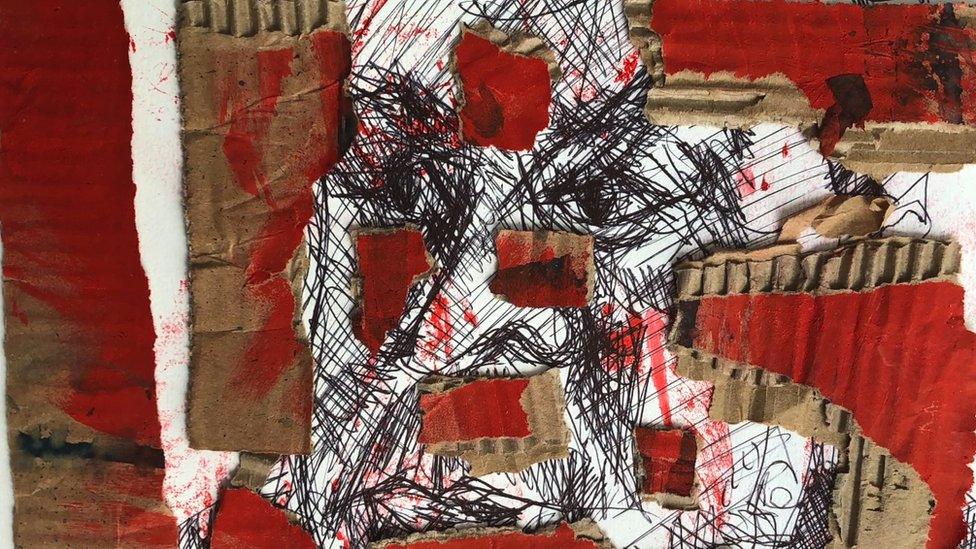

Willy Gilder is among the visual artists whose work features in the new exhibition

A new online exhibition is aiming to raise awareness of cerebral visual impairment (CVI) and help support children with the condition.

CVI causes a visual world that can be confusing, cluttered and disorientating, however, it is significantly undiagnosed.

One recent study found it affects about one child in every mainstream class.

Prof John Ravenscroft said most people believe that what we see is dictated by the eyes.

But the director of the Scottish Sensory Centre told BBC Scotland: "Actually most of the brain or 40% of the brain is dedicated to visual processing.

"And so, if you have damage to the visual parts of the brain, that are dedicated towards vision and visual processing, then you're going to have damage in understanding and processing what you see."

The result is CVI, which is effectively visual impairment due to damage of the brain.

Children with the condition typically only focus on one thing and find it difficult to switch attention to something else.

Some also find it challenging to look and listen at the same time while another red flag is becoming overwhelmed in noisy situations, such as a supermarket.

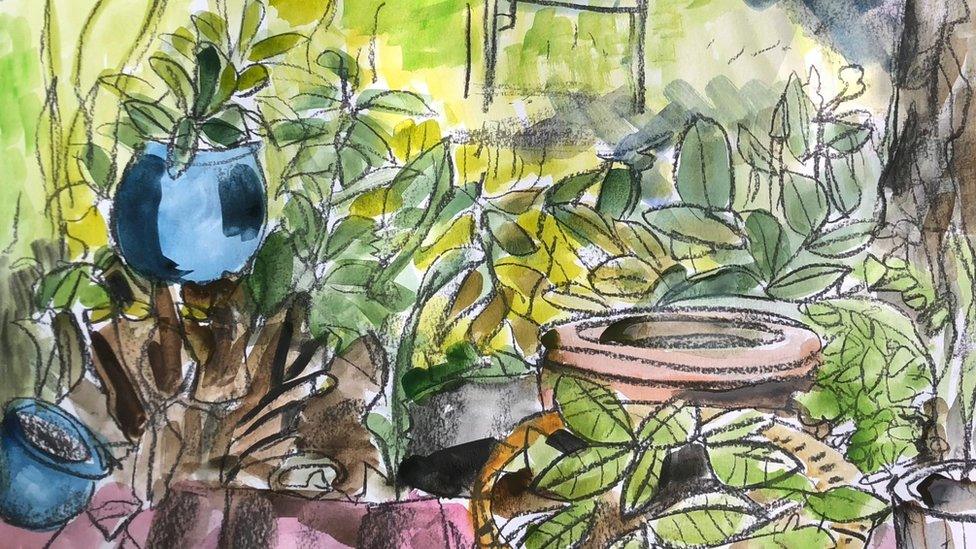

Visual artist Kendall Cowle's first realised there was a problem with her vision during a life-drawing class at art college

Prof Ravenscroft, of the University of Edinburgh, said it can be misdiagnosed as autism or ADHD but when it is identified it can make a "world of difference" to children as it should enable them to access specialist support.

Visual artist Kendall Cowle's condition wasn't diagnosed until she was a 21-year-old art student.

She first sensed something was wrong during a life-drawing class.

Ms Cowle said: "I started to realise that from the people that stood next to me, I was drawing the life model with an arm.

"Clearly we couldn't see it from that angle because no other people around me could see this.

"So my drawings of the life model were weren't truly accurate because my brain kind of made bits up, if that makes sense".

Explaining her condition, she added: "It's difficult. People say to me 'Oh, you suffer from a vision loss'.

"And I kind of go, 'I don't actually, I never lost anything. It was never there to begin with.'"

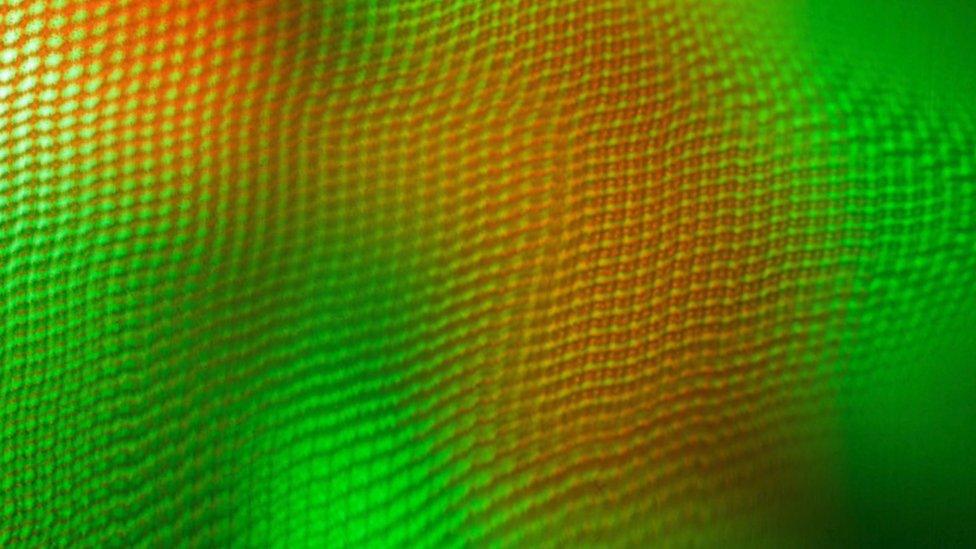

Kendall Cowie's work features in the new exhibition

Ms Cowle, whose work features in the exhibition, also recalled how she would put people in the middle of her camera frame only to find out they were on the right or not even in the picture.

She said most of the images she creates are abstract and designed to challenge the perception of the viewer.

Ms Cowle added: "So sometimes, you know, you're looking at shapes and colours, you might not be quite sure what you're trying to look at.

"It can be interpreted however the viewer wants to but, also, that there's a very much a representational aspect of the ever-changing nature of my own vision."

Ms Cowle uses her camera for her work as it narrows her visual field and reduces clutter.

She said: "Sometimes I can walk around with a camera and I'm not actually taking any pictures."

Prof Ravenscroft said another artist, Alfie Fox, had interpreted his world through his black and white photographs featuring doorframes.

He explained: "It becomes this cluttered multi layered, visual scene. So instead of just seeing a very clear doorway, he sees lots of doorways that are that are layered over each other.

"That is different to how we would see the world."

Alfie Fox's photography features blurred doorframes

The professor of childhood visual impairment also championed the value of Willy Gilder's work.

The academic said: "He has a viewing of landscapes and of drawings that are very simplistic and very clear. They're not as detailed as we see in the visual world.

"And so he's highlighting the salient features, the main features of what he sees when he's drawing."

Willy Gilder's work is known for its striking colours

Prof Ravenscroft said: "By combining that use of science by combining the use of art, I'm hoping to get that complexity across and for parents and professionals to understand just how difficult it is and interpreting exactly what that child with CVI sees."

The exhibition can be viewed on the CVI Scotland, external website or via the Scottish Sensory Centre, external website.