Scotland: Making its way in the world

- Published

Tech firms, such as those involved in tidal turbine design produce high productivity but low jobs growth

The amount workers produce per hour is the main driver of our standard of living, and it's been growing very slowly or stagnating

A new study of Scotland's productivity sheds light on improvements relative to the rest of the UK

There are wide variations across Scotland - notably between Edinburgh and the west - and a poor position by international standards

Report highlights a need for governments to get results on productivity, but puts even more emphasis on the lack of business investment, with big gaps in digital and management skills

We need a better word for 'productivity' - something that isn't such a turn-off to non-economists, and which conveys its vital importance to our economic health.

It isn't everything in determining the prosperity of a nation, but it's quite close to everything.

Whether a nation or a city or town, we need a high level of output per hour worked to justify our high level of living standards - relative, that is, to much of the rest of the world.

And we need that level to be rising if we are to enjoy a sustainable rise in those living standards, and if we're to avoid becoming a relatively poor part of the world.

So don't let the word put you off. This stuff really matters. Getting productivity right is hugely important.

Capitals stand out

Unfortunately, we're not getting it right. New research casts a spotlight on the productivity problems Scotland has, throwing up solutions that business and government need to address.

It's published by the Productivity Institute,, external based at Manchester University and working with the business school at the University of Glasgow. The lead author, Professor John Tsoukalas, is at Glasgow.

Funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, the Institute has been looking in detail at the nations and regions of the UK to find out why productivity is such a deep-seated challenge for so much of the UK.

It used to be masked by the high productivity of the financial sector, particularly boosting London and the South-East. But since the financial crash of 2008, UK productivity has stagnated.

To understand better what's been happening in Scotland, let's start with the good news. It has improved productivity over the past two decades at a faster rate than any other nation, or region of England.

Scotland is close to the UK average for productivity, and ahead of all other parts of the UK other than London and the South-East.

To put some numbers on that, Scottish output per hour (or gross value added, to be pedantic) stood at £34.60 in 2019, and the UK's was at £35.40.

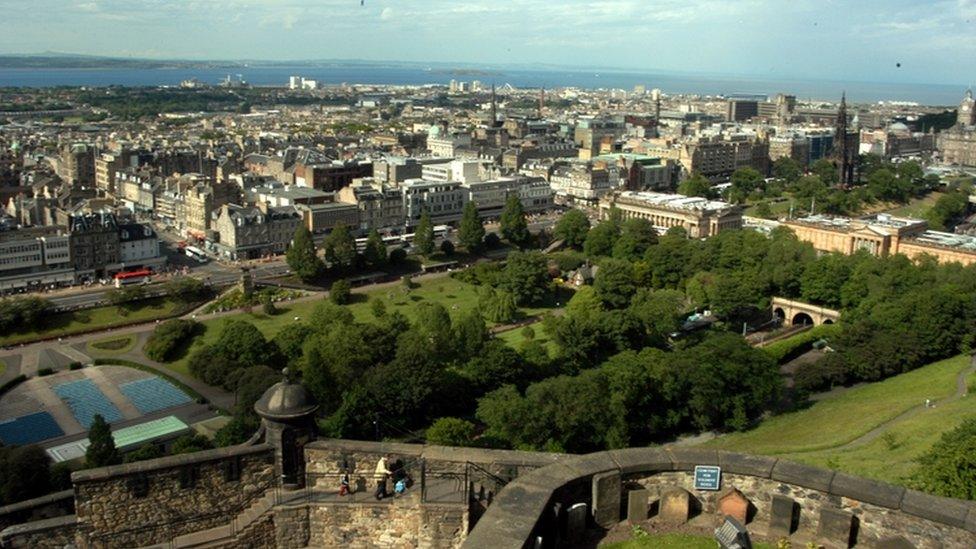

Edinburgh's financial services, universities, centre of government and technology bolsters productivity compared to the rest of Scotland

However, London's economy has been consistently 30% more productive than the UK as a whole, and south-east England nearly 10% more productive. Everywhere else is below average: Northern Ireland furthest behind.

Over those two decades, Scotland has moved ahead of the east and north-west regions of England. A lot of that has to do with the oil and gas sector making north-east Scotland one of the most productive parts of the UK. That is a declining sector, however.

It also has to do with the strengths of the Edinburgh economy, across professional services, finance, administration, its universities, government and increasingly in technology. On the productivity measure, Edinburgh scores £41.90 of output per hour worked (remember the Scottish average was £34.60).

So the capital stands out from the rest of Scotland in much the same way that London does from the UK.

Crofting vs banking

The new research gives a lot of detail on how different parts of Scotland have been faring. It shows cities doing relatively well, but also shows that Edinburgh's productivity has been 35% higher than Glasgow's.

Falkirk council area comes second to Edinburgh, which probably has to do with output from Grangemouth petro-chemicals. Manufacturing in Livingston helps West Lothian look good, and Perth and Stirling are above average.

Those trailing furthest behind the Scottish average include north and east Ayrshire, the west Highlands and Argyll, with figures that were not only poor but falling further behind the rest of the country.

The Borders council area does worse still, though it's growing in line with the rest of the nation. At the bottom of the league table - on £28.30 of value added per hour worked - i the Western Isles.

That should not surprise us. Productivity arises from factors of production. Crofting on poor quality land with seasonal self-catered tourism was never going to match productivity from corporate lawyers and asset managers in Edinburgh New Town.

Global ambition

So we know that there are wide variations around Scotland, and that Scotland fares well relative to most other parts of the UK, while also improving relative to those English regions.

However, doing better than the UK is not good enough, if the UK is doing badly - which it is.

The Scottish government has a target of getting Scotland into the top quarter of developed nations in the OECD club of developed economies. But it's been stuck in the third quartile, below the mid-way point - just below Japan, with its prolonged growth stagnation, and just ahead of Turkey, Slovakia, Slovenia and Lithuania.

With the exception of Portugal, the whole of western Europe was more productive per hour worked in 2019, as were the USA, Australia and Canada. And if prosperity counts for anything, that's the club Scotland needs to keep up with.

Narrow exports

Some of the reasons for Scotland's problems are all too familiar to those who have looked at the productivity challenges before. And some of them are being addressed.

You probably know that Scotland has a relatively low level of business start-ups. Yet there's a lot of effort put into entrepreneurial activity, and there have been some signs of that improving, slightly.

Scotland has a low level of business investment in research and development. That is particularly striking when contrasted with high levels of investment in university research.

That gap has been evident for decades. Why? It seems to be a reflection of Scottish-based businesses being biased towards low-productivity sectors, such as hospitality, tourism and food processing. These are not the sectors where business managers pile funds into university research.

Hospitality is a key part of the Scottish economy but it is a relatively low-productivity sector

A further problem is the lack of business scale-ups. Scottish business owners tend either to be satisfied with the market share they have, or they sell their companies to other companies, usually based elsewhere, for others to seize opportunities for growth in foreign markets.

As a consequence, Scotland loses the high value head office jobs, and it has a relatively low share of its economy in mid-sized, home-grown firms. It relies on very few companies for its exports: only 100 firms account for 60% of overseas sales, and many of them are headquartered outside Scotland.

A further consequence brought out in this report is that there are shortcomings in the management skills needed for growth of firms. In other words, our bosses could be more skilled at getting more out of investment, research, product development and their employees. Without the foresight for the right training, there are significant skill gaps in the workforce.

And there's a further observation about skills. Scotland scores very highly on graduate level skills, but it has an unusually high proportion of people - 10% of the workforce - who have no qualifications at all. That's a particular feature of Glasgow.

Better bosses

So what is to be done? The easy thing to do is tell government to step up its policy response. There could be better incentives to invest, which are mainly controlled at Westminster. There could be better development of skills, particularly digital ones, plus better infrastructure, support for business start-up and business growth, which is mainly for Holyrood and councils.

That message to governments is included in this report, calling for better collaboration between public sector tiers, and a message with a familiar look to it: "Instead of creating too many new different strategies and action plans, it is important to focus on delivery and implementation".

There's a conundrum highlighted too. For governments wanting to see jobs growth, the best results are not in the sectors that are seeing productivity growth. The authors of this report note that tech firms deliver high productivity but low jobs growth, while the real estate sector is doing the reverse.

Likewise, investment into rural areas can support jobs there, but it's in the cities that productivity results can be chalked up.

But the key to cracking the productivity puzzle is in getting business to raise its game, and that starts with investment - in equipment, buildings and workforce skills.

This week's report quotes the Fraser of Allander Institute in suggesting that matching the UK average for business investment, each Scottish business with more than 50 employees would need to invest an additional £55,000 per year. And part of that could be investment in becoming better bosses.