Scottish Ballet revises The Nutcracker to address racism

- Published

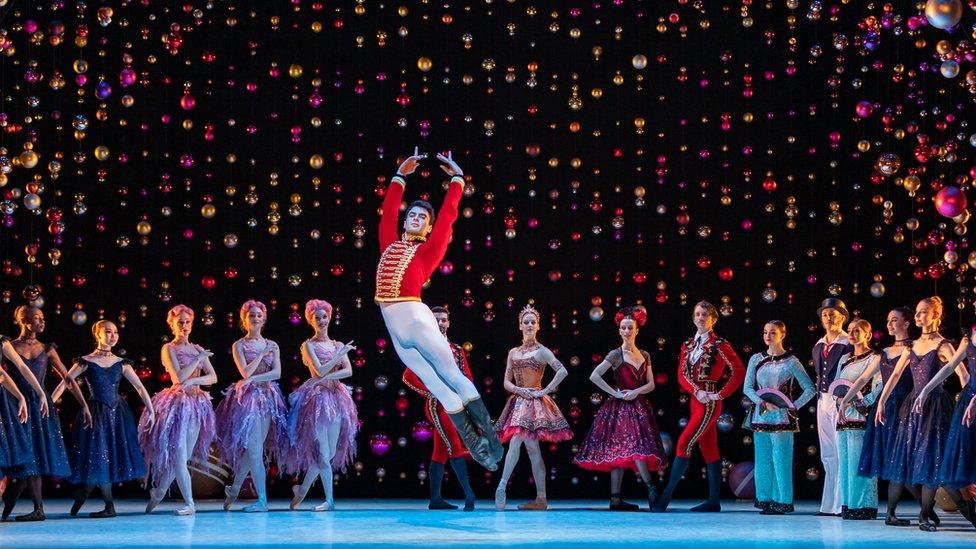

The Nutcracker is the biggest production Scottish Ballet has staged since the pandemic began

For many people, a trip to the theatre to see the ballet The Nutcracker is as traditional as it gets. A magical tale of toys that come to life, dances in the snow and a majestic score by Tchaikovsky.

It is to ballet companies, what pantomime is to theatres, and after a period of absence because of the pandemic, it couldn't be more welcome.

But The Nutcracker has become increasingly problematic for ballet companies, particularly those, like Scottish Ballet who are keen to stand up against racism in the industry, as well as encouraging diversity in their own organisation.

Created more than a century ago, its central characters are like the audience for which it was intended, wealthy and white.

The show is centred around heroine Clara

That's an issue which will gradually be resolved by blind casting. But the dancers have to be there in the first place, and for the past decade, many commentators have continued to criticise the industry for its lack of encouragement and inspiration.

French dancer Chloe Lopes Gomes called out Germany's Staatsballet - where she was the first black ballerina - for demanding she wear white makeup in a production of Swan Lake.

Earlier this year, she won her case and had her contract renewed. She described it as a wake up call for an industry which was still "closed and elitist".

"Commitments come easily through writing or speaking, so our most important commitment to help drive anti-racism is action," says Scottish Ballet's CEO and artistic director Christopher Hampson.

To that end, he's made some small but subtle changes to the 2021 production of The Nutcracker, which opened at Edinburgh Festival Theatre this week.

The second act contains the Land of the Sweets where various characters perform set piece dances for the heroine, Clara.

The Arabian dancer which appears in Clara's dream

There are Chinese dancers, an exotic Arabian dancer and of course, the famous Sugar Plum fairy. They're all characters in Clara's dream, so not meant to be entirely realistic but the undercurrent of racism has not gone unnoticed.

In 2013, Ronald Alexander of the Harlem School of the Arts wrote in Dance magazine that they were "borderline caricatures, if not downright demeaning."

'We want everyone to feel celebrated'

Scottish Ballet brought in Chinese choreographer Annie Au to work with the dancers on a more authentic fan dance. Pointe shoes are ditched. The two dancers are in flats to allow them to perform the intricate footwork.

It might seem like a small effort, but there were elements of the original dance which were actually offensive to Chinese patrons.

Performers wear flats rather than traditional pointe shoes during the Chinese dance

The "queue" or traditional ponytail was a symbol of submission to the Manchu rule and not having one was considered treason.

"Early Chinese Americans were literally lynched and hung up in trees by their own hair" says the dancer and writer Phil Chan, who co-founded the campaign Final Bow for Yellowface.

It aims to eliminate racist stereotypes in ballet productions, and Scottish Ballet was one of the first companies to sign.

Mr Hampson said: "When people are in an audience, and see a representation of their culture on stage, at Scottish ballet, we want that to be a positive experience.

"We want everyone to feel welcome to come see a performance, and to feel represented and celebrated."

The Arabian dance costume has also been altered slightly, and the character of Drosselmeyer the magician is played on alternate nights by a male and female dancer.

The show aims to tackle gender stereotypes by casting a female Drosselmeyer on alternate nights

"Art must evolve to speak to our times, which is why our Drosselmeyer will be played by male and female dancers," says Christopher Hampson.

"I made this change after considering who our heroes are in ballets, and it struck me that there was nothing about this role that suggested only a man could deliver it.'

Mr Hampson points out that every version of the show since it was first created for Scottish Ballet by its founding director Peter Darrell, in 1972 will have had changes made.

How does he know this? Because he and his team have been working with the National Libraries of Scotland and the Scottish Theatre Archive, to examine the company's production history. Which may help them with future shows too.

The famous production includes the return of a live orchestra

Already, he's looking towards next year's production of the Snow Queen, and hopes to have conversations with representatives of the Gypsy, Roma and traveller communities about any changes which might be needed.

Change is happening, slowly, onstage and off, some of it so subtle, you might not even notice it's there, like the bronze and brown shoes and tights created for black, Asian and mixed race dancers.

Scottish Ballet was one of the first companies to use the range, and they now promote it to their young Associates programme.

And that's an important point. This is the biggest production Scottish Ballet has staged since the pandemic began, and includes the return of a live orchestra.

As well as the company, they'll have students in training from the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, and a cast of 40 children drawn from across Scotland.

For them, this isn't just a traditional show. It could be the entry point to a career in dance and Mr Hampson wants to make it clear that it is open to anyone.

He said: "The Nutcracker was created in 1972, when it was acceptable to represent other cultures through imitation. If we are representing a culture, it's important that we have done our due diligence to ensure it is done so authentically. By rectifying inappropriate cultural stereotypes, we're adding to the production's heritage and making it richer."

- Published23 April 2021