The challenge of tracking seals around tidal turbines

- Published

Harbour seals could be affected by the tidal turbines under the water

The push for tidal power is bringing a new set of questions for those developing the green energy technology: Are marine mammals such as seals going to be affected?

Tidal energy generation can come in different shapes and sizes but in basic terms, what we are talking about is sinking turbines underwater - some the size of a bus - with rotor blades propelled by the power of the sea to make renewable electricity.

In much the same way that the development of wind turbines brought a concern for birds, experts need to make sure that wildlife is protected from the new green energy technology of tidal power.

This is why an innovative new monitoring device will track the fine-scale movements of marine mammals around these underwater turbines.

The monitor - developed by the Sea Mammal Research Unit (University of St Andrews) and the MeyGen Tidal Stream Energy Project - is robust and extremely heavy so it doesn't turn into tumbleweed on the seabed.

One of the test project turbines being lowered into the sea

On board are two types of sensors.

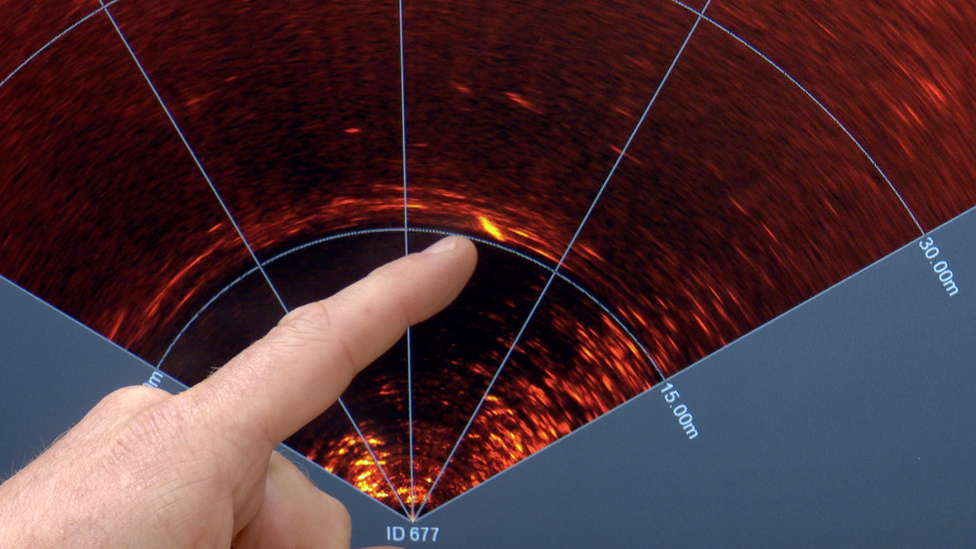

Firstly, sonar devices, that send out a very high frequency "ping" that seals can't hear but which builds up an image of their activities - imagine something out of an action movie but the orange shadow wiggling across the screen is a seal not jaws.

And secondly, hydrophones (underwater microphones), which listen out for creatures that make echolocation clicks - such as dolphins and porpoises - to work out what they're up to.

Finally, it has an "umbilical chord".

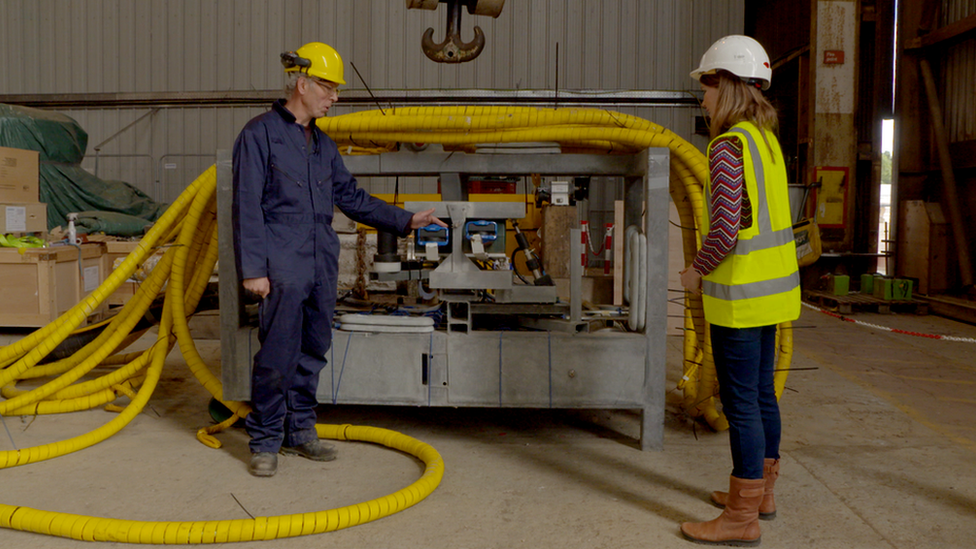

Dr Douglas Gillespie shows Harriet the sonar device that send out a very high frequency "ping"

Inside this steel-clad, thick and weighty yellow cable are optical fibres, which are actually about as thick as a human hair, that help bring the data ashore for analysis.

It's heavy enough to lie on the seafloor and doubles up as a power cable too.

Now no-one ever said this project - five years in the making and funded by the Scottish government, the Natural Environment Research Council and MeyGen - was going to be easy.

Some of the challenges faced highlight some of the reasons why tidal power is far behind wind in terms of development.

Think about it: salt water, strong currents, electrical equipment…

But where there's a will, there's a way, and after some test deployments, design changes and sorting out the power supply, this piece of kit has been sunk underwater and plugged in next to tidal turbines off the coast of John o' Groats.

The underwater turbines are huge

Where exactly? In the Pentland Firth, which boasts some of the strongest, fastest tidal currents in the world.

The "plugged-in" bit is crucial because this monitoring device has a constant power supply, meaning it's set to give long-term data.

Dr Douglas Gillespie, a senior research fellow at the Sea Mammal Research Unit at the University of St Andrews, says the industry can't develop without this "ground-breaking" data.

He told BBC Click: "This is really essential core knowledge for this industry.

"And if the government wants to license, large-scale tidal turbine developments, they absolutely are crying out for this knowledge so they can know what the environmental impact is going to be."

Dr Douglas Gillespie, Dr. Gordon Hastie and Fraser Johnson are part of the team behind the project

They have previously deployed equipment at this site in 2016, with data collected between 2017 and early 2020.

It showed porpoises visiting the site and the turbine every day but importantly when the rotors were on, these animals didn't actually swim through them, they went around them.

But there's a missing piece in the jigsaw puzzle.

The problem is the species of seals we have in the UK don't make very much noise underwater. So the only way to track them is through using active sonar, which is the new bit.

And this is essential when you think about the plight of harbour seals in this part of Scotland.

They were once known as the common seal, but that's just not reflective of their populations anymore.

The power of the sea in the Pentland Firth is both an opportunity and a challenge

Dr Gordon Hastie, a senior research fellow at the Sea Mammal Research Unit, says that about 20 years ago there would have been about 11,000 harbour seals in Orkney and the north coast of Scotland but 85% of the population has been lost.

It's not really fully known why but it could include changes in the prey, disease, biotoxin exposure, killer whale predation or competition with grey seals.

He says: "So there's a real conservation concern in terms of new industries being developed in areas that we want to minimise any potential impacts on these populations."

Dr Hastie says marine wildlife has an awful lot to lose from climate change and tidal energy is part of the drive towards green energy but it is also important to consider the potential impact on the local environment.

That's why industry is involved in this project.

The seals show up as an orange mark on the sonar

Fraser Johnson, the operations and maintenance manager of the Meygen Tidal Energy Project, is working with Dr Gillespie and Dr Hastie to get the data.

The MeyGen array currently has four turbines, the next step is to install potentially up to 40, but they need to know what the impact is on marine life.

Mr Johnson says tidal energy would be more predictable than wind.

"The wind doesn't always blow but tidal always keeps going and it's really that ability for us to keep the lights on," he says.

"I can tell you tomorrow right now, what's going to happen on site in a week, in a month, in 50 years' time. I can tell you how much we're going to produce. That predictability is where tidal really has its niche in the market."

Now installed, the team says the industry worldwide will be looking to learn from the data they gather this year because unlocking the secret lives of these creatures around turbines is needed to help industry move forward and for us to tackle climate change.

Related topics

- Published28 July 2021