Children's mental health care referrals up by 22% in Scotland

- Published

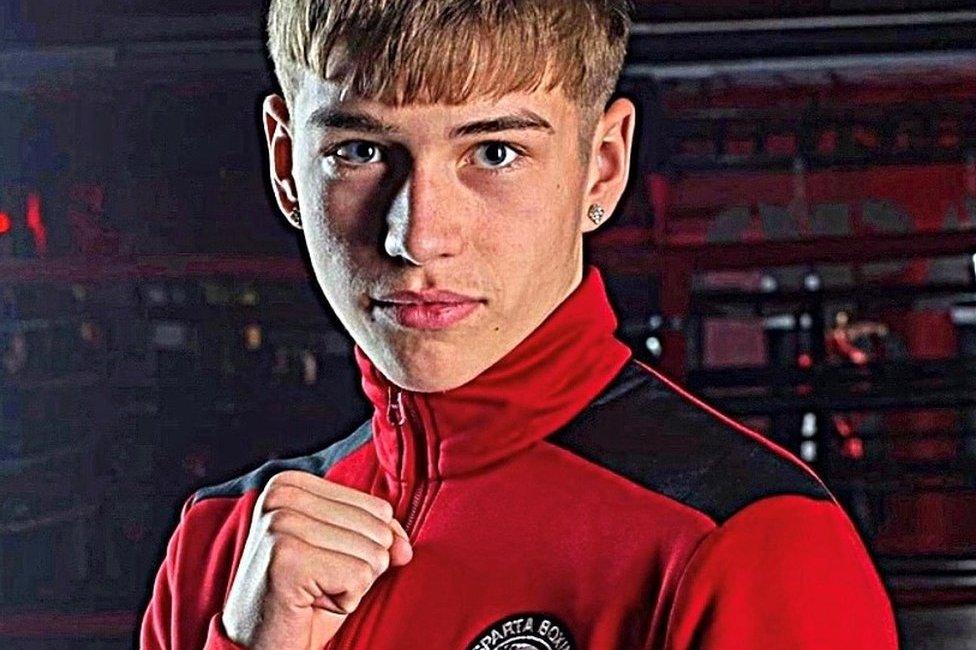

Shane Kay-Scott waited for 10 months for mental health care after being diagnosed with depression and social anxiety

The number of children being referred for mental health care in Scotland has risen by 22% since last year.

The latest Public Health Scotland (PHS) data, external shows 9,672 were referred to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) from January to March.

In that quarter, 73.2% were seen within 18 weeks - a slight increase from 72.7% during the same period last year.

The Scottish government said it was committed to its 18-week target for 90% of patients beginning treatment.

It has invested £40m to improve CAMHS and aims to clear all backlogs by March 2023.

The new figures show 9,672 children and young people were referred to CAMHS in Scotland between January and March 2022, compared to 10,021 for the previous quarter, and 7,902 for the same period in 2021.

A total of 5,016 began their treatment, an increase of 20.5% from the 4,162 starting treatment in the same quarter the previous year.

Half of the children and young people seen started their treatment within an average of nine weeks.

'It shouldn't be down to grieving families to put services in place'

Samantha Merrilees is worried about a potential increase in teen suicides over the next few years

Shane Kay-Scott, from Falkirk, was diagnosed with depression and social anxiety when he was 15.

It was 10 months between being referred to children and adolescent mental health services and getting treatment. During this time he tried to take his own life twice.

Speaking on BBC Radio's Good Morning Scotland programme, Shane, who is now 17, said: "My mental health didn't get any better during that 10 months. It did get a lot worse.

"It was really frustrating. It made me feel like no one cared and I wasn't important enough to get help and by the time they got round to seeing me I thought it was already too late."

He said he thought the government would "push a bit harder for the waiting times to be cut down" if they realised how much teenagers were suffering with mental health problems.

Shane eventually found support through the Scott Martin Foundation, external, which provided "amazing" therapy.

The foundation was set up by Samantha Merrilees, whose son Scott Martin killed himself after a long wait for mental health care.

The promising footballer and boxer was finally seen in December 2020 but by then his mental health had deteriorated. He died on 1 January 2021, aged 16.

Scott Martin was a promising footballer and boxer, but died at the age of 16

His mother told BBC Scotland she was worried there would be many more teen suicides over the next few years.

"Most charities that do the same stuff that we do have been started by parents or families that are grieving the loss of somebody," she said.

"It shouldn't be down to families that out of their grief put services like this in place.

"If you don't support them, then the only the thing that they've got, really, is to believe what they are thinking or experiencing and take their lives.

"I don't think that anybody should think that to take their own life is the best option that they've got, especially a child or young person."

The Scott Martin Foundation says it raises awareness of youth suicide and mental health, helps support young people suffering with poor mental health, and offers young people private counselling and therapies alongside boxing and exercise sessions.

It has helped more than 100 children in Falkirk since it was formed in 2021, many of them while they wait to be seen by designated mental health practitioners.

It also operates a "safe room" at the community centre in Hallglen where teenagers can go to talk to counsellors.

Kevin Stewart, Scotland's mental wellbeing minister, said government investment in CAMHS had been used to almost double the workforce and reduce the backlogs of waiting patients.

"Long waits for treatment are unacceptable," he said.

"We remain committed to meet the standard that 90% of patients begin treatment within 18 weeks of referral."

Mr Stewart added: "We have also provided an additional £15m to local authorities to deliver locally-based mental health and wellbeing support for five to 24-year-olds in their communities, providing alternative support options and ensured access to counselling support services in all secondary schools."

However, the Scottish Children's Services Coalition, external (SCSC), a group of private providers of specialist children's services, has warned of a mental health emergency for young people.

It has called for more investment in services as the impact of the pandemic on young people becomes clearer and the cost of living crisis pushes more people into poverty.

A spokesperson for SCSC said: "This is a crisis we can overcome, but as the country comes to terms with the biggest hit to its mental health in generations, it will require a similar energy and commitment to that demonstrated for Covid-19 if we are to achieve this and prevent many young people giving up on their futures."

These latest figures for Scotland echo what's happening in other parts of the UK.

More young people are needing help with their mental health - and not all of them are getting it as soon as they should.

Years of Covid restrictions and disrupted schooling are likely to be a big part of why we're seeing such rises in the number being referred.

But part of it could also be that society is becoming more aware of mental health and seeking help for it - and no group is more informed on this issue than young people.

The Scottish government says it is thanks to its investment in mental health services that the number of children and young people receiving treatment is at an "all-time high".

But families will agree that mental health services still need more support as many young people are still facing long waiting times - and suffering while they wait.

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this story, you can visit the BBC's Action Line.

- Published27 January 2022

- Published16 June 2021

- Published1 June 2021