Scotland has highest accidental drowning rate in UK

- Published

Accidental drownings last year rose to their highest level since 2015

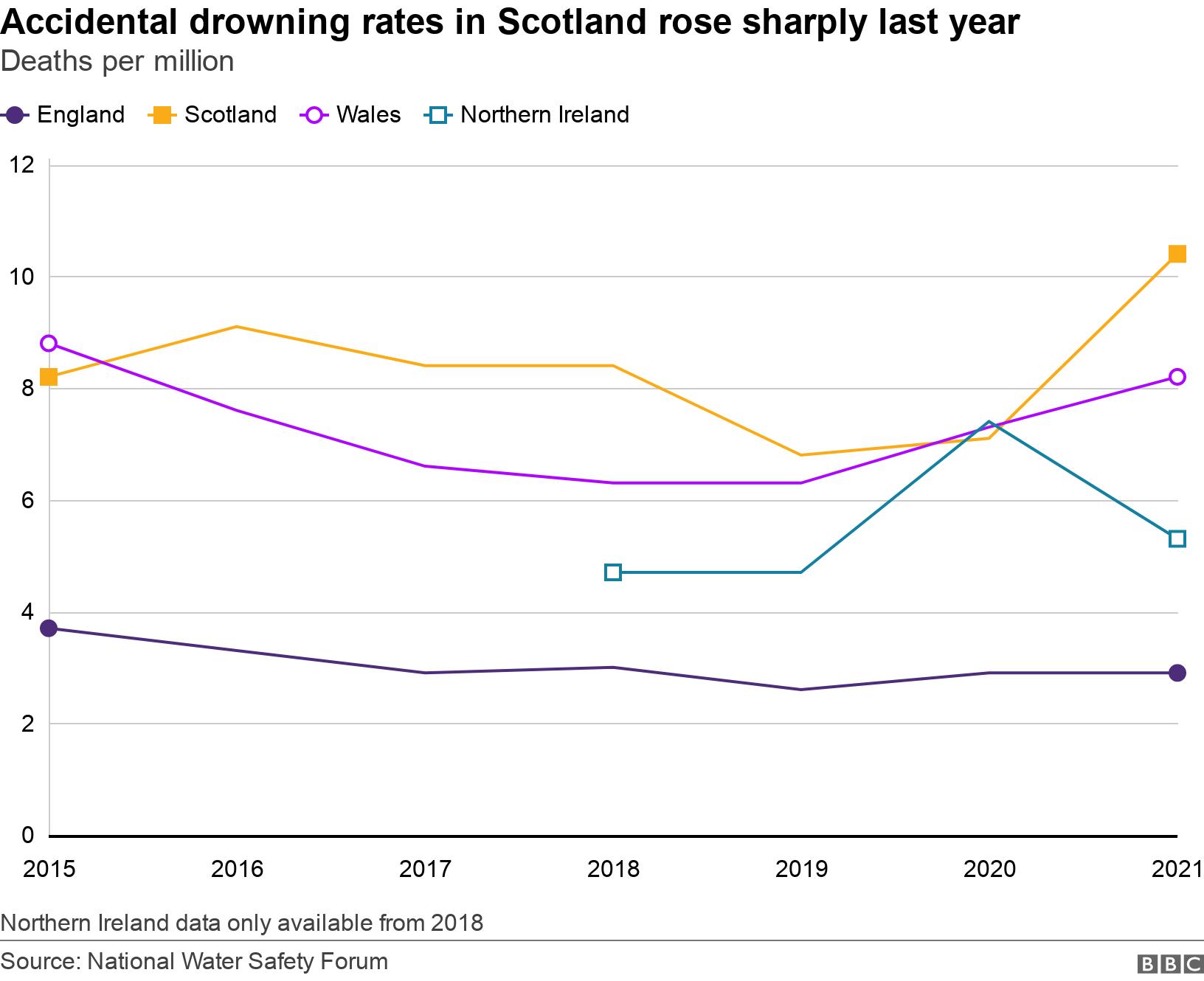

Scotland has the highest rate of accidental drowning of all the UK nations - despite a strategy to cut water deaths in half, figures show.

The plan to halve accidental drownings by 2026 was announced four years ago, but deaths last year rose to their highest level since 2015.

Scotland had a rate of 10 drownings per million people last year, more than three times the rate in England.

The Scottish government published a water safety action plan in March.

A spokesman said the plan was designed to support the 2018 drowning prevention strategy and included extra funding, updated signs and lesson plans for pupils.

Fifty-seven people accidentally drowned in Scotland last year and one person died of natural causes in the water. There were 39 accidental drownings in 2020.

In July 2021, seven people died after a weekend of incidents that rescue teams called the "worst in memory".

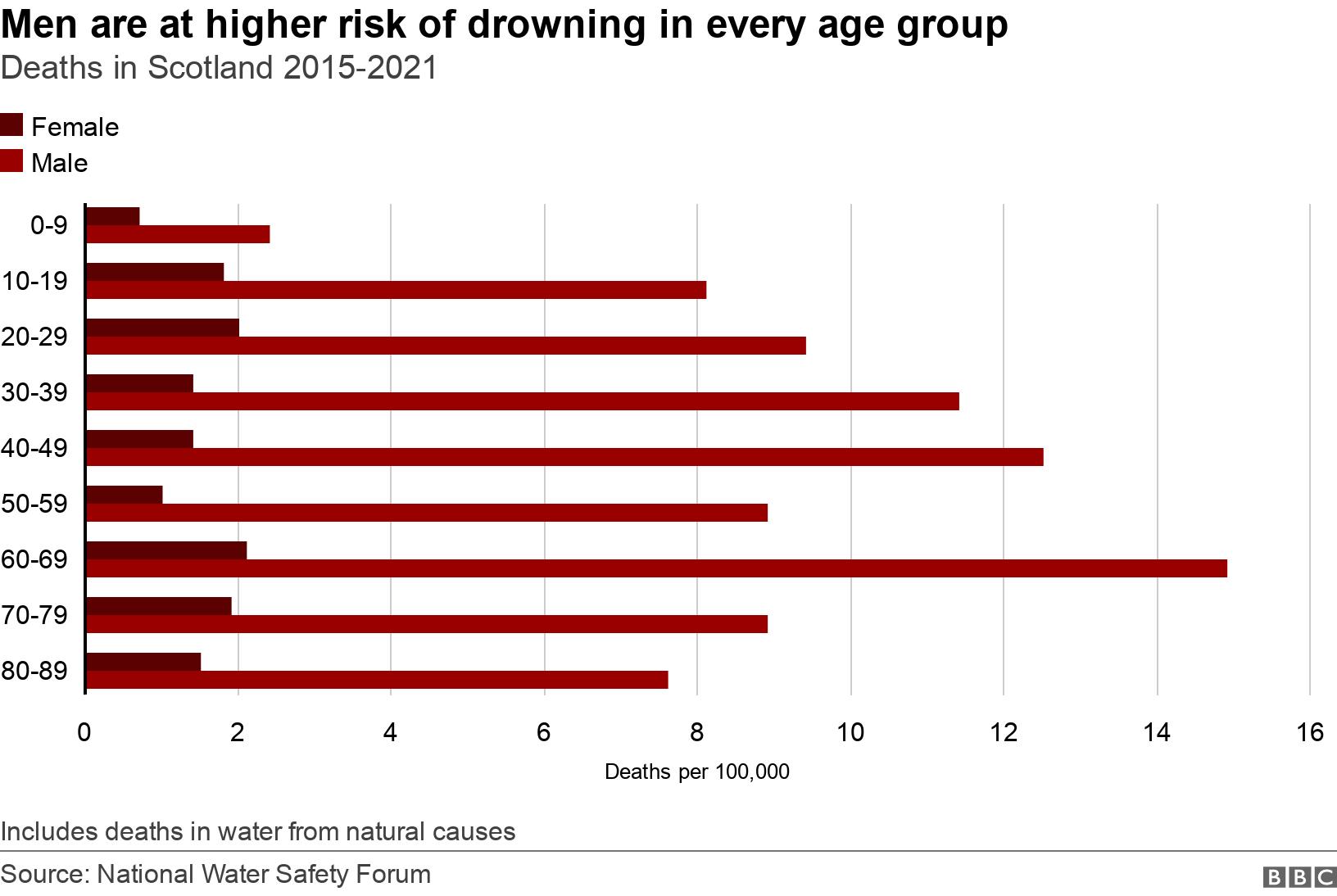

Scottish figures from the National Water Safety Forum covering 2015-2021 show the group most at risk of drowning are men in their 60s.

Studies indicate this is down to a combination of factors, including increased exposure to water and a higher level of risk taking among men.

Water safety experts believe that widespread access to lochs and rivers, along with colder water, contribute to the generally higher rates of drowning in Scotland.

Laura Erskine, the RNLI's water safety education manager, said: "We have beautiful scenery across Scotland that people should be able to enjoy, but sadly the access to water does come with negative by-products.

"People can get into trouble with cold water shock. Our waters can get extremely cold even on warm days."

The RNLI is one of 18 partners involved in the Scottish government's water safety plan, external.

Ms Erskine told BBC Scotland: "Unfortunately we have seen a rise in fatalities and water-related injuries. What I can say though is there's a collaborative determination to reduce those drownings."

Five things we know from the Scottish drowning figures

1. Men are far more likely to drown than women, even in the youngest age groups. Fewer than two in every 100,000 women accidentally drowned over the past seven years, compared with almost 10 men in every 100,000.

2. Risk tends to increase with age. It peaks with the 60-69 age group and then falls away again.

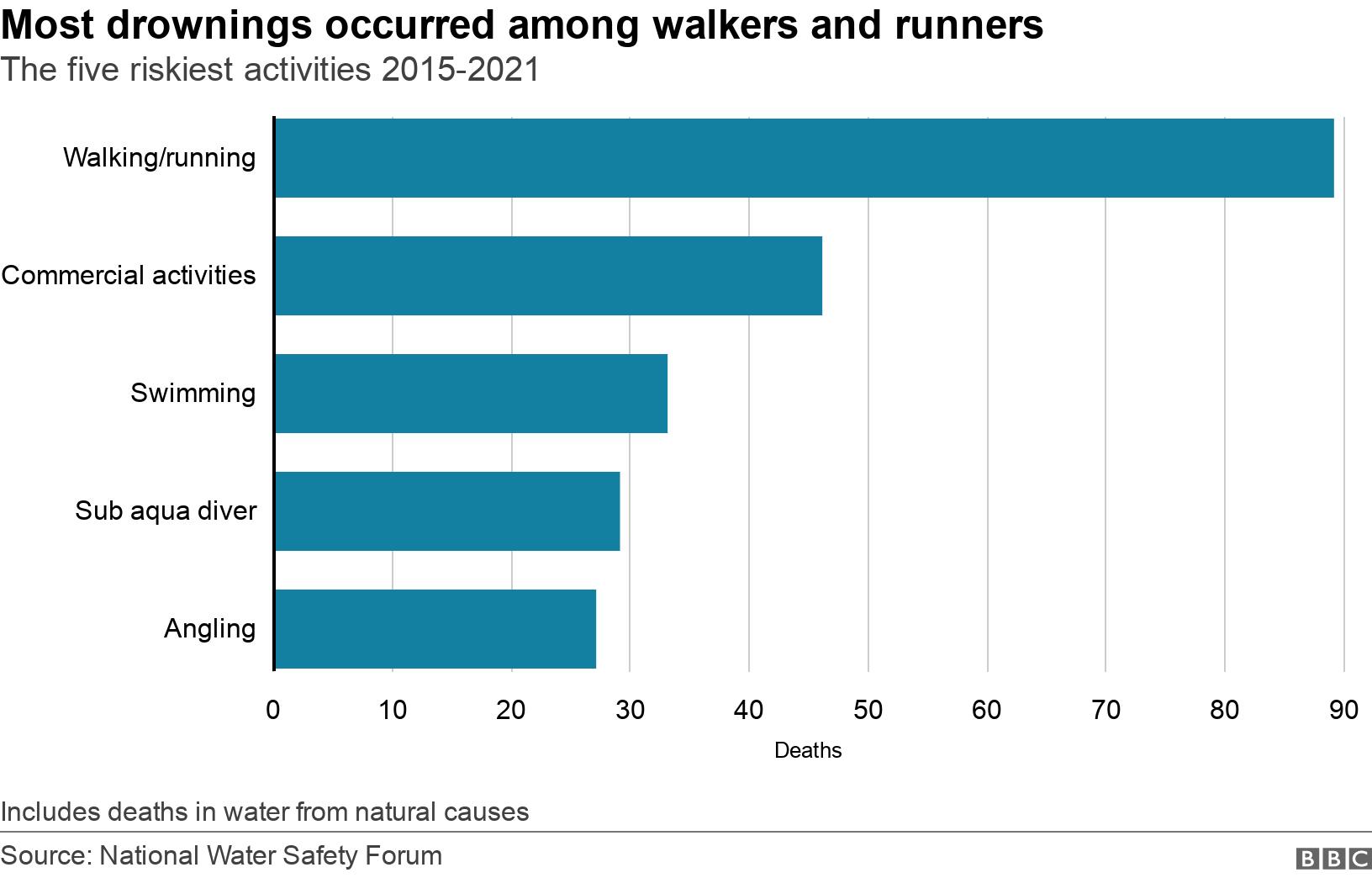

3. People who plan to go into the water are not necessarily at higher risk. Almost three times more walkers and runners drowned than swimmers.

4. More than half of all accidental drownings happen along the coast or in rivers. The next riskiest location is lochs.

5. Drownings are most common in July. Most deaths throughout the year occur on Saturdays.

Source: National Water Safety Forum, external 2015-2021 figures

'There's no better sight than a lifeboat steaming in your direction'

Simon Cole-Hamilton, from Inverness, went sailing in the Moray Firth on what appeared to be a calm day in June 2017.

The accountant set off with a friend from Chanonry Sailing Club at Fortrose, heading west towards the Kessock Bridge.

However, a storm hit them as they approached Avoch and their small dinghy capsized.

"A sudden squall came along and over we went," Mr Cole-Hamilton told the BBC.

"It's all topsy-turvy because you're thrown upside down. I went the direction the boat was turning in - head first into the water. Tim fell backwards into the wind so we ended up on opposite sides of the boat."

Mr Cole-Hamilton, who was then 66, was able to help his friend around to the leeward side of the boat and the pair managed to right the craft.

They got back into the boat with some difficulty, but they could not manoeuvre it or bail the water out fast enough as waves crashed over the side.

Simon Cole-Hamilton (second from right) and his friend Tim were rescued by the RNLI Kessock Lifeboat

"We both found ourselves sitting in a boat up to our waists in water," Mr Cole-Hamilton said. "I'm not quite sure how wide the Firth is - but it looks jolly wide when you're low in the water."

Mr Cole-Hamilton said his friend started to "shiver and shake" with the cold, so he decided to call for help. A Coastguard helicopter and the Kessock Lifeboat was sent to rescue them.

"The first thing to arrive was the helicopter and we could see it coming from the airport in our direction. First of all it missed us and it just shows how invisible you are when you're low in the water. There's not a lot to see in a stormy sea."

Once the helicopter spotted them, it helped guide in the lifeboat, which arrived in about 20 minutes.

"There's no better sight than seeing a rescue lifeboat coming steaming straight in your direction with the spray splashing out," he said.

The pair were airlifted to Raigmore Hospital in Inverness where they were treated for hypothermia.

Mr Cole-Hamilton said swimming to shore would probably have been impossible given the distance and rough seas.

"I didn't fancy our chances in either direction - so it was lucky that it didn't come down to that," he said.

"We've certainly learnt that we as sailors have got limitations and the boat has got limitations. It's very easy to move from scudding along in a most enjoyable way to the situation deteriorating and becoming something that's almost beyond your control."

The 'hidden epidemic' of drowning

Mr Cole-Hamilton was wearing a life jacket and had the skills to right his dinghy after it capsized. His story ended well - but he was in the highest risk group for drowning at the time of his accident.

The pattern of high drowning rates among older men in Scotland was highlighted in a 2018 report by The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents, external. It has also been observed in other countries around the globe.

A recent paper analysing accidental drownings in Australia, Canada and New Zealand, external found the proportion of deaths in all older adults had increased significantly, calling it a "hidden epidemic".

Other studies have suggested that the factors causing higher drowning rates in men, external include increased exposure to water, "riskier behaviour" and being more likely to be alone when swimming or boating.

What is cold water shock and why is it so dangerous?

Many of Scotland's lochs become extremely deep very close to the shore, as this aerial picture of Loch Lomond shows

Scotland's deep lochs and cold waters mean even strong, confident swimmers can drown.

Leigh Hamilton, ranger manager at The Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park, said one of the biggest risks was cold water shock.

"Your limbs stop moving properly and it's harder for your blood pressure to maintain the rhythm of your heart so it can cause a heart attack," she said.

"The sudden cooling of the skin means you're desperately gasping for breath because you start to panic. That makes you start to choke and the feeling of panic increases to the point where you're inhaling water directly into your body, which obviously can result in drowning.

"It's as quick as that, it's a severe as that and even the best swimmer in the world can be exposed to cold water shock."

Ms Hamilton said people who found themselves in this situation should float on their back in a star shape, external instead of trying to swim.

- Published13 June 2022

- Published13 August 2021

- Published30 July 2021